American, 1861 - 1944

Cyrus E. Dallin was descended from pioneer settlers of Utah, where he received his primary education. An early propensity for modeling in clay attracted the attention of two local mining investors, C. H. Blanchard and Jacob Lawrence, who financed Dallin's move to Boston in 1880. There he studied at Truman Bartlett's school and with the sculptor Sidney A. Morse, and he worked in a local terra-cotta factory. He also met his future wife and lifelong supporter, the author Vittoria Colonna Murray.

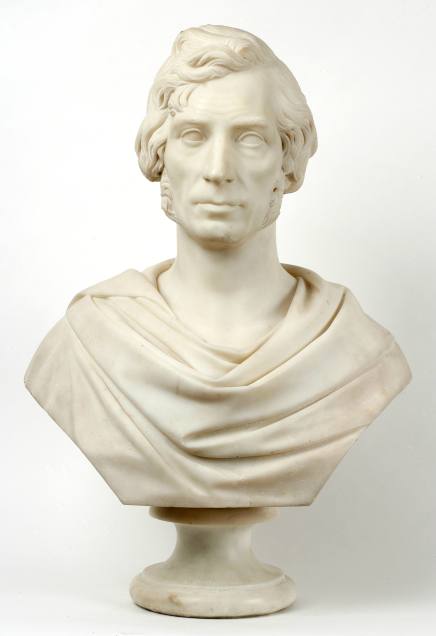

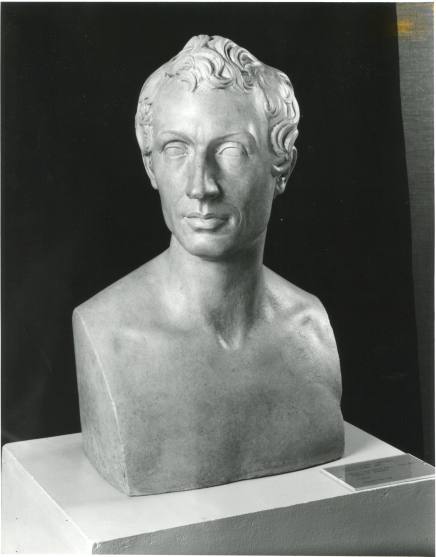

In 1882 Dallin established his own studio in Boston and began producing portrait busts and statuettes. Consequently, he was well placed to compete, in 1883, for the commission of an equestrian statue of Paul Revere financed by patriotic Bostonians. His model for the sculpture was completed and shown at the Boston Art Club early the following year. After some delay and several revisions, he was awarded the contract for the figure in 1885. Politics and procrastination postponed the unveiling of the finished bronze to 1940, causing the work to be a lifelong burden but a happy fulfillment of Dallin's old age.

