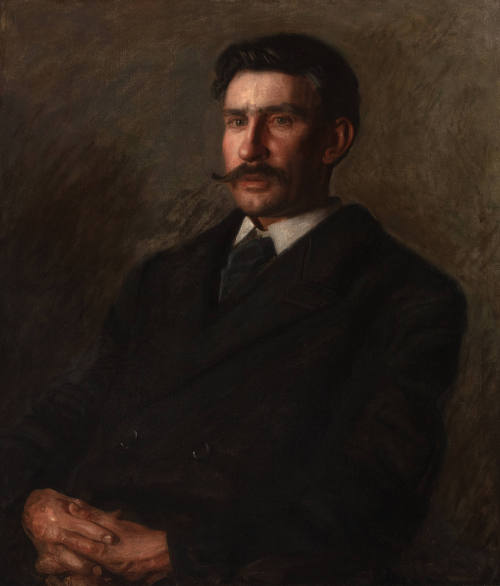

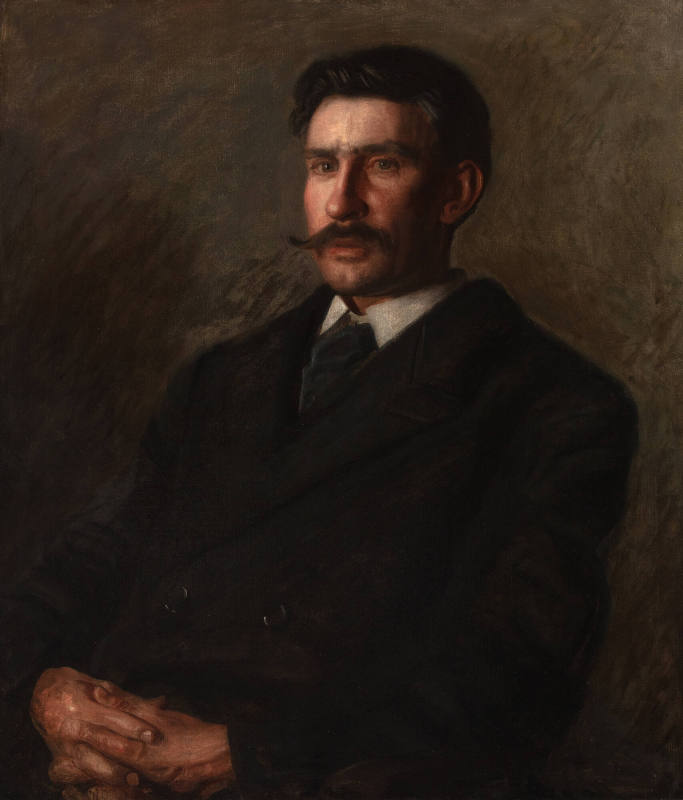

American, 1844 - 1916

Eakins attended Philadelphia's rigorous Central High School from 1857 to graduation in 1861; at the school he excelled in mathematics, sciences, French, and most significantly, drawing, which he studied all four years. For the next several years he worked with his father, a writing master and teacher of penmanship, while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1862 to 1866. For about the year 1864-65, he supplemented the Pennsylvania Academy's anatomy lectures with attendance at anatomy classes and demonstrations at Philadelphia's Jefferson Medical College.

