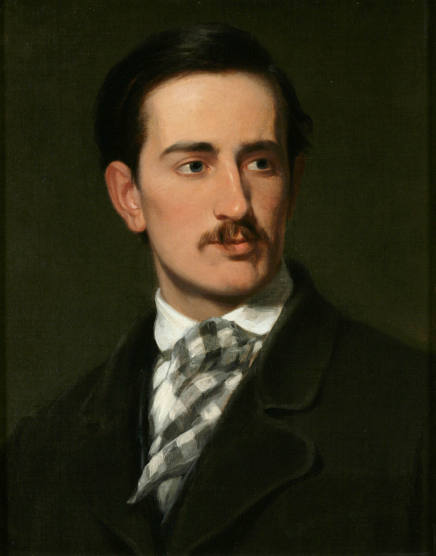

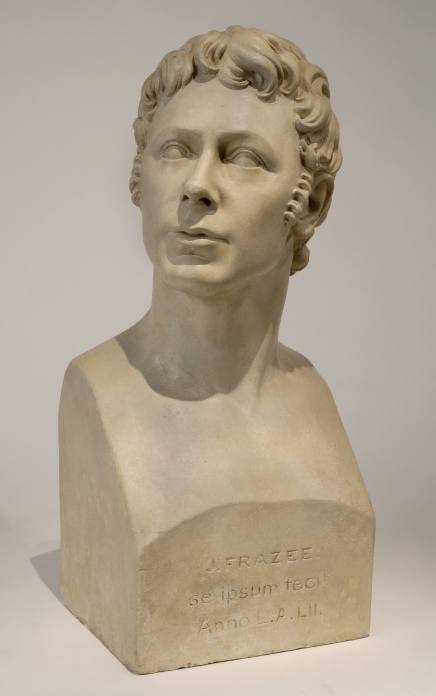

American, 1805 - 1852

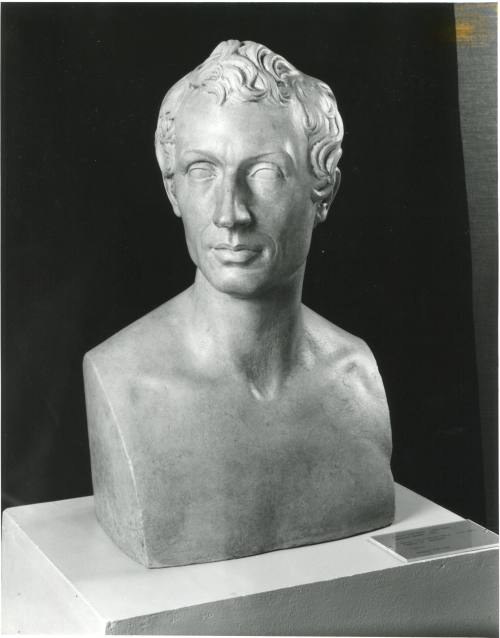

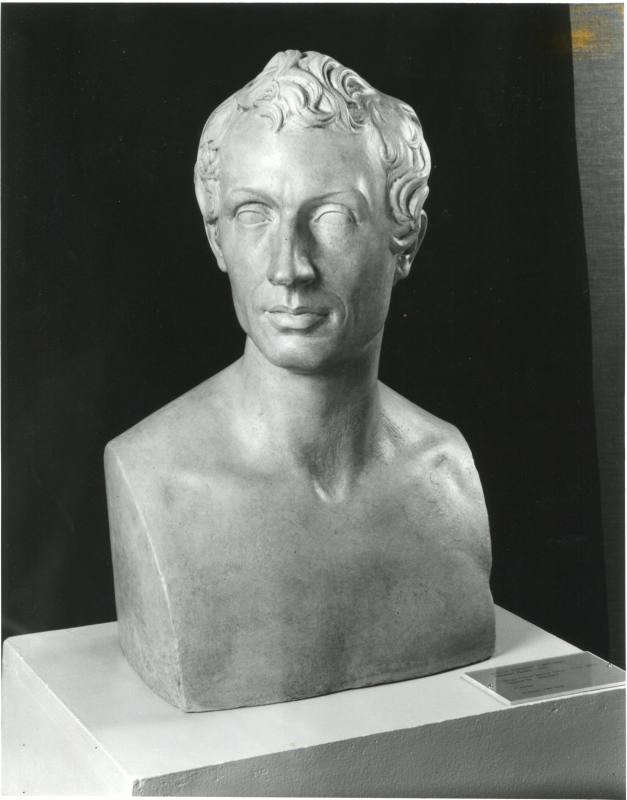

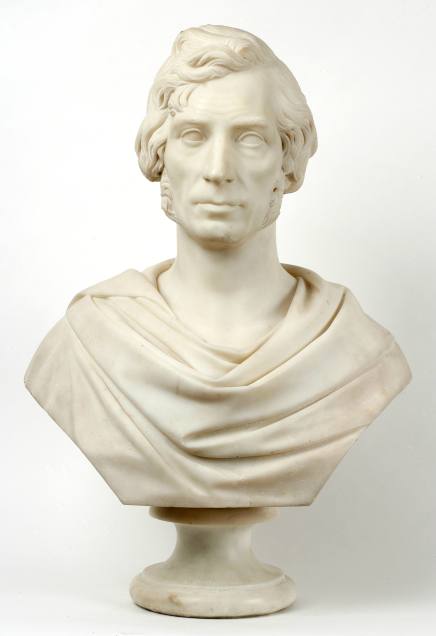

Although John Frazee was the first American to conceive and execute sculptural forms independent of functional or decorative motivation, Horatio Greenough was the first American sculptor to enter the international mainstream of Western cultural aspirations.

Greenough was early given access to the Boston Athenaeum's cast collection, but his practical training began under the Boston carvers Solomon Willard, who taught him to work in clay, and Alpheus Cary, who taught him to cut marble. Then, when he was about fifteen, he received instruction in modeling from J. B. Binion, a French sculptor who was living in Boston. A traditional education at Harvard College coupled with a friendship with Washington Allston introduced Greenough to the precepts of neoclassicism, which, joined with a respect for truth to nature, influenced his sculptural style.

In 1825 Greenough went to Rome, where he remained for two years until illness forced his return to the America. He spent some time in New York, Philadelphia, and finally Washington, D.C., before going again to Italy in 1828. He settled this time in Florence, where he came under the tutelage of Lorenzo Bartolini. There, late that year, he met James Fenimore Cooper, who quickly became not only a warm and generous friend but also a powerful influence on his career. It was Cooper who commissioned the group The Chanting Cherubs (unlocated), the piece that allowed Greenough to demonstrate his capacities in imaginative, ideal forms to an American audience. Completed in 1830, Cherubs was shipped to Boston the next year. Its public exhibition gained the sculptor some acclaim but little financial reward.