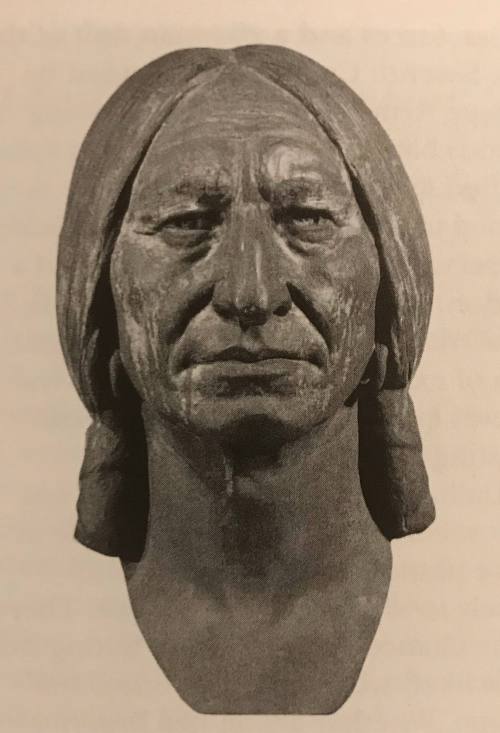

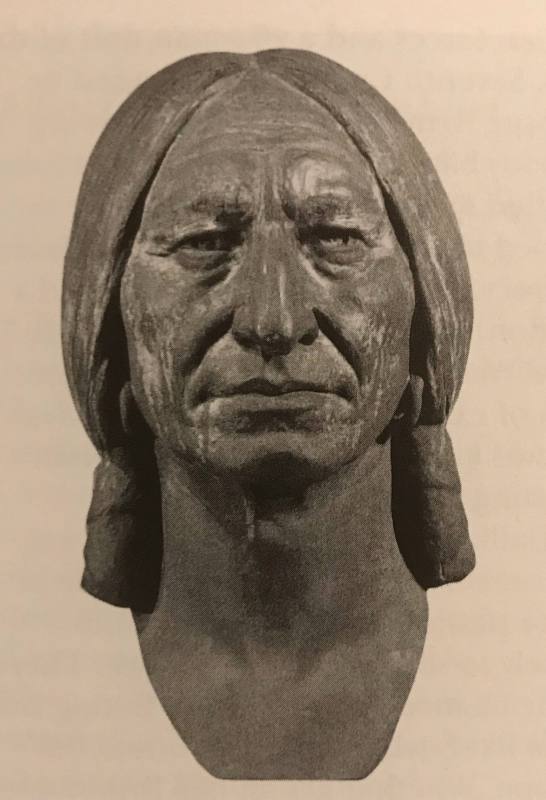

In the mid-1880s, Dallin began experimenting with figures of the American Indian, a genre with which he was to be identified for the rest of his life. In 1888 he sent one of these, The Indian Hunter, to the American Art Association exhibition in New York, where it was awarded a Gold Medal. The following year, he went to Paris, entered the Académie Julian, and studied with Henri Michel Chapu. He passed the concours for the Ecole des Beaux-Arts but chose not to matriculate. Instead, he busied himself with a commission given by an American for an equestrian statue of the Marquis de Lafayette, conceived as a gift to France from the American people. The model, cast in bronze, was shown at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889.

Dallin continued his interest in Native American, and therefore non-academic, subject matter. At the Salon in 1890 he exhibited The Signal of Peace (Lincoln Park, Chicago), an equestrian Indian composition inspired by the European tour of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. The work was shown in Chicago in 1893 at the World's Columbian Exposition and made Dallin's fame. As the author and critic William Howe Downes pointed out in 1899, it "marked the ripening of the sculptor's talent and the opening of a distinct period of original productiveness." The 1890s brought several major commissions to Dallin, including a full-length Isaac Newton for the Library of Congress and the gilded angel atop the Mormon Temple in Salt Lake City. He spent part of the 1890s in the latter city and then taught for a time at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia.

Yet Dallin was not satisfied with his artistic training, and in 1896 he returned to Paris and entered the atelier of the sculptor Jean Dampt. He produced several important groups and equestrian sculptures during these years and exhibited in the Salons of 1897, 1898, and 1899. In 1900 his Medicine Man (Fairmount Park, Philadelphia) received a silver medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris; the following year it was placed in front of the Art Building at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

Dallin returned to America in 1899 and settled permanently in Arlington Heights, near Boston. He took a position at the Massachusetts State Normal Art School in Boston, where he taught until 1942. The last of his large equestrian Indian figures, The Appeal of the Great Spirit, conceived in the first decade of the century, was bought by the City of Boston in 1912 and installed in front of the Museum of Fine Arts, making it today his most familiar work. It is a permanent reminder of the characteristic placement of Dallin's larger works during his lifetime: at the entrances to buildings housing art exhibitions.

During the last three decades of his life, Dallin was fortunate enough to have Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge as a major patron. In 1931, she commissioned The Passing of the Buffalo (now in Muncie, Indiana) from him for Giralda, her estate in Madison, New Jersey. Eventually she owned twenty-one of his bronzes, the largest collection of his work at the time.