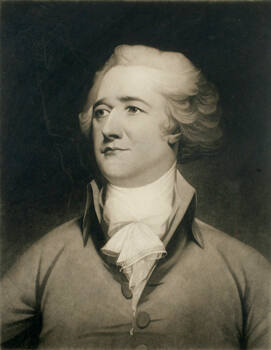

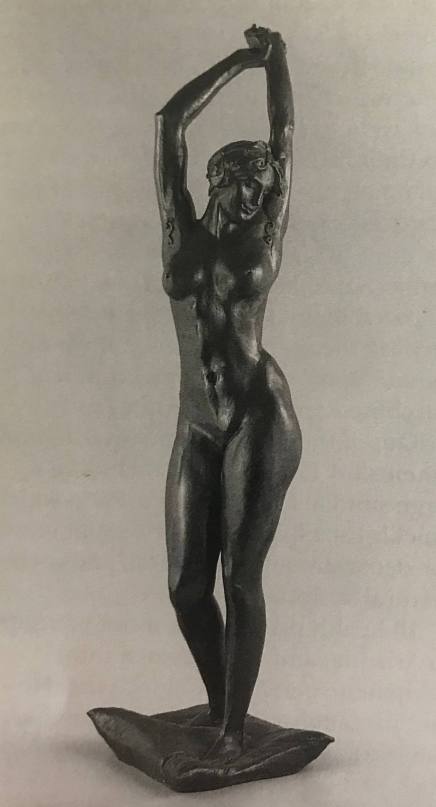

In the autumn of 1866, with that solid grounding in art study, Eakins went to Paris, where he was admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts to study under Jean-Léon Gérôme. The relationship between the highly distinguished French artist and his aspiring American student would remain warm. Excepting a Christmas visit home to Philadelphia in 1868, Eakins remained abroad studying and traveling into the summer of 1870. Besides his primary work with Gérôme, he also spent several months in the spring of 1868 studying clay modeling with Augustin Alexandre Dumont, and a year later worked briefly in the atelier of Léon Bonnat. Having felt he had attained all he could from formal instruction, Eakins passed the final six month of his European experience in Spain, chiefly in Seville, where he produced his first serious work.

Resettled permanently in the family home in Philadelphia--where he would reside all his life except for two years following his marriage in 1884 to Susan Macdowell--Eakins embarked on his career. That career would be marked in near-equal parts by rejection of his paintings and teaching methods by the majority of the artistic establishment, and the affection and respect of his students and a limited number of perceptive, progressive colleagues and patrons. He was uncompromising in the vision he transcribed in his art, and in his expectation that students exercise their full vision, in an era that valued idealization in its imagery and extreme modesty of conduct--even in artists' study of the figure. Eakins passed a lifetime of controversy with, and near-isolation from, his peers and public.

While Eakins came to rely on work as an instructor and lecturer as his principal source of income, he was a dedicated teacher. He first taught--without salary--evening drawing classes at the Philadelphia Sketch Club from 1874 to 1876. When the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts reopened in the autumn of 1876, after five years of building construction, he became the unpaid assistant to Christian Schussele, its professor of drawing and painting. In 1877, when dissident Pennsylvania Academy students formed the Philadelphia Art Student's Union, Eakins accompanied them as instructor. A year later, in the autumn of 1878, he returned to the Pennsylvania Academy as Assistant professor of painting and chief demonstrator of anatomy. At Schussele's death in August 1879, Eakins assumed his position and title, and at last received a salary. In 1882 he was appointed director of the Pennsylvania Academy School, the position from which he was forced to resign in February 1886, ostensibly because of his use of the entirely nude male model in life classes. His students promptly bolted the Pennsylvania Academy to form the Art Students League of Philadelphia, with Eakins as instructor; the League with Eakins's leadership, survived to 1893.

Simultaneously with his teaching in Philadelphia, Eakins had begun commuting to New York for appointments as lecturer on anatomy at several of the city's art schools. From 1881 through the school year 1884-85 he taught at the Students' Art Guild of the Brooklyn Art Association; in November 1885 he became the regular lecturer in anatomy at the Art Students League of New York, and continued through the 1888-89 season; that same 1888-89 year was his first as the National Academy's lecturer in anatomy; 1891-92 was the beginning of seven seasons as the lecturer in anatomy for the Woman's Art School of the Cooper Union.

Eakins gave his annual series of ten lectures at the National Academy beginning in 1888, and remained the Academy's lecturer on anatomy through 1894-95. During the 1893-94 season Eakins united the previously separated male and female classes, with some repercussions from students and press. Within the 1894-95 school year the chairman of the Council's school committee, and former fellow-student, Edwin Blashfield, had an informal and apparently amicable discussion with Eakins concerning some reservations the Academy had about his teaching methods. However, at the artist-managed Academy reaction was not as aggressive as it had been in Philadelphia; Eakins's contract was not renewed the next year, whether by mutual agreement, or one-sided decision is not recorded.

