1863 - 1937

MacMonnies showed an interest in art, specifically in drawing and modeling, when he was young; but his father's financial problems, which had originated during the the Civil War, made it mandatory that Frederick work during his teens at various jobs unrelated to art. A break came in 1880, however, when he was hired as a studio assistant by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Thereafter, his progress in the field of sculpting was steady.

Saint-Gaudens, with whom MacMonnies remained friends for life, urged the younger artist to enroll in the life classes at the National Academy, which he did beginning in 1881, and at the Art Students League. In 1884, MacMonnies won the Silver Suydam Medal for his work in the Academy's Life Class.

That same year, at the age of twenty, MacMonnies went to Paris to continue his education at the Acad‚mie Colarossi. An outbreak of cholera prompted him to leave Paris, temporarily, and go to Munich where he enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts near the end of 1884. He went back to America in the late winter of 1885 to work with Saint-Gaudens but returned to Paris the following year. During this, his second stay in the city, he matriculated at the Ecole des-Beaux-Arts where he studied with and served as studio assistant to the sculptor Alexandre Falgui‚re. MacMonnies' own work soon began receiving some critical attention and, on Falgui‚re's advice, he opened his own studio in Paris. As early as 1883, he began sending portrait busts and reliefs to America for exhibition at the Society of American Artists in New York, and in 1889, his works began appearing at the Paris Salons. Commercial success came to MacMonnies through the creation of several small bronzes, beginning in 1890. These were meant for private consumption and domestic display and included the Pan of Rohallion (1890), executed on a commission from Edward Dean Adams, a New Jersey banker; Young Faun and Heron (1890), commissioned for the home of Joseph Hodges Choate in Stockbridge, Massachusetts; and Diana (see below).

MacMonnies' reputation grew when his statue of Nathan Hale, which was the winner of a competition for a portrait of Hale to be erected in City Hall Park in New York, won a medal at the Salon of 1891; and the sculptor's fame was assured when he received the commission for a huge fountain for the World's Columbian Exposition which was held in Chicago in 1893. The latter work, executed in plaster, was an elaborate sculptural group known as the "MacMonnies' Fountain", "The Columbian Fountain," or "The Barge of State", and was one of the major attractions of the Fair.

The volume of commissions which MacMonnies recieved during the final decade of the 19th century was impressive. Among these were two fountains for the New York Public Library, a full-length portrait statue of Shakespeare for the Library of Congress, an equestrian of General Slocum for the city of Brooklyn, and a quadriga for the Prospect Park Memorial Arch, also in Brooklyn. MacMonnies' Bacchante and Infant Faun (1892-93), executed for the courtyard of the Boston Public Library, was a succ‚s de scandale. Interpreted as too decadent, the sculpture was eventually rejected by the Library and was subsequently given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. During this same decade, MacMonnies taught at the Vitti School and, briefly, at the Acad‚mie Carmen in Paris. His reputation was affirmed in 1896 when he was given the title Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the nation of France and again, in 1898, when he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in New York.

On a personal level, however, not all was well with MacMonnies. Following a nervous breakdown around 1900, he turned to painting for a time. But negative critical reactions to his work in that genre caused him to return to sculpting in 1905, and again he produced a number of major pieces. In that year, too, he established a studio-school at Giverny not far from the home of Monet. Among the projects of his final years was Civic Virtue, an allegorical, nude, overly robust, Hercules-like figure done for the city of New York. It caused a stir in the press and set off a controversy matched only by that which had been prompted earlier by MacMonnies' Bacchante. In the midst of the crisis, the Council of the National Academy called a special meeting on March 26, 1922, to voice their support of the sculptor by passing a resolution defending him and his work.

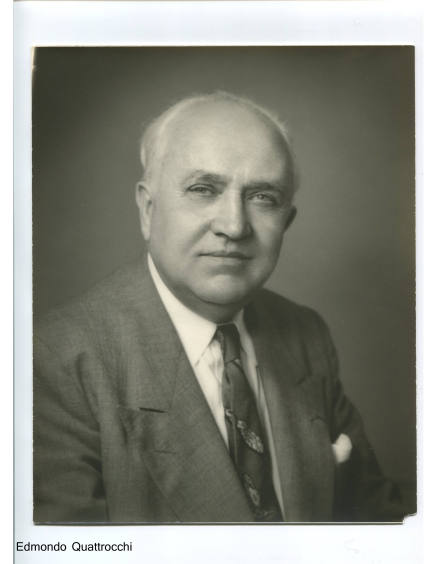

One of MacMonnies' last major commissions was a monument commemorating the Battle of the Marne, featuring a huge figure called France Defiant. It was executed for the city of Meaux, France, in collaboration with the American sculptor Edmondo Quattrocchi.

