1885 - 1966

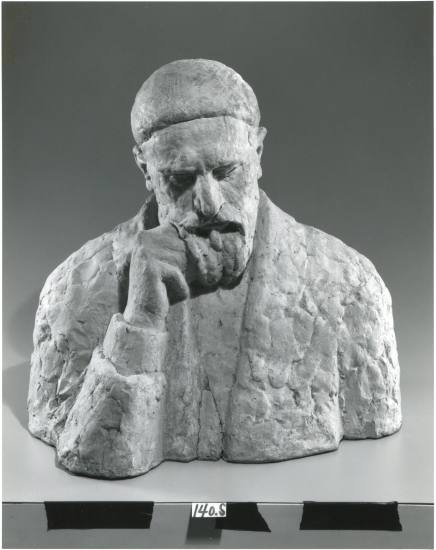

Malvina Hoffman grew up in the intellectually heady atmosphere surrounding her talented and successful father, the noted piano virtuoso Richard Hoffman, who counted among his acquaintances Jenny Lind and Franz Liszt. She began her art studies at the Woman's School of Applied Design, the Art Students League, and the Veltin School in New York, working there under Herbert Adams and George Grey Barnard. In 1906 she began taking painting classes with John White Alexander, who also encouraged her to explore sculpture. Her first finished piece, a bust of her father, was exhibited in plaster at the National Academy in 1909; its reception there encouraged her to pursue a career in sculpture.

In 1910, accompanied by her newly widowed mother, Hoffman went to Europe. She spent a few months in Italy before going to Paris, where she sought out Auguste Rodin, whose works she had seen in a private collection in New York. She worked under the French master intermittently until 1914 but remained aesthetically independent, pursuing subject matter that most interested her and not allowing either Rodin's style or thematic tastes to overwhelm her. While in Paris she also was an assistant to the American sculptor Janet Scudder.

Nowhere is Hoffman's early style more apparent than in her figures taken from the ballet. She soon counted among her friends the great dancers Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky, and her images of these and other dance-world personages made Hoffman famous. One such work, Russian Dancers (1911, Detroit Institute of Arts; Madison Art Center, Madison, Wisconsin), was exhibited at the National Academy in 1911 and in the Paris Salon in the spring of 1912. Hoffman was still executing images of Pavlova as late as 1923, when she did a plaster bust of the Russian star (New-York Historical Society). Related to these are a group of Bacchanale-inspired sculptures, friezes, and other works that capture the flow of the dancers' classical dress and their movements. Hoffman's Bacchanale Russe (1912), a version of which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, won the Julia A. Shaw Memorial Prize at the Academy in 1917; the following year a heroic-size casting of it was placed in the Luxembourg Gardens, Paris.

After World War I Hoffman settled in New York and was soon at work on a memorial, Sacrifice, a version of which was eventually placed in Harvard University's War Memorial Chapel. She helped reinstall Rodin's works in the Museé Luxembourg, worked on the initial cataloguing of works for the Musée Rodin, Paris, in 1919, and designed pedimental sculpture for Bush House, London.

The first major exhibition of Hoffman's work was held in 1929 at the Grand Central Galleries, New York. Later that year she received her most publicized commission when Stanley Field, director of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, invited her to undertake the immense project of recording in sculpture the various races of humanity. To that end, she spent eight months in 1931-32 on a much publicized round-the-world tour producing anthropologically correct and representative busts and figures. The sculptor related these travels in her 1936 book Heads and Tales. The artistic results of her efforts were unveiled in the Field Museum's Hall of Man in 1933.

More traditional portrait busts, which she executed throughout her career, include those of the pianist Ignace Paderewski, the sculptor Ivan Mestrovic, and the industrialist Henry Clay Frick. Examples of a number of these are in the collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Hoffman was an active participant in the New York art world. Her Sniffen Court studio became a salon of sorts for her many friends, among whom were Mestrovic, Paderewski, and the poet Marianne Moore. She exhibited at the Academy throughout her career; among her many awards were the Helen Foster Barnett Prize, which she won in 1921, and the Elizabeth N. Watrous Gold Medal, which she received in the winter of 1924 for a portrait of Pavlova. She was a member of the National Sculpture Society, New York. Among her three books was the historical and technical guide Sculpture Inside and Out (1939).

Hoffman made a generous monetary bequest to the Academy for the establishment of an annual prize in sculpture. She also left the Academy an assortment of casts and sculpting tools and materials.

In 1910, accompanied by her newly widowed mother, Hoffman went to Europe. She spent a few months in Italy before going to Paris, where she sought out Auguste Rodin, whose works she had seen in a private collection in New York. She worked under the French master intermittently until 1914 but remained aesthetically independent, pursuing subject matter that most interested her and not allowing either Rodin's style or thematic tastes to overwhelm her. While in Paris she also was an assistant to the American sculptor Janet Scudder.

Nowhere is Hoffman's early style more apparent than in her figures taken from the ballet. She soon counted among her friends the great dancers Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky, and her images of these and other dance-world personages made Hoffman famous. One such work, Russian Dancers (1911, Detroit Institute of Arts; Madison Art Center, Madison, Wisconsin), was exhibited at the National Academy in 1911 and in the Paris Salon in the spring of 1912. Hoffman was still executing images of Pavlova as late as 1923, when she did a plaster bust of the Russian star (New-York Historical Society). Related to these are a group of Bacchanale-inspired sculptures, friezes, and other works that capture the flow of the dancers' classical dress and their movements. Hoffman's Bacchanale Russe (1912), a version of which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, won the Julia A. Shaw Memorial Prize at the Academy in 1917; the following year a heroic-size casting of it was placed in the Luxembourg Gardens, Paris.

After World War I Hoffman settled in New York and was soon at work on a memorial, Sacrifice, a version of which was eventually placed in Harvard University's War Memorial Chapel. She helped reinstall Rodin's works in the Museé Luxembourg, worked on the initial cataloguing of works for the Musée Rodin, Paris, in 1919, and designed pedimental sculpture for Bush House, London.

The first major exhibition of Hoffman's work was held in 1929 at the Grand Central Galleries, New York. Later that year she received her most publicized commission when Stanley Field, director of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, invited her to undertake the immense project of recording in sculpture the various races of humanity. To that end, she spent eight months in 1931-32 on a much publicized round-the-world tour producing anthropologically correct and representative busts and figures. The sculptor related these travels in her 1936 book Heads and Tales. The artistic results of her efforts were unveiled in the Field Museum's Hall of Man in 1933.

More traditional portrait busts, which she executed throughout her career, include those of the pianist Ignace Paderewski, the sculptor Ivan Mestrovic, and the industrialist Henry Clay Frick. Examples of a number of these are in the collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Hoffman was an active participant in the New York art world. Her Sniffen Court studio became a salon of sorts for her many friends, among whom were Mestrovic, Paderewski, and the poet Marianne Moore. She exhibited at the Academy throughout her career; among her many awards were the Helen Foster Barnett Prize, which she won in 1921, and the Elizabeth N. Watrous Gold Medal, which she received in the winter of 1924 for a portrait of Pavlova. She was a member of the National Sculpture Society, New York. Among her three books was the historical and technical guide Sculpture Inside and Out (1939).

Hoffman made a generous monetary bequest to the Academy for the establishment of an annual prize in sculpture. She also left the Academy an assortment of casts and sculpting tools and materials.