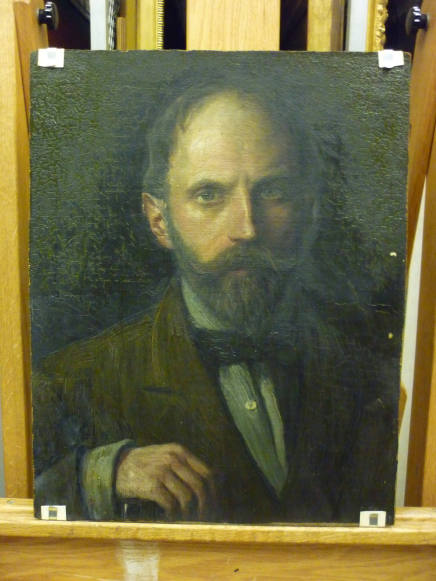

Eakins painted in watercolor in the earlier years of his career. He executed his first sculptures in 1883, and continued to work occasionally in sculpture through the mid-1890s; and from 1884 he was one of the most committed artist-photographers of the nineteenth century. However, painting in oil was his primary medium. He executed major subject pictures, such as scenes of scullers on the Schuylkill River, professional boxers, and sport hunters (where the central figures were generally specific person), but it was in portraiture that his expressive gift was most consistently and powerfully demonstrated.

For nearly twenty years from his first major opportunity to be introduced to a public, the Philadelphia Centennial exposition, when arguably his greatest work, The Gross Clinic, Portrait of Professor Gross, was rejected for display within the fair's art exhibition, Eakins was regularly thwarted in his efforts to have his work included in prestigious exhibitions. For much of that time his response was to withdraw from the conventional professional arena, concentrating on his work and on teaching. His paintings were fairly regularly seen in Pennsylvania Academy exhibitions to 1884, but only rarely over the next decade. Eakins was surprised and angered at the rejection of his first submission in 1875 for the National Academy annual, yet he tried again. His work was shown in the annuals of 1877 through 1879, 1881 and 1882. He exhibited with the progressive Society of American Artists from the year of its founding, 1878, into the mid-1880s; however, in 1892 he resigned from the Society, stating that its consistent rejection of his work for the exhibitions of the three previous years demonstrated an intolerable difference in standards.

Eleven Eakins paintings were included in the art exhibition of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He received a medal, the first since several of his watercolors had received an award in the 1878 Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics' Association exhibition in Boston. While the years following the Columbian Exposition hardly saw a blossoming of general enthusiasm for Eakins art, they were more receptive to the uncompromising realism and psychological penetration of his vision. Beginning in 1894 he again became a regular exhibitor at the Pennsylvania Academy. He participated in National Academy annuals in 1895 and 1896, 1902 and yearly from 1904 throughout his life, and in 1905 received the Academy's Proctor Prize for portraiture. His work was accepted for the first Carnegie Institute International, Pittsburgh, in 1896, and was seen regularly in Carnegie shows from 1899 through 1912; in addition he was frequently a member of the Carnegie jury. Among the awards he now received were medals in the Saint Louis world's fair of 1904, and the Pennsylvania Academy's Temple Gold Medal the same year. Ill health, including failing eyesight, curtailed his capacity to work for the last five years of his life.

In the autumn of 1866, with that solid grounding in art study, Eakins went to Paris, where he was admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts to study under Jean-Léon Gérôme. The relationship between the highly distinguished French artist and his aspiring American student would remain warm. Excepting a Christmas visit home to Philadelphia in 1868, Eakins remained abroad studying and traveling into the summer of 1870. Besides his primary work with Gérôme, he also spent several months in the spring of 1868 studying clay modeling with Augustin Alexandre Dumont, and a year later worked briefly in the atelier of Léon Bonnat. Having felt he had attained all he could from formal instruction, Eakins passed the final six month of his European experience in Spain, chiefly in Seville, where he produced his first serious work.

Resettled permanently in the family home in Philadelphia--where he would reside all his life except for two years following his marriage in 1884 to Susan Macdowell--Eakins embarked on his career. That career would be marked in near-equal parts by rejection of his paintings and teaching methods by the majority of the artistic establishment, and the affection and respect of his students and a limited number of perceptive, progressive colleagues and patrons. He was uncompromising in the vision he transcribed in his art, and in his expectation that students exercise their full vision, in an era that valued idealization in its imagery and extreme modesty of conduct--even in artists' study of the figure. Eakins passed a lifetime of controversy with, and near-isolation from, his peers and public.

