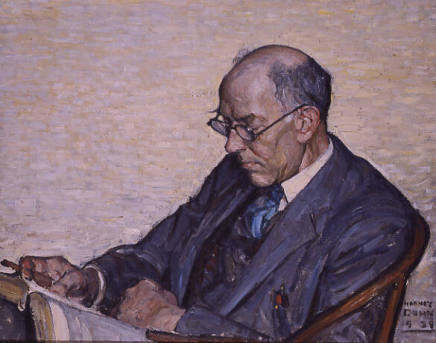

American, 1808 - 1889

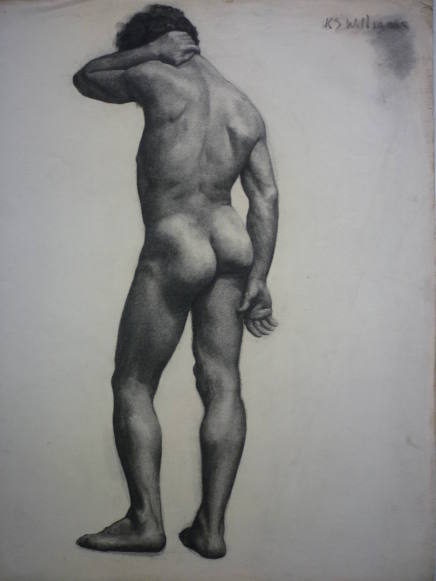

John Gadsby Chapman's artistic aspirations were first encouraged by the portraitist Charles Bird King, who from 1819 was the senior artist living in nearby Washington, D.C. King lent him casts from which to practice drawing skills and develop perception of classical form. Chapman left Alexandria in 1827 and, after briefly residing in Winchester, Virginia, moved to Philadelphia. There he met Thomas Sully, who encouraged him and arranged for him to study under the drawing master Pietro Ancora. Chapman soon became discouraged with these studies and, with funds borrowed from family and friends, embarked in 1828 for Italy. For the next three years he studied the works of the Old Masters in Florence, Rome, and Naples, and became acquainted with other American artists working abroad, including Horatio Greenough and Samuel F. B. Morse. Following his return to America in 1831, Chapman divided his time between New York and Alexandria, which provided easy access to sites of some of his favorite subjects as well as patronage. His copies of paintings by the Old Masters, made during his years in Italy, were well received in both cities, and he soon began receiving commissions for original compositions.

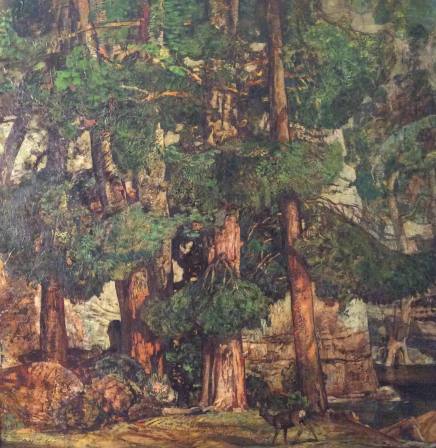

Although Chapman worked in landscape and portraiture, his ambition, which he pursued aggressively, was history painting. He first exhibited in an Academy annual in 1833, represented by just one work, a scene from Cervantes's Don Quixote. However, in succeeding years until his return to Europe, he was an especially prolific exhibitor, showing portraits, genre, literary, and religious subjects and European and American landscape scenes-many of which bore associations to historical events or celebrities. In the 1830s he concentrated on a series of historical landscapes of Mount Vernon and other places associated with the life and career of George Washington. These paintings, especially, met with instant success and were subsequently engraved by John F. E. Prud'homme.

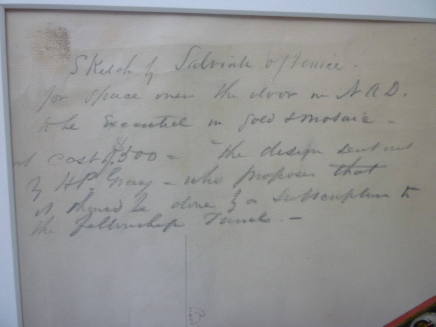

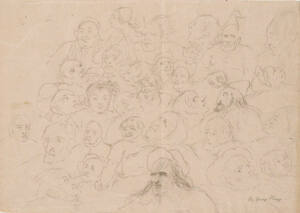

In the second quarter of the nineteenth century the major hope and opportunity of American painters who aspired to the highest expressive form of their art-historical themes rendered on a grand scale-were the four panels in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, which, out of a total of eight, remained blank. John Trumbull, who had expected to be awarded all eight, was instead allowed only four; these were completed by 1824. More than a decade passed before the fate of the remaining spaces was decided. Because Congress was to issue the commissions, competition was keen and was bound up with political considerations. In 1837 they were awarded to Henry Inman (who did not live to carry his out), John Vanderlyn, Robert F. Weir, and Chapman, the only one of the group not primarily associated with New York. Chapman had lobbied for the commission, and it was largely due to the efforts of his old friend the Virginia Congressman Henry Wise that he was successful. His contribution to the suite was a topically Virginian, as well as universally Christian subject, The Baptism of Pocahontas. The painting was completed in 1840.