MacMonnies was married twice; his first wife was the painter Mary Louise Fairchild, whom he married in 1888. Following their divorce, he married, secondly, to Alice Jones in 1910. (Mary Fairchild MacMonnies had remarried, in 1909, to the artist Will Low). They lived in France until the outbreak of World War I in 1914 when they moved to New York where the sculptor lived for the rest of his life. He maintained ties to France, however, traveling there a number of times over the decades prior to his death.

Saint-Gaudens, with whom MacMonnies remained friends for life, urged the younger artist to enroll in the life classes at the National Academy, which he did beginning in 1881, and at the Art Students League. In 1884, MacMonnies won the Silver Suydam Medal for his work in the Academy's Life Class.

That same year, at the age of twenty, MacMonnies went to Paris to continue his education at the Acad‚mie Colarossi. An outbreak of cholera prompted him to leave Paris, temporarily, and go to Munich where he enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts near the end of 1884. He went back to America in the late winter of 1885 to work with Saint-Gaudens but returned to Paris the following year. During this, his second stay in the city, he matriculated at the Ecole des-Beaux-Arts where he studied with and served as studio assistant to the sculptor Alexandre Falgui‚re. MacMonnies' own work soon began receiving some critical attention and, on Falgui‚re's advice, he opened his own studio in Paris. As early as 1883, he began sending portrait busts and reliefs to America for exhibition at the Society of American Artists in New York, and in 1889, his works began appearing at the Paris Salons. Commercial success came to MacMonnies through the creation of several small bronzes, beginning in 1890. These were meant for private consumption and domestic display and included the Pan of Rohallion (1890), executed on a commission from Edward Dean Adams, a New Jersey banker; Young Faun and Heron (1890), commissioned for the home of Joseph Hodges Choate in Stockbridge, Massachusetts; and Diana (see below).

MacMonnies' reputation grew when his statue of Nathan Hale, which was the winner of a competition for a portrait of Hale to be erected in City Hall Park in New York, won a medal at the Salon of 1891; and the sculptor's fame was assured when he received the commission for a huge fountain for the World's Columbian Exposition which was held in Chicago in 1893. The latter work, executed in plaster, was an elaborate sculptural group known as the "MacMonnies' Fountain", "The Columbian Fountain," or "The Barge of State", and was one of the major attractions of the Fair.

The volume of commissions which MacMonnies recieved during the final decade of the 19th century was impressive. Among these were two fountains for the New York Public Library, a full-length portrait statue of Shakespeare for the Library of Congress, an equestrian of General Slocum for the city of Brooklyn, and a quadriga for the Prospect Park Memorial Arch, also in Brooklyn. MacMonnies' Bacchante and Infant Faun (1892-93), executed for the courtyard of the Boston Public Library, was a succ‚s de scandale. Interpreted as too decadent, the sculpture was eventually rejected by the Library and was subsequently given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. During this same decade, MacMonnies taught at the Vitti School and, briefly, at the Acad‚mie Carmen in Paris. His reputation was affirmed in 1896 when he was given the title Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the nation of France and again, in 1898, when he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in New York.

On a personal level, however, not all was well with MacMonnies. Following a nervous breakdown around 1900, he turned to painting for a time. But negative critical reactions to his work in that genre caused him to return to sculpting in 1905, and again he produced a number of major pieces. In that year, too, he established a studio-school at Giverny not far from the home of Monet. Among the projects of his final years was Civic Virtue, an allegorical, nude, overly robust, Hercules-like figure done for the city of New York. It caused a stir in the press and set off a controversy matched only by that which had been prompted earlier by MacMonnies' Bacchante. In the midst of the crisis, the Council of the National Academy called a special meeting on March 26, 1922, to voice their support of the sculptor by passing a resolution defending him and his work.

One of MacMonnies' last major commissions was a monument commemorating the Battle of the Marne, featuring a huge figure called France Defiant. It was executed for the city of Meaux, France, in collaboration with the American sculptor Edmondo Quattrocchi.

MacMonnies was married twice; his first wife was the painter Mary Louise Fairchild, whom he married in 1888. Following their divorce, he married, secondly, to Alice Jones in 1910. (Mary Fairchild MacMonnies had remarried, in 1909, to the artist Will Low). They lived in France until the outbreak of World War I in 1914 when they moved to New York where the sculptor lived for the rest of his life. He maintained ties to France, however, traveling there a number of times over the decades prior to his death.