1874 - 1954

Evelyn Longman had her early education in Chicago, financed by her own savings earned from employment in a local business. She studied painting for a short time but soon decided on a career as a sculptor and, in 1898, enrolled in the modeling classes of Lorado Taft at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In 1900 she went to New York and worked with Hermon MacNeil and then Isidore Konti on decorative sculptures for the Pan-American Exposition to be held in Buffalo. More artistic education came in the New York studio of Daniel Chester French where she remained for three years. Her debut as an artist in her own right came with her work for the St. Louis Exposition in 1904. This was followed in 1906 by commissions for two sets of doors, the first for the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, and the second for the Wellesley College Library. Longman had gained some experience in this genre when she assisted French in the completion of his bronze doors for the Boston Public Library.

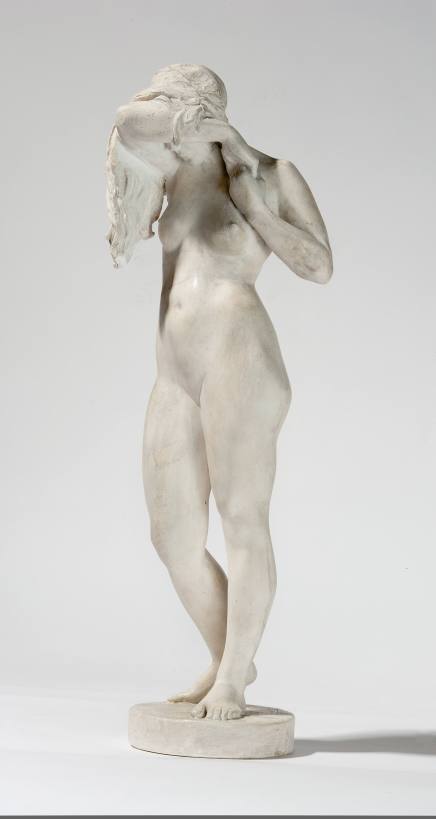

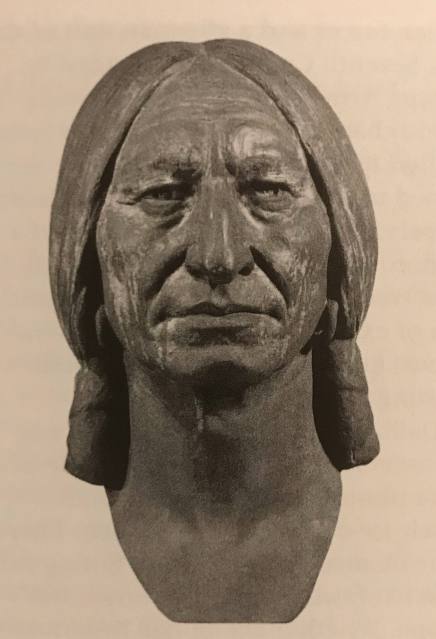

She was also soon executing portrait reliefs, including one of her former teacher, French, and busts, mostly in marble, such as that of French's daughter, Margaret, shown as Peggy at the Academy in the winter of 1912. Longman had begun exhibiting here in 1907 and most of the early works she showed here were portraits. Starting with the winter exhibition of 1912, however, she began to show a wider variety of allegorical works which, as Beatrice Proske has written, "embody her private vision of universal themes." The titles of these give some hint as to their expressive and/or dramatic nature: The Future, Victory, Study for Head of Republic, Consecration. Allegory became a speciality of the sculptor. Most of these pieces were designed in connection with a specific architecural setting. For example, the most famous, Electricity (a.k.a. The Spirit of Communication or The Genius of Telegraphy), once surmounted the American Telephone and Telegraph building in New York and is now housed that company's most recent headquarters. The success of this monument led to Longman's six-feet-high version of her earlier bust of Edison which had been taken from life. The huge replica was unveiled at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington in 1952.

Although she was not the first female sculptor to be elected to the Academy as has often been stated, Longman nonetheless made her impression upon the organization. She won the Julia A. Shaw Memorial Prize twice, in 1918 for The Future and in 1926 for a larger-than-life-size bust of Ivan Olinsky; and the Elizabeth N. Watrous Gold Medal in 1923 for A Memorial to Theodore C. Williams.

Following her marriage in 1920 to Nathaniel H. Batchelder, headmaster of the Loomis and Chaffee Schools in Windsor, Connecticut, the sculptor built a studio near the school. She and her family summered on Cape Cod where she kept another, smaller studio. She maintained her professional output, coupled with her duties as a headmaster's wife, in these two locations for the rest of her life.

In 1900 she went to New York and worked with Hermon MacNeil and then Isidore Konti on decorative sculptures for the Pan-American Exposition to be held in Buffalo. More artistic education came in the New York studio of Daniel Chester French where she remained for three years. Her debut as an artist in her own right came with her work for the St. Louis Exposition in 1904. This was followed in 1906 by commissions for two sets of doors, the first for the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, and the second for the Wellesley College Library. Longman had gained some experience in this genre when she assisted French in the completion of his bronze doors for the Boston Public Library.

She was also soon executing portrait reliefs, including one of her former teacher, French, and busts, mostly in marble, such as that of French's daughter, Margaret, shown as Peggy at the Academy in the winter of 1912. Longman had begun exhibiting here in 1907 and most of the early works she showed here were portraits. Starting with the winter exhibition of 1912, however, she began to show a wider variety of allegorical works which, as Beatrice Proske has written, "embody her private vision of universal themes." The titles of these give some hint as to their expressive and/or dramatic nature: The Future, Victory, Study for Head of Republic, Consecration. Allegory became a speciality of the sculptor. Most of these pieces were designed in connection with a specific architecural setting. For example, the most famous, Electricity (a.k.a. The Spirit of Communication or The Genius of Telegraphy), once surmounted the American Telephone and Telegraph building in New York and is now housed that company's most recent headquarters. The success of this monument led to Longman's six-feet-high version of her earlier bust of Edison which had been taken from life. The huge replica was unveiled at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington in 1952.

Although she was not the first female sculptor to be elected to the Academy as has often been stated, Longman nonetheless made her impression upon the organization. She won the Julia A. Shaw Memorial Prize twice, in 1918 for The Future and in 1926 for a larger-than-life-size bust of Ivan Olinsky; and the Elizabeth N. Watrous Gold Medal in 1923 for A Memorial to Theodore C. Williams.

Following her marriage in 1920 to Nathaniel H. Batchelder, headmaster of the Loomis and Chaffee Schools in Windsor, Connecticut, the sculptor built a studio near the school. She and her family summered on Cape Cod where she kept another, smaller studio. She maintained her professional output, coupled with her duties as a headmaster's wife, in these two locations for the rest of her life.