While Eakins came to rely on work as an instructor and lecturer as his principal source of income, he was a dedicated teacher. He first taught--without salary--evening drawing classes at the Philadelphia Sketch Club from 1874 to 1876. When the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts reopened in the autumn of 1876, after five years of building construction, he became the unpaid assistant to Christian Schussele, its professor of drawing and painting. In 1877, when dissident Pennsylvania Academy students formed the Philadelphia Art Student's Union, Eakins accompanied them as instructor. A year later, in the autumn of 1878, he returned to the Pennsylvania Academy as Assistant professor of painting and chief demonstrator of anatomy. At Schussele's death in August 1879, Eakins assumed his position and title, and at last received a salary. In 1882 he was appointed director of the Pennsylvania Academy School, the position from which he was forced to resign in February 1886, ostensibly because of his use of the entirely nude male model in life classes. His students promptly bolted the Pennsylvania Academy to form the Art Students League of Philadelphia, with Eakins as instructor; the League with Eakins's leadership, survived to 1893.

Simultaneously with his teaching in Philadelphia, Eakins had begun commuting to New York for appointments as lecturer on anatomy at several of the city's art schools. From 1881 through the school year 1884-85 he taught at the Students' Art Guild of the Brooklyn Art Association; in November 1885 he became the regular lecturer in anatomy at the Art Students League of New York, and continued through the 1888-89 season; that same 1888-89 year was his first as the National Academy's lecturer in anatomy; 1891-92 was the beginning of seven seasons as the lecturer in anatomy for the Woman's Art School of the Cooper Union.

Eakins gave his annual series of ten lectures at the National Academy beginning in 1888, and remained the Academy's lecturer on anatomy through 1894-95. During the 1893-94 season Eakins united the previously separated male and female classes, with some repercussions from students and press. Within the 1894-95 school year the chairman of the Council's school committee, and former fellow-student, Edwin Blashfield, had an informal and apparently amicable discussion with Eakins concerning some reservations the Academy had about his teaching methods. However, at the artist-managed Academy reaction was not as aggressive as it had been in Philadelphia; Eakins's contract was not renewed the next year, whether by mutual agreement, or one-sided decision is not recorded.

Eakins painted in watercolor in the earlier years of his career. He executed his first sculptures in 1883, and continued to work occasionally in sculpture through the mid-1890s; and from 1884 he was one of the most committed artist-photographers of the nineteenth century. However, painting in oil was his primary medium. He executed major subject pictures, such as scenes of scullers on the Schuylkill River, professional boxers, and sport hunters (where the central figures were generally specific person), but it was in portraiture that his expressive gift was most consistently and powerfully demonstrated.

For nearly twenty years from his first major opportunity to be introduced to a public, the Philadelphia Centennial exposition, when arguably his greatest work, The Gross Clinic, Portrait of Professor Gross, was rejected for display within the fair's art exhibition, Eakins was regularly thwarted in his efforts to have his work included in prestigious exhibitions. For much of that time his response was to withdraw from the conventional professional arena, concentrating on his work and on teaching. His paintings were fairly regularly seen in Pennsylvania Academy exhibitions to 1884, but only rarely over the next decade. Eakins was surprised and angered at the rejection of his first submission in 1875 for the National Academy annual, yet he tried again. His work was shown in the annuals of 1877 through 1879, 1881 and 1882. He exhibited with the progressive Society of American Artists from the year of its founding, 1878, into the mid-1880s; however, in 1892 he resigned from the Society, stating that its consistent rejection of his work for the exhibitions of the three previous years demonstrated an intolerable difference in standards.

Eleven Eakins paintings were included in the art exhibition of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He received a medal, the first since several of his watercolors had received an award in the 1878 Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics' Association exhibition in Boston. While the years following the Columbian Exposition hardly saw a blossoming of general enthusiasm for Eakins art, they were more receptive to the uncompromising realism and psychological penetration of his vision. Beginning in 1894 he again became a regular exhibitor at the Pennsylvania Academy. He participated in National Academy annuals in 1895 and 1896, 1902 and yearly from 1904 throughout his life, and in 1905 received the Academy's Proctor Prize for portraiture. His work was accepted for the first Carnegie Institute International, Pittsburgh, in 1896, and was seen regularly in Carnegie shows from 1899 through 1912; in addition he was frequently a member of the Carnegie jury. Among the awards he now received were medals in the Saint Louis world's fair of 1904, and the Pennsylvania Academy's Temple Gold Medal the same year. Ill health, including failing eyesight, curtailed his capacity to work for the last five years of his life.