After Boston, Cherubs was shown in New York. Samuel F. B. Morse, then president of the National Academy, evidently let it be known that he was not pleased that the exhibition site arranged for by Greenough's brother was at the rival American Academy of Fine Arts. "You will I am sure, do me the justice to believe that had I been aware of it I should have countermanded the arrangement," Greenough wrote apologetically to Morse on January 5, 1832. "If those gen[tleme]n imagine that I am to be bamboozled into an approval of their association for the discouragement of art they will soon find their error" (quoted in Wright 1972, p. 102). Cherubs was seen again in New York, in the spring of 1832, when it marked Greenough's debut in an Academy annual exhibition.

Until he received the opportunity to sculpt the Chanting Cherubs group, Greenough had mainly produced portrait busts. But after demonstrating through that work his ability to create forms that were structurally and intellectually more complicated, other major commissions came to him. His first life-size marble, a recumbent Medora (1831-33, Baltimore Museum of Art), was executed for the distinguished Baltimore collector Robert Gilmor. Greenough's most significant commission came from the United States Congress, which in 1832 ordered a monumental image of George Washington (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.), intended for installation in the rotunda of the Capitol. This sculpture, on which he worked from 1832 until 1841, met with such a barrage of criticism-primarily for casting Washington in the role of Zeus, classically draped and bare-chested-that it was soon removed from the rotunda. Another major federal commission was The Rescue (1837-51), for the east front of the U.S. Capitol (U.S. Capitol, storage).

Greenough also made an indispensable contribution to American architectural theory with his well-known writings on form and function. The historian Nathalia Wright has called these "the first full and coherent public statement of the functional theory of architecture to be made by an American" (Wright 1963, p. 183).