From 1902 Dallin was a regular participant in Academy exhibitions. Almost every work shown had an American Indian theme. In 1911 The Appeal to the Great Spirit was installed in the entrance hall of the Academy's galleries at 215 West Fifty-seventh Street.

Dallin was also a member of the National Sculpture Society, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the Architectural League of New York, the Boston Society of Sculptors, the Saint Botolph Club, the Boston Art Club, the Indian Association, the Japan Society, and the Royal Society of Arts, London.

In 1882 Dallin established his own studio in Boston and began producing portrait busts and statuettes. Consequently, he was well placed to compete, in 1883, for the commission of an equestrian statue of Paul Revere financed by patriotic Bostonians. His model for the sculpture was completed and shown at the Boston Art Club early the following year. After some delay and several revisions, he was awarded the contract for the figure in 1885. Politics and procrastination postponed the unveiling of the finished bronze to 1940, causing the work to be a lifelong burden but a happy fulfillment of Dallin's old age.

In the mid-1880s, Dallin began experimenting with figures of the American Indian, a genre with which he was to be identified for the rest of his life. In 1888 he sent one of these, The Indian Hunter, to the American Art Association exhibition in New York, where it was awarded a Gold Medal. The following year, he went to Paris, entered the Académie Julian, and studied with Henri Michel Chapu. He passed the concours for the Ecole des Beaux-Arts but chose not to matriculate. Instead, he busied himself with a commission given by an American for an equestrian statue of the Marquis de Lafayette, conceived as a gift to France from the American people. The model, cast in bronze, was shown at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889.

Dallin continued his interest in Native American, and therefore non-academic, subject matter. At the Salon in 1890 he exhibited The Signal of Peace (Lincoln Park, Chicago), an equestrian Indian composition inspired by the European tour of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. The work was shown in Chicago in 1893 at the World's Columbian Exposition and made Dallin's fame. As the author and critic William Howe Downes pointed out in 1899, it "marked the ripening of the sculptor's talent and the opening of a distinct period of original productiveness." The 1890s brought several major commissions to Dallin, including a full-length Isaac Newton for the Library of Congress and the gilded angel atop the Mormon Temple in Salt Lake City. He spent part of the 1890s in the latter city and then taught for a time at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia.

Yet Dallin was not satisfied with his artistic training, and in 1896 he returned to Paris and entered the atelier of the sculptor Jean Dampt. He produced several important groups and equestrian sculptures during these years and exhibited in the Salons of 1897, 1898, and 1899. In 1900 his Medicine Man (Fairmount Park, Philadelphia) received a silver medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris; the following year it was placed in front of the Art Building at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

Dallin returned to America in 1899 and settled permanently in Arlington Heights, near Boston. He took a position at the Massachusetts State Normal Art School in Boston, where he taught until 1942. The last of his large equestrian Indian figures, The Appeal of the Great Spirit, conceived in the first decade of the century, was bought by the City of Boston in 1912 and installed in front of the Museum of Fine Arts, making it today his most familiar work. It is a permanent reminder of the characteristic placement of Dallin's larger works during his lifetime: at the entrances to buildings housing art exhibitions.

During the last three decades of his life, Dallin was fortunate enough to have Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge as a major patron. In 1931, she commissioned The Passing of the Buffalo (now in Muncie, Indiana) from him for Giralda, her estate in Madison, New Jersey. Eventually she owned twenty-one of his bronzes, the largest collection of his work at the time.

From 1902 Dallin was a regular participant in Academy exhibitions. Almost every work shown had an American Indian theme. In 1911 The Appeal to the Great Spirit was installed in the entrance hall of the Academy's galleries at 215 West Fifty-seventh Street.

Dallin was also a member of the National Sculpture Society, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the Architectural League of New York, the Boston Society of Sculptors, the Saint Botolph Club, the Boston Art Club, the Indian Association, the Japan Society, and the Royal Society of Arts, London.