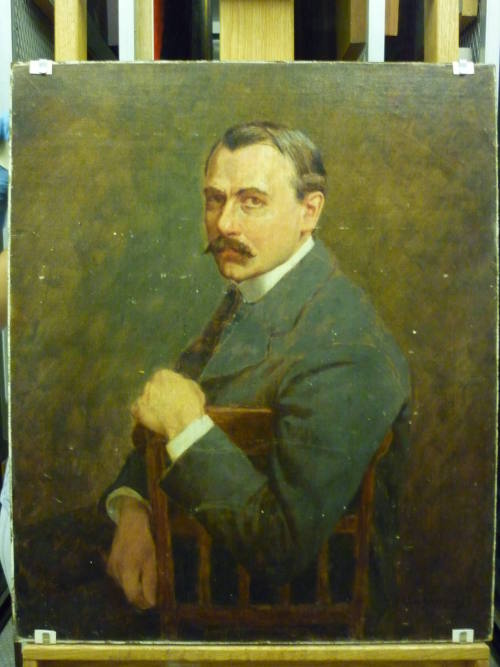

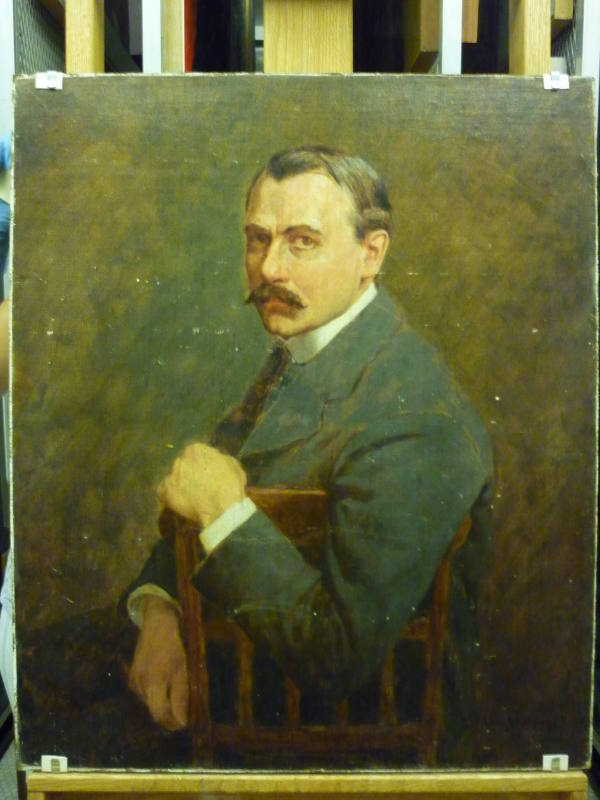

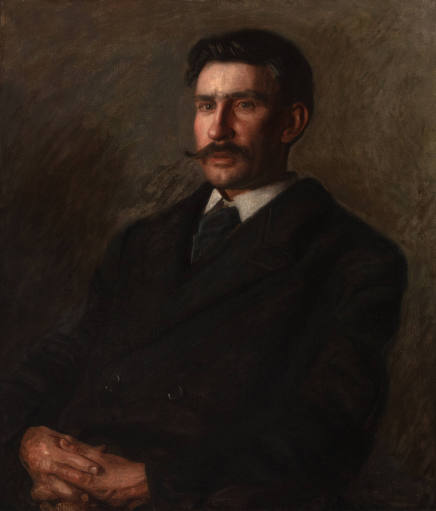

1861 - 1912

Born to a family of poor German immigrants in New York's lower East Side, Charles Scheyvogel worked as an office boy and newspaper seller while attending public school. After his parents moved to Hoboken, NJ, he found employ carving Meerschaum pipes, as a die sinker, and as of 1877, in the lithographic trade. He received the benefit of advice and instruction from H.A. Schwabe, a co-worker who taught at the Newark Art League. With financial support from friends and relatives, Schreyvogel went abroad in 1887, spending three years in Munich under Carl Marr and Johann F. Kirschbach.

After returning to New York, he continued his lithographic work, making largely unsuccessful attempts at painting portraits, landscapes, and miniatures. Schreyvogel had long been interested in the West, and in 1893 he made his first trip to Colorado and Arizona. Many sketches and artifacts were brought back to Hoboken, where he began producing detailed historical western scenes. Schreyvogel and his wife, Louise Walther, lived in relative obscurity and poverty until 1900, when his My Bunkie (Metropolitan Museum of Art) won the Academy's Clarke Prize. Schreyvogel, a virtual unknown, could not be located, and when press publicity alerted him to collect his prize, he had become an overnight sensation.

Schreyvogel's work is often compared to that of Frederic Remington, who attacked the former's Custer's Demand (Thomas Gilcrease Institute of History and Art, Tulsa, OK) on grounds of inaccuracy in 1903. Schreyvogel was vindicated, though, when Custer's widow and a former U.S. officer, Schuyler Crosby, wrote to the press in his defense. In 1905, he purchased a farm near West Kill, NY, and he continued to produce his well researched paintings until his death by blood poisoning.

After returning to New York, he continued his lithographic work, making largely unsuccessful attempts at painting portraits, landscapes, and miniatures. Schreyvogel had long been interested in the West, and in 1893 he made his first trip to Colorado and Arizona. Many sketches and artifacts were brought back to Hoboken, where he began producing detailed historical western scenes. Schreyvogel and his wife, Louise Walther, lived in relative obscurity and poverty until 1900, when his My Bunkie (Metropolitan Museum of Art) won the Academy's Clarke Prize. Schreyvogel, a virtual unknown, could not be located, and when press publicity alerted him to collect his prize, he had become an overnight sensation.

Schreyvogel's work is often compared to that of Frederic Remington, who attacked the former's Custer's Demand (Thomas Gilcrease Institute of History and Art, Tulsa, OK) on grounds of inaccuracy in 1903. Schreyvogel was vindicated, though, when Custer's widow and a former U.S. officer, Schuyler Crosby, wrote to the press in his defense. In 1905, he purchased a farm near West Kill, NY, and he continued to produce his well researched paintings until his death by blood poisoning.