Late in 1851 Greenough and his family gave up the expatriate life and returned to the Boston area. The next year he traveled frequently to Washington and New York in connection with his major projects, The Rescue and plans for an equestrian figure of George Washington for New York's Union Square, a work later completed by Henry Kirke Brown. Greenough suffered from a malady of the brain, and his condition, which had been deteriorating for a time, worsened during 1852. He died at the end of the year.

Because he lived abroad for so long, Greenough's association with the Academy was not as active as it might have been. He was an ardent supporter of the institution, as seen in his above-quoted letter to Morse, and a friend of a number of its leading members. He attended the Academy's antique classes during his stays in New York in 1827 and 1828 and held the appointment of the Academy's professor of sculpture from 1829 through 1836, although he was hardly available to perform instructional duties. His work was represented in Academy annuals from 1832 through 1835 and several times in the 1840s.

In appreciation of his election to honorary membership, Greenough wrote Morse in May 1828, offering a copy of the head of the Apollo Belvedere, which he had brought to America from Rome and which he "thought might be useful in your gallery" (Wright 1972, p. 11). Evidently Morse never availed himself of the offer, and the Apollo was probably that bust still in the possession of Mrs. Greenough in 1864, when it was shown at the Boston Athenaeum. A February 25, 1832, from a Leghorn, Italy, shipping agent to Academy secretary John L. Morton notes that Greenough directed the sending of "a Case of Pictures intended . . . for your National Academy . . . on board the Barque Prudent." No record of the contents of this case has surfaced, nor is its receipt noted in Academy minutes or evident in the collection. Greenough wrote Morton in March 1832 that he had "hopes of procuring several drawings by eminent artists for our academy." But again, it is not certain whether this beneficent attempt at acquisition was fulfilled (Wright 1972, p. 117).

Greenough's ambitions as a neoclassical sculptor and his attainments in the field, together with his support of the fledgling Academy, no doubt endeared him to its members. At Greenough's death, Asher B. Durand, in a eulogy written on behalf of the Council, expressed this esteem and took the opportunity to endorse the principle of cultural nationalism:

[block quote:]

Mr. Greenough may be justly regarded as the Father of American Sculpture. He has been taken from us in the prime of life, soon after his return from a foreign residence, to pursue his art at home.

Although his years have been spent abroad where he has earned a most distinguished fame, his great works adorn his own country and will descend to posterity among the noblest illustrations of her history. Greenough has done much towards the establishment of an American School of art and there are others, thank heaven, who still live alike entitled to our gratitude for their services in the noble cause. Who while they acknowledge the advantage of study in foreign schools to complete, so to speak, their art education, choose not to surrender their identity and pass away in the current of servile imitation. This is as it should be. Our National importance and power, our history and our scenery, exert a united influence which unimpeded by conventional schools, cannot fail to produce an original School of Art worthy to share the tribute of universal respect already paid to our condition of political advancement.

[end of block quote]

Greenough was early given access to the Boston Athenaeum's cast collection, but his practical training began under the Boston carvers Solomon Willard, who taught him to work in clay, and Alpheus Cary, who taught him to cut marble. Then, when he was about fifteen, he received instruction in modeling from J. B. Binion, a French sculptor who was living in Boston. A traditional education at Harvard College coupled with a friendship with Washington Allston introduced Greenough to the precepts of neoclassicism, which, joined with a respect for truth to nature, influenced his sculptural style.

In 1825 Greenough went to Rome, where he remained for two years until illness forced his return to the America. He spent some time in New York, Philadelphia, and finally Washington, D.C., before going again to Italy in 1828. He settled this time in Florence, where he came under the tutelage of Lorenzo Bartolini. There, late that year, he met James Fenimore Cooper, who quickly became not only a warm and generous friend but also a powerful influence on his career. It was Cooper who commissioned the group The Chanting Cherubs (unlocated), the piece that allowed Greenough to demonstrate his capacities in imaginative, ideal forms to an American audience. Completed in 1830, Cherubs was shipped to Boston the next year. Its public exhibition gained the sculptor some acclaim but little financial reward.

