No Image Available

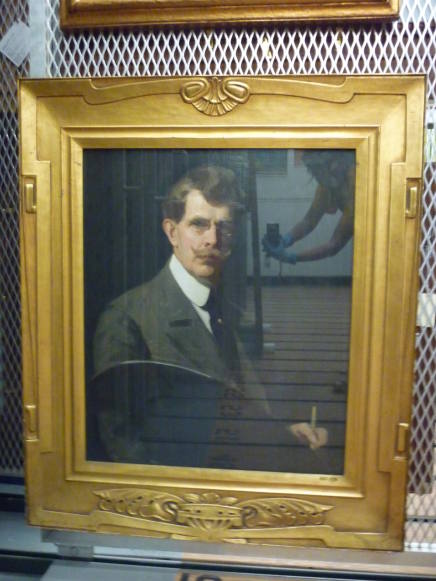

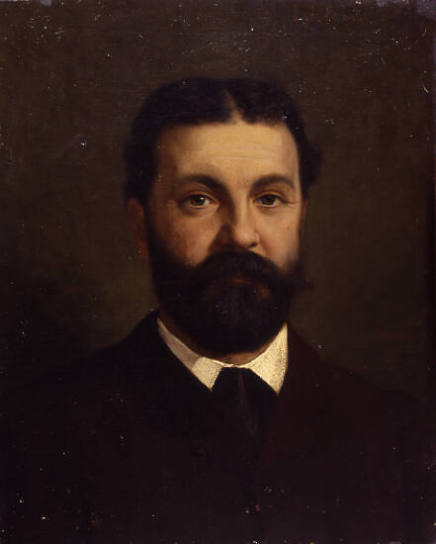

for George Fuller

American, 1822 - 1884

George Fuller is distinctive in having had two very different artistic characters, at two widely separated periods of his life. In the 1840s and 1850s his career followed the conventional pattern of an adequate painter of portraits. He then withdrew from the pursuit of an active career for fifteen years, during which time he evolved a highly individualistic, romantic mode of expression. Then, he returned to full participation in the American art community with canvases that made him a revered figure to the young, progressive painters of the day and a favorite of patrons.

Although he was born and reared on a country farm, Fuller was introduced early to the possibilities of art as a calling. Several of his mother's close relatives were practicing artists, and his half-brother, Augustus, was an itinerant portraitist. His father, intending that he have a business career, placed him first in a grocery and then in a shoe store, both in Boston-experiments that failed within a few months. Back in Deerfield he began sketching, an activity of which his mother disapproved and actively suppressed. At age fifteen he went with a party of railway surveyors to Illinois, a journey that occupied two years. For a time he contemplated a career as an engineer and spent about a year and a half completing his education at the Deerfield Academy. But in 1841 he commenced a professional career in art when he accompanied Augustus on a circuit of towns in western New York State, painting portraits. His professional career in art had begun.

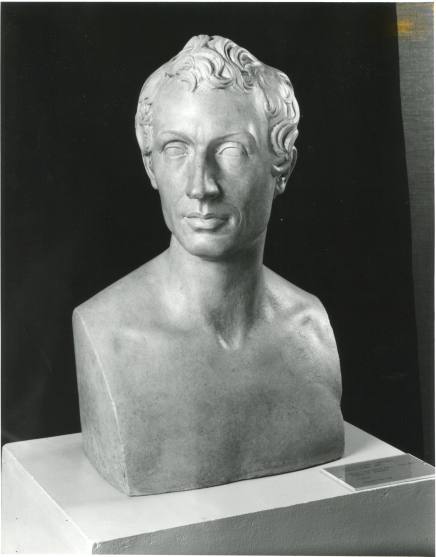

Late that year Fuller applied to the sculptor Henry Kirke Brown-a friend from the Deerfield area, who was then established in Albany-for advice on his future as a painter. Brown's response was warmly encouraging, and in the winter of 1842 Fuller joined Brown in Albany. He studied with Brown for nine months, returning to Deerfield in October, shortly after the sculptor left for Europe. (Fuller's portrait of Brown, shown in the Academy annual of 1856, was the work that garnered him the highest critical praise he received during the first phase of his career. It would erroneously, and repeatedly, be cited as the work that secured his election to Academy membership.)

