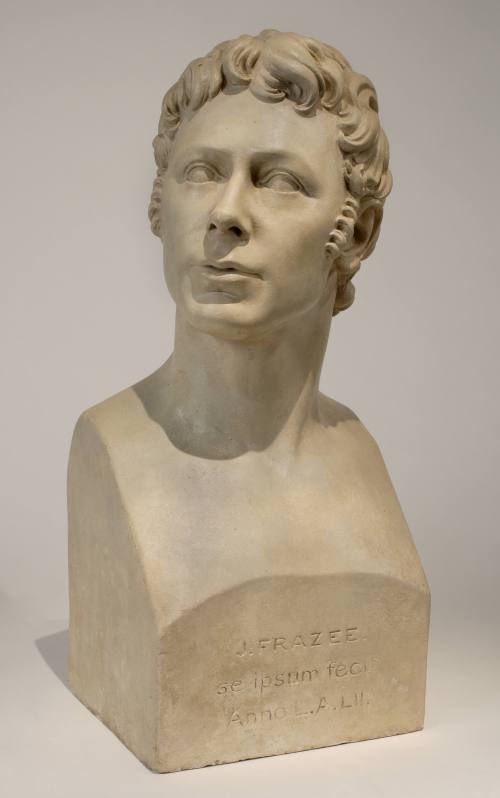

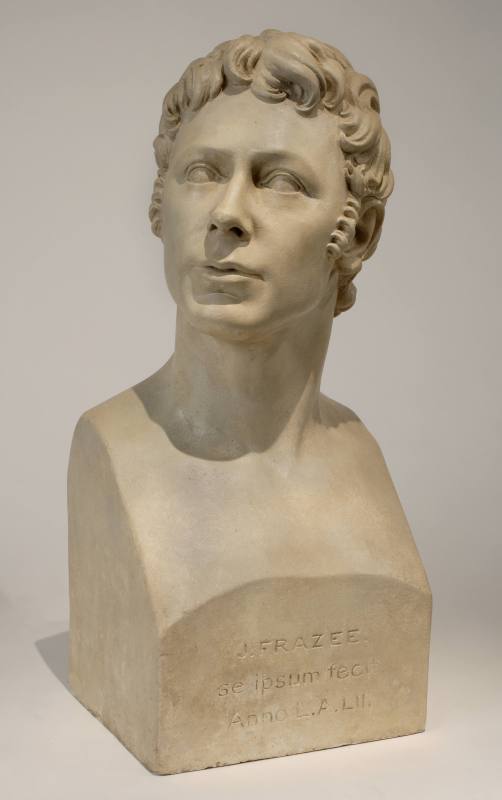

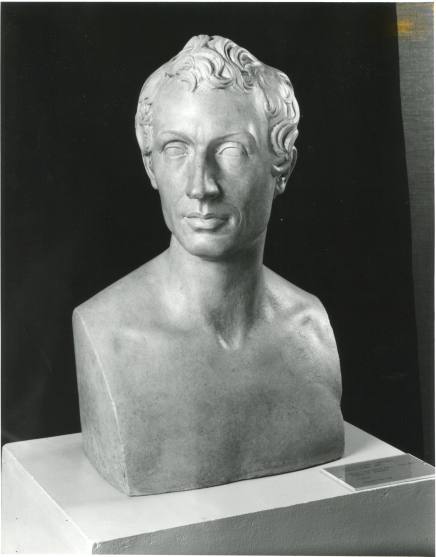

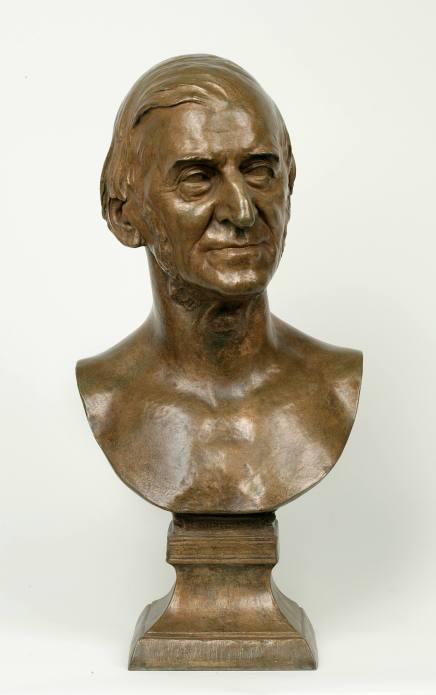

American, 1790 - 1852

For many historians, the history of American sculpture begins with John Frazee. His early life was spent on a New Jersey farm. At age fourteen he was indentured to William Lawrence, a local builder, under whom he worked for seven years. During this time Frazee developed an interest in drawing and calligraphy, talents Lawrence recognized and put to good use. He assigned Frazee to the execution of engraved tablets and ornamental stonework as well as general stonecutting.