After Boston, Cherubs was shown in New York. Samuel F. B. Morse, then president of the National Academy, evidently let it be known that he was not pleased that the exhibition site arranged for by Greenough's brother was at the rival American Academy of Fine Arts. "You will I am sure, do me the justice to believe that had I been aware of it I should have countermanded the arrangement," Greenough wrote apologetically to Morse on January 5, 1832. "If those gen[tleme]n imagine that I am to be bamboozled into an approval of their association for the discouragement of art they will soon find their error" (quoted in Wright 1972, p. 102). Cherubs was seen again in New York, in the spring of 1832, when it marked Greenough's debut in an Academy annual exhibition.

Until he received the opportunity to sculpt the Chanting Cherubs group, Greenough had mainly produced portrait busts. But after demonstrating through that work his ability to create forms that were structurally and intellectually more complicated, other major commissions came to him. His first life-size marble, a recumbent Medora (1831-33, Baltimore Museum of Art), was executed for the distinguished Baltimore collector Robert Gilmor. Greenough's most significant commission came from the United States Congress, which in 1832 ordered a monumental image of George Washington (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.), intended for installation in the rotunda of the Capitol. This sculpture, on which he worked from 1832 until 1841, met with such a barrage of criticism-primarily for casting Washington in the role of Zeus, classically draped and bare-chested-that it was soon removed from the rotunda. Another major federal commission was The Rescue (1837-51), for the east front of the U.S. Capitol (U.S. Capitol, storage).

Greenough also made an indispensable contribution to American architectural theory with his well-known writings on form and function. The historian Nathalia Wright has called these "the first full and coherent public statement of the functional theory of architecture to be made by an American" (Wright 1963, p. 183).

Late in 1851 Greenough and his family gave up the expatriate life and returned to the Boston area. The next year he traveled frequently to Washington and New York in connection with his major projects, The Rescue and plans for an equestrian figure of George Washington for New York's Union Square, a work later completed by Henry Kirke Brown. Greenough suffered from a malady of the brain, and his condition, which had been deteriorating for a time, worsened during 1852. He died at the end of the year.

Because he lived abroad for so long, Greenough's association with the Academy was not as active as it might have been. He was an ardent supporter of the institution, as seen in his above-quoted letter to Morse, and a friend of a number of its leading members. He attended the Academy's antique classes during his stays in New York in 1827 and 1828 and held the appointment of the Academy's professor of sculpture from 1829 through 1836, although he was hardly available to perform instructional duties. His work was represented in Academy annuals from 1832 through 1835 and several times in the 1840s.

In appreciation of his election to honorary membership, Greenough wrote Morse in May 1828, offering a copy of the head of the Apollo Belvedere, which he had brought to America from Rome and which he "thought might be useful in your gallery" (Wright 1972, p. 11). Evidently Morse never availed himself of the offer, and the Apollo was probably that bust still in the possession of Mrs. Greenough in 1864, when it was shown at the Boston Athenaeum. A February 25, 1832, from a Leghorn, Italy, shipping agent to Academy secretary John L. Morton notes that Greenough directed the sending of "a Case of Pictures intended . . . for your National Academy . . . on board the Barque Prudent." No record of the contents of this case has surfaced, nor is its receipt noted in Academy minutes or evident in the collection. Greenough wrote Morton in March 1832 that he had "hopes of procuring several drawings by eminent artists for our academy." But again, it is not certain whether this beneficent attempt at acquisition was fulfilled (Wright 1972, p. 117).

Greenough's ambitions as a neoclassical sculptor and his attainments in the field, together with his support of the fledgling Academy, no doubt endeared him to its members. At Greenough's death, Asher B. Durand, in a eulogy written on behalf of the Council, expressed this esteem and took the opportunity to endorse the principle of cultural nationalism:

[block quote:]

Mr. Greenough may be justly regarded as the Father of American Sculpture. He has been taken from us in the prime of life, soon after his return from a foreign residence, to pursue his art at home.

Although his years have been spent abroad where he has earned a most distinguished fame, his great works adorn his own country and will descend to posterity among the noblest illustrations of her history. Greenough has done much towards the establishment of an American School of art and there are others, thank heaven, who still live alike entitled to our gratitude for their services in the noble cause. Who while they acknowledge the advantage of study in foreign schools to complete, so to speak, their art education, choose not to surrender their identity and pass away in the current of servile imitation. This is as it should be. Our National importance and power, our history and our scenery, exert a united influence which unimpeded by conventional schools, cannot fail to produce an original School of Art worthy to share the tribute of universal respect already paid to our condition of political advancement.

[end of block quote]