Early in 1842 he moved to Boston, and in August 1843 he sent Brown what proved to be a prophetic account of his reactions to his first season as an aspiring artist (quoted in William Dean Howells, "Sketch of George Fuller's Life," in George Fuller: His Life and Works, 1886, 17):

[block quote:]

Joined the Artists' Association, and improved the evenings last winter drawing from nature, such as we could find, and casts. Their second exhibition opens September 1st. The Athenaeum this year is very fine; the best pictures by our painters are Allston's, Stuart's, and Huntington's. I think the best picture in the room is Allston's Saul and the Witch. It is the only specimen I have ever seen of that great man. You will be grieved to hear he is dead. This took place about three weeks since. . . . The greatest of modern painters is gone, and on whom does his mantle fall? . . .

When I first came to B[oston], I was dazzled by this and attracted by that; I imagined I found many things worthy [of] my study and imitation. I have got over this, and have concluded to see nature for myself, through the eye of no one else, and put my trust in God, awaiting the result.

[end of block quote]

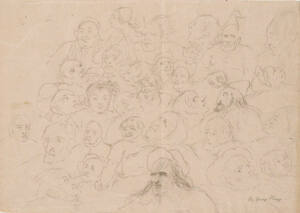

Fuller remained based in Boston, making portrait-painting expeditions into western Massachusetts and New York State, until late in 1847, when at the urging of Brown, who was now settled in New York, he moved to that city. In the autumn of 1848 he entered the Academy school's antique class, and at the turn of the new year he was admitted to the life class. A few months later he was represented in an Academy annual exhibition for the first time. Over the next decade Fuller barely sustained a living as a portraitist in New York. During this period, apart from three winter visits to the South when he did a number of drawings focused on the lives of African Americans, nearly all his works were straightforwardly rendered portraits. He showed these in each Academy annual from 1852 through 1857. In the annual of 1860, however, he was represented by a painting entitled After the Bath-suggesting the start of a move toward more imaginative art.

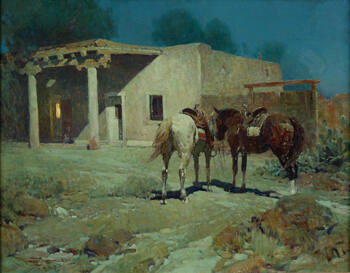

By the time the 1860 annual opened in mid-April, Fuller had been in Europe for three months. He did not return until that August, having intently studied the work of the Old Masters and contemporary artists in the major cities of England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, and Belgium. His father had died in June 1859, and Fuller made this tour preparatory to committing himself to the year-round responsibility of maintaining the family home and farm. He returned to Deerfield willingly, as he was strongly attached to his home and its surrounding landscape. For the next fifteen years Fuller worked hard and successfully as a farmer. He did not, however, abandon his painting. He set up a studio, working on Sundays and in the winters. He developed paintings from sketches he had made in Europe and from the local landscape. The figures that often were the focal point of his compositions were based on members of his family. In this isolation his always poetic, imaginative response to nature was given full rein. Along with his unique vision he developed an idiosyncratic technique that gave his canvases a mood-evoking glow. Fuller's work was occasionally exhibited during this period, including two paintings shown in the 1868 Academy annual.

Despite Fuller's best efforts, his farm went bankrupt, as did many of his neighbors', in a general failure of prices in 1875. He again turned to art as a potential means of livelihood and set about reestablishing his professional standing. Taking a selection of his work to the Doll and Richard's gallery in Boston in 1876, he found a favorable response and was given an exhibition. The show was a critical and financial success. He moved to Boston, where he continued producing his highly individualistic landscape, figure, and subject paintings for the remaining eight years of his life.