Eventually Lawrence helped Frazee open his own marble yard, and by 1812, Frazee had a monopoly in the tombstone-cutting business in Rahway. This success prompted him to move in 1818 to New York, where, in partnership with his brother, he opened a shop for the carving of monuments, mantelpieces, and other decorative work. Frazee found many admirers of his work, and his business flourished. His talents for carving and calligraphy may be seen in his decorative memorials, such as that to Sarah Haynes (c. 1821, Trinity Church, New York). He also tried his hand at portraiture; his first bust, of his son Monroe, is now lost.

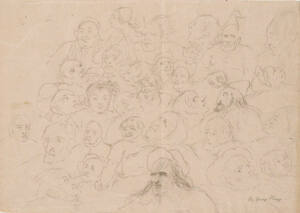

Through study of the plaster casts in the collection of the American Academy of Fine Arts, he was inspired to take a more artistic approach to his work. In 1824 he became a member of the American Academy, which accepted him as an artist rather than as an artisan. With the help of this organization, he gained permission to model a bust of the Marquis de Lafayette from life; this work garnered him further public attention and more portrait commissions. Yet Frazee was among the handful of New York artists, several of whom were also members of the American Academy (including William Dunlap, Charles Ingham, Henry Inman, and Samuel F. B. Morse), whose unsuccessful attempt to reform that organization resulted in the founding of the National Academy of Design. Frazee apparently felt little or no loyalty for the American Academy, and he even harbored some resentment for John Trumbull, its president. Dunlap recorded that Frazee considered Trumbull to be "cold and discouraging . . . and exclaims, 'Is such a man fit for a president of an Academy of Fine Art?'" The only sculptor to be a charter member of the Academy, Frazee served on the committee that organized its first exhibition in 1826; he showed two busts that year, including the one of Lafayette. He also was an early enrollee in the Academy school's antique class. However, unlike the activist founders of the National Academy, Frazee was never part of the inner circle that directed it. Also, after the first two annual exhibitions he showed only in the annuals of 1832, 1834, and 1841. The regulation that Thomas Cummings called "the unwise and unconstitutional law of 1834," which made failure to exhibit two years in a row grounds for demotion, resulted in Frazee's forfeiting his standing as an Academician.

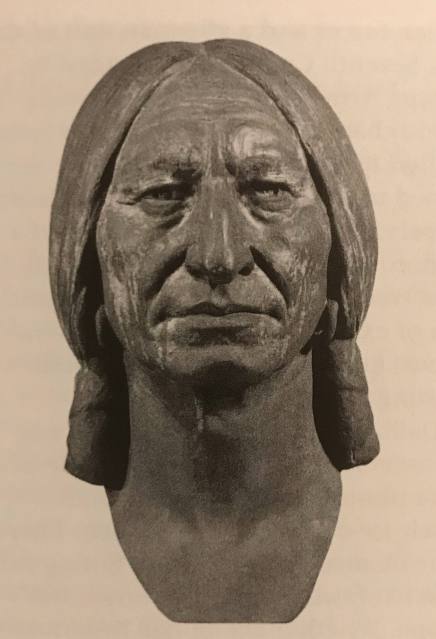

In his work, however, Frazee's reputation grew steadily throughout the late 1820s and 1830s. In 1831 he reorganized his business, forming a successful partnership with fellow sculptor Robert Launitz that lasted until 1837. Portrait commissions came to Frazee from many well-known subjects and institutions, including the Boston Athenaeum, which in 1833 commissioned a series of portraits of famous Americans. Publication of Frazee's autobiography in the North American Quarterly Magazine in 1835 gives some indication of his perceived importance in the art world of the period. Meanwhile, in 1834, the construction skills Frazee had gained in his apprenticeship helped him secure appointment as superintending architect for the uncompleted United States Customs House in New York. Using the original plans of Alexander Jackson Davis and Ithiel Town, Frazee reworked the design of the building, especially its interior. The project occupied him until 1841.