By 1843 Chapman had begun preparing his American Drawing-Book, a treatise to assist professional artists in their studies. The book was published in 1847 to instant acclaim and enjoyed many subsequent editions. But it was in the illustrating of books, rather than the writing of them, that Chapman made his special mark. Parallel to his work as a painter was a thriving career as an engraver. Although his contributions to all forms of illustrated publication of the 1830s and 1840s was prodigious, none approached the scale, or yielded the fame, of his fourteen hundred designs made between 1843 and 1846, executed in wood engravings for Harper's Illuminated Bible.

Chapman was elected to the Academy's Council in 1843. The following spring he became recording secretary and, a year later, corresponding secretary of the Academy, a post to which he was twice reelected. Thus he participated continuously in Academy governance from 1843 through the spring of 1848. Later that year he returned to Europe. After living briefly in London and Paris in the autumn of 1850 he settled in Rome, where he remained for thirty-four years. He frequently was plagued by financial problems. To turn to advantage the market created by Americans taking the Grand Tour, Chapman increasingly painted picturesque Italian genre and landscape scenes, which made excellent souvenirs. Eventually the taste for these paintings waned, and in 1884, with this mainstay of his income failing, he returned to America. After a brief visit to New York, he traveled to Mexico to join his son, the painter Conrad Wise Chapman, but was back in New York for what proved to be the final months of his life.

Although Chapman worked in landscape and portraiture, his ambition, which he pursued aggressively, was history painting. He first exhibited in an Academy annual in 1833, represented by just one work, a scene from Cervantes's Don Quixote. However, in succeeding years until his return to Europe, he was an especially prolific exhibitor, showing portraits, genre, literary, and religious subjects and European and American landscape scenes-many of which bore associations to historical events or celebrities. In the 1830s he concentrated on a series of historical landscapes of Mount Vernon and other places associated with the life and career of George Washington. These paintings, especially, met with instant success and were subsequently engraved by John F. E. Prud'homme.

In the second quarter of the nineteenth century the major hope and opportunity of American painters who aspired to the highest expressive form of their art-historical themes rendered on a grand scale-were the four panels in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, which, out of a total of eight, remained blank. John Trumbull, who had expected to be awarded all eight, was instead allowed only four; these were completed by 1824. More than a decade passed before the fate of the remaining spaces was decided. Because Congress was to issue the commissions, competition was keen and was bound up with political considerations. In 1837 they were awarded to Henry Inman (who did not live to carry his out), John Vanderlyn, Robert F. Weir, and Chapman, the only one of the group not primarily associated with New York. Chapman had lobbied for the commission, and it was largely due to the efforts of his old friend the Virginia Congressman Henry Wise that he was successful. His contribution to the suite was a topically Virginian, as well as universally Christian subject, The Baptism of Pocahontas. The painting was completed in 1840.

By 1843 Chapman had begun preparing his American Drawing-Book, a treatise to assist professional artists in their studies. The book was published in 1847 to instant acclaim and enjoyed many subsequent editions. But it was in the illustrating of books, rather than the writing of them, that Chapman made his special mark. Parallel to his work as a painter was a thriving career as an engraver. Although his contributions to all forms of illustrated publication of the 1830s and 1840s was prodigious, none approached the scale, or yielded the fame, of his fourteen hundred designs made between 1843 and 1846, executed in wood engravings for Harper's Illuminated Bible.

Chapman was elected to the Academy's Council in 1843. The following spring he became recording secretary and, a year later, corresponding secretary of the Academy, a post to which he was twice reelected. Thus he participated continuously in Academy governance from 1843 through the spring of 1848. Later that year he returned to Europe. After living briefly in London and Paris in the autumn of 1850 he settled in Rome, where he remained for thirty-four years. He frequently was plagued by financial problems. To turn to advantage the market created by Americans taking the Grand Tour, Chapman increasingly painted picturesque Italian genre and landscape scenes, which made excellent souvenirs. Eventually the taste for these paintings waned, and in 1884, with this mainstay of his income failing, he returned to America. After a brief visit to New York, he traveled to Mexico to join his son, the painter Conrad Wise Chapman, but was back in New York for what proved to be the final months of his life.