Boston was especially receptive to Fuller's art. The city's other leading art-world figure of the time was William Morris Hunt, who had introduced the work of the French Barbizon painters to major Boston patrons. Hunt's own work and Fuller's, while not essentially similar, had an affinity in their subjective response to nature. The two artists formed a friendship that lasted until Hunt's death in 1879. Washington Allston's mantle had clearly passed to these men. Although Fuller took no students, he had a pervasive influence on a number of the city's rising younger painters of the 1870s, thus passing on the Boston tradition of romanticism.

Boston was not Fuller's only appreciative audience. The newly founded Society of American Artists in New York responded with notable warmth to his work. Fuller showed in every Society exhibition from its first, in 1878, through that of 1883; he was elected a member in 1880. He also returned to exhibiting in Academy annuals in 1878 and was represented in each one through 1881. The works that appeared at the Academy, such as Turkey Pasture (shown in 1878), Quadroon (in 1880), and Winefred Dysart (in 1881), tended to be those that attracted the most attention in the press and in the memories of critics writing about him in later years. Yet despite the acclaim he was now receiving, he was not elected to full Academy membership. This may be accountable to his being championed by the Society of American Artists and to the tensions between the two organizations in the Society's first years. It may be understandable that the Academy could not endorse Fuller's denial of the discipline of academic principles in just the years the organization was fighting to maintain their supremacy. Nonetheless, the Academy gave Fuller a warm and extensive tribute in its 1884 accounting of members who had died during the previous year. Included was a lengthy review of his career, in which it was noted that his submissions to the later annuals "were of such increased excellence as to win the admiration of the Art world, and to raise him at once to the high rank he justly held." The tribute concluded, "Mr. Fuller's personal character commended him to the esteem of his fellow men and won the love of his friends, and in his death the world has lost a good man and a most admirable artist."

Although he was born and reared on a country farm, Fuller was introduced early to the possibilities of art as a calling. Several of his mother's close relatives were practicing artists, and his half-brother, Augustus, was an itinerant portraitist. His father, intending that he have a business career, placed him first in a grocery and then in a shoe store, both in Boston-experiments that failed within a few months. Back in Deerfield he began sketching, an activity of which his mother disapproved and actively suppressed. At age fifteen he went with a party of railway surveyors to Illinois, a journey that occupied two years. For a time he contemplated a career as an engineer and spent about a year and a half completing his education at the Deerfield Academy. But in 1841 he commenced a professional career in art when he accompanied Augustus on a circuit of towns in western New York State, painting portraits. His professional career in art had begun.

Late that year Fuller applied to the sculptor Henry Kirke Brown-a friend from the Deerfield area, who was then established in Albany-for advice on his future as a painter. Brown's response was warmly encouraging, and in the winter of 1842 Fuller joined Brown in Albany. He studied with Brown for nine months, returning to Deerfield in October, shortly after the sculptor left for Europe. (Fuller's portrait of Brown, shown in the Academy annual of 1856, was the work that garnered him the highest critical praise he received during the first phase of his career. It would erroneously, and repeatedly, be cited as the work that secured his election to Academy membership.)

Early in 1842 he moved to Boston, and in August 1843 he sent Brown what proved to be a prophetic account of his reactions to his first season as an aspiring artist (quoted in William Dean Howells, "Sketch of George Fuller's Life," in George Fuller: His Life and Works, 1886, 17):

[block quote:]

Joined the Artists' Association, and improved the evenings last winter drawing from nature, such as we could find, and casts. Their second exhibition opens September 1st. The Athenaeum this year is very fine; the best pictures by our painters are Allston's, Stuart's, and Huntington's. I think the best picture in the room is Allston's Saul and the Witch. It is the only specimen I have ever seen of that great man. You will be grieved to hear he is dead. This took place about three weeks since. . . . The greatest of modern painters is gone, and on whom does his mantle fall? . . .

When I first came to B[oston], I was dazzled by this and attracted by that; I imagined I found many things worthy [of] my study and imitation. I have got over this, and have concluded to see nature for myself, through the eye of no one else, and put my trust in God, awaiting the result.