By the late 1830s ill health and personal loss (his beloved first wife, Jane, had died in 1832) had begun taking their toll. Most of his time was devoted to the Customs House project. He also became involved with designs for other monuments, mostly ill fated, and had less time for and interest in sculpting independent works. In 1843 Frazee was appointed customs inspector for New York, a position that provided him with a steady and respectable income. He spent the latter years of the decade designing a huge monument to George Washington for New York City that never came to fruition. His health deteriorated further in these years. He died while on a visit to his daughter in Rhode Island. Soon after, the Academy recorded this tribute:

[block quote:]

John Frazee . . . was a Sculptor and Architect, possessing talents and attainments which under more fortunate circumstances would have secured to him a high rank in the world of art. In the absence of such circumstances he has established a claim on our remembrance by his services during the infancy of the Academy, by the production of numerous meritorious busts of our distinguished men and by the erection of one of the most beautiful structures in our city.

[end of block quote]

Eventually Lawrence helped Frazee open his own marble yard, and by 1812, Frazee had a monopoly in the tombstone-cutting business in Rahway. This success prompted him to move in 1818 to New York, where, in partnership with his brother, he opened a shop for the carving of monuments, mantelpieces, and other decorative work. Frazee found many admirers of his work, and his business flourished. His talents for carving and calligraphy may be seen in his decorative memorials, such as that to Sarah Haynes (c. 1821, Trinity Church, New York). He also tried his hand at portraiture; his first bust, of his son Monroe, is now lost.

Through study of the plaster casts in the collection of the American Academy of Fine Arts, he was inspired to take a more artistic approach to his work. In 1824 he became a member of the American Academy, which accepted him as an artist rather than as an artisan. With the help of this organization, he gained permission to model a bust of the Marquis de Lafayette from life; this work garnered him further public attention and more portrait commissions. Yet Frazee was among the handful of New York artists, several of whom were also members of the American Academy (including William Dunlap, Charles Ingham, Henry Inman, and Samuel F. B. Morse), whose unsuccessful attempt to reform that organization resulted in the founding of the National Academy of Design. Frazee apparently felt little or no loyalty for the American Academy, and he even harbored some resentment for John Trumbull, its president. Dunlap recorded that Frazee considered Trumbull to be "cold and discouraging . . . and exclaims, 'Is such a man fit for a president of an Academy of Fine Art?'" The only sculptor to be a charter member of the Academy, Frazee served on the committee that organized its first exhibition in 1826; he showed two busts that year, including the one of Lafayette. He also was an early enrollee in the Academy school's antique class. However, unlike the activist founders of the National Academy, Frazee was never part of the inner circle that directed it. Also, after the first two annual exhibitions he showed only in the annuals of 1832, 1834, and 1841. The regulation that Thomas Cummings called "the unwise and unconstitutional law of 1834," which made failure to exhibit two years in a row grounds for demotion, resulted in Frazee's forfeiting his standing as an Academician.

In his work, however, Frazee's reputation grew steadily throughout the late 1820s and 1830s. In 1831 he reorganized his business, forming a successful partnership with fellow sculptor Robert Launitz that lasted until 1837. Portrait commissions came to Frazee from many well-known subjects and institutions, including the Boston Athenaeum, which in 1833 commissioned a series of portraits of famous Americans. Publication of Frazee's autobiography in the North American Quarterly Magazine in 1835 gives some indication of his perceived importance in the art world of the period. Meanwhile, in 1834, the construction skills Frazee had gained in his apprenticeship helped him secure appointment as superintending architect for the uncompleted United States Customs House in New York. Using the original plans of Alexander Jackson Davis and Ithiel Town, Frazee reworked the design of the building, especially its interior. The project occupied him until 1841.

By the late 1830s ill health and personal loss (his beloved first wife, Jane, had died in 1832) had begun taking their toll. Most of his time was devoted to the Customs House project. He also became involved with designs for other monuments, mostly ill fated, and had less time for and interest in sculpting independent works. In 1843 Frazee was appointed customs inspector for New York, a position that provided him with a steady and respectable income. He spent the latter years of the decade designing a huge monument to George Washington for New York City that never came to fruition. His health deteriorated further in these years. He died while on a visit to his daughter in Rhode Island. Soon after, the Academy recorded this tribute:

[block quote:]

John Frazee . . . was a Sculptor and Architect, possessing talents and attainments which under more fortunate circumstances would have secured to him a high rank in the world of art. In the absence of such circumstances he has established a claim on our remembrance by his services during the infancy of the Academy, by the production of numerous meritorious busts of our distinguished men and by the erection of one of the most beautiful structures in our city.

[end of block quote]