[end of block quote]

Fuller remained based in Boston, making portrait-painting expeditions into western Massachusetts and New York State, until late in 1847, when at the urging of Brown, who was now settled in New York, he moved to that city. In the autumn of 1848 he entered the Academy school's antique class, and at the turn of the new year he was admitted to the life class. A few months later he was represented in an Academy annual exhibition for the first time. Over the next decade Fuller barely sustained a living as a portraitist in New York. During this period, apart from three winter visits to the South when he did a number of drawings focused on the lives of African Americans, nearly all his works were straightforwardly rendered portraits. He showed these in each Academy annual from 1852 through 1857. In the annual of 1860, however, he was represented by a painting entitled After the Bath-suggesting the start of a move toward more imaginative art.

By the time the 1860 annual opened in mid-April, Fuller had been in Europe for three months. He did not return until that August, having intently studied the work of the Old Masters and contemporary artists in the major cities of England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, and Belgium. His father had died in June 1859, and Fuller made this tour preparatory to committing himself to the year-round responsibility of maintaining the family home and farm. He returned to Deerfield willingly, as he was strongly attached to his home and its surrounding landscape. For the next fifteen years Fuller worked hard and successfully as a farmer. He did not, however, abandon his painting. He set up a studio, working on Sundays and in the winters. He developed paintings from sketches he had made in Europe and from the local landscape. The figures that often were the focal point of his compositions were based on members of his family. In this isolation his always poetic, imaginative response to nature was given full rein. Along with his unique vision he developed an idiosyncratic technique that gave his canvases a mood-evoking glow. Fuller's work was occasionally exhibited during this period, including two paintings shown in the 1868 Academy annual.

Despite Fuller's best efforts, his farm went bankrupt, as did many of his neighbors', in a general failure of prices in 1875. He again turned to art as a potential means of livelihood and set about reestablishing his professional standing. Taking a selection of his work to the Doll and Richard's gallery in Boston in 1876, he found a favorable response and was given an exhibition. The show was a critical and financial success. He moved to Boston, where he continued producing his highly individualistic landscape, figure, and subject paintings for the remaining eight years of his life.

Boston was especially receptive to Fuller's art. The city's other leading art-world figure of the time was William Morris Hunt, who had introduced the work of the French Barbizon painters to major Boston patrons. Hunt's own work and Fuller's, while not essentially similar, had an affinity in their subjective response to nature. The two artists formed a friendship that lasted until Hunt's death in 1879. Washington Allston's mantle had clearly passed to these men. Although Fuller took no students, he had a pervasive influence on a number of the city's rising younger painters of the 1870s, thus passing on the Boston tradition of romanticism.

Boston was not Fuller's only appreciative audience. The newly founded Society of American Artists in New York responded with notable warmth to his work. Fuller showed in every Society exhibition from its first, in 1878, through that of 1883; he was elected a member in 1880. He also returned to exhibiting in Academy annuals in 1878 and was represented in each one through 1881. The works that appeared at the Academy, such as Turkey Pasture (shown in 1878), Quadroon (in 1880), and Winefred Dysart (in 1881), tended to be those that attracted the most attention in the press and in the memories of critics writing about him in later years. Yet despite the acclaim he was now receiving, he was not elected to full Academy membership. This may be accountable to his being championed by the Society of American Artists and to the tensions between the two organizations in the Society's first years. It may be understandable that the Academy could not endorse Fuller's denial of the discipline of academic principles in just the years the organization was fighting to maintain their supremacy. Nonetheless, the Academy gave Fuller a warm and extensive tribute in its 1884 accounting of members who had died during the previous year. Included was a lengthy review of his career, in which it was noted that his submissions to the later annuals "were of such increased excellence as to win the admiration of the Art world, and to raise him at once to the high rank he justly held." The tribute concluded, "Mr. Fuller's personal character commended him to the esteem of his fellow men and won the love of his friends, and in his death the world has lost a good man and a most admirable artist."