No Image Available

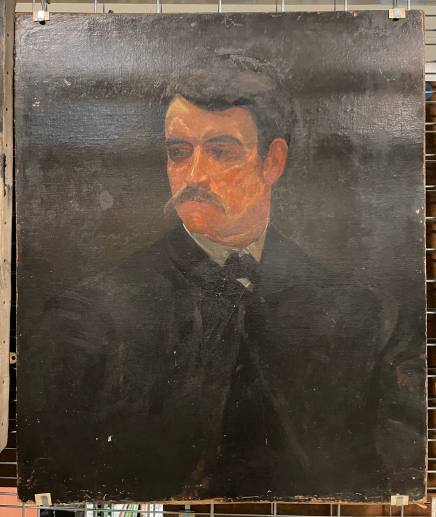

for John Cranch

American, 1807 - 1891

John Cranch, the third son of William Cranch and older brother of Christopher Pearse Cranch, also earned a degree from Columbian College in Washington, D.C.. At his commencement in 1826 he read the poem "Painting," which he had composed for the occasion; this suggests that he had determined on his career at an early age. According to William Dunlap, Cranch studied art under Chester Harding, Charles Bird King, and Thomas Sully. However Dunlap did not provide details about the dates and places of this study. All three artists were active in Washington at various times before 1829, when Cranch first advertised his services as a portraitist, and it is likely that an aspiring young painter-with the best of family backgrounds-would have sought out and received some attention from the senior artists who appeared in the city during those early years of its development.

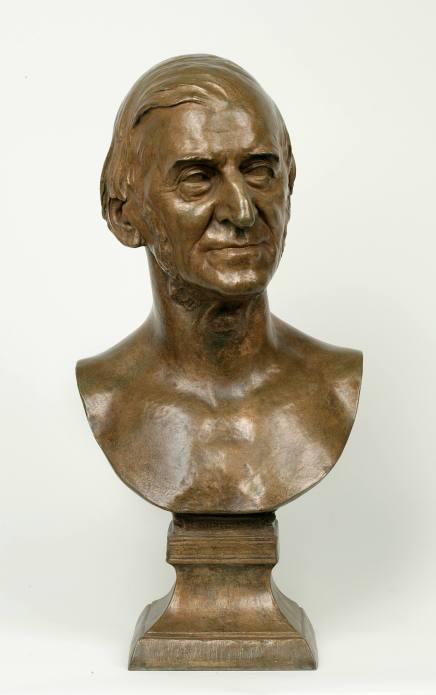

Cranch went to Italy in 1830, spending most of the four years he passed there in Florence and Venice. He formed a lasting friendship with the expatriate American sculptor Hiram Powers and enjoyed the company of visiting American friends such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. In addition to studying the Old Masters, Cranch painted portraits, genre scenes, and scenes from Shakespeare's plays. Upon returning to America in 1834, he settled in New York. It was not until 1838 that his work appeared in an Academy annual exhibition.

In 1839 Cranch became a follower of the Swedenborgian faith, based on the teachings of the Swedish scientist, philosopher, and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. The artists William Page and Hiram Powers also were drawn to this sect. Cranch was represented in that year's Academy annual by a portrait of a child, a study of an old man "painted at Rome," and a picture of great importance to him, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, which was inspired by the Twenty-third Psalm and meant to be inspirational. Only one reviewer, a writer for the New York Literary Gazette, noticed the painting. While admitting that it was "well-imagined," he observed that "the execution is inferior to the conception. Its faults . . . are obvious to the commonest apprehension; those rocks, like cakes of soap; . . . the ludicrous is not far removed from the terrible."

That autumn Cranch left New York for Cincinnati, Ohio. He was active in the art community there, serving as president of the Fine Arts Section of the Hamilton County Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. After marrying in 1845 he moved to Boston, exhibiting at the Boston Athenaeum the following year. In 1848 he was again in New York. From 1849 to 1852 his studio was in the New York University Building. In 1853 and 1854 he had a studio at 806 Broadway that he shared for the first year with his brother Christopher. In both these years he exhibited in the Academy annuals. But despite finally being elected to the Academy, his prospects must have seemed unpromising, for in 1855 he moved yet again-this time back to Washington, D.C.

There he soon became involved with the newly formed Washington Art Association, serving as a director and later as corresponding secretary. He exhibited at the National Academy for a final time in 1858 (again showing The Valley of the Shadow of Death). That year was also the last one in which he was listed as an artist in the Washington, D.C., city directory; thereafter his profession was given as "postal clerk." Cranch left Washington in 1878. Nothing is known of his whereabouts until about 1885, when he was again working as a portraitist in Urbana, Illinois. His son-in-law was serving president of Urbana University, the small Swedenborgian college there.

Despite the fact that Cranch's connections with the Academy were minimal and long in the past, the memorial entered into Council minutes on January 12, 1891, gently characterized him "as a frequent contributor to the Exhibitions of meritorious works in portrait and genre. . . . In temperament and critical knowledge he was an artist of the truest feeling and his personal life and character were singularly blameless and lovable."

Cranch went to Italy in 1830, spending most of the four years he passed there in Florence and Venice. He formed a lasting friendship with the expatriate American sculptor Hiram Powers and enjoyed the company of visiting American friends such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. In addition to studying the Old Masters, Cranch painted portraits, genre scenes, and scenes from Shakespeare's plays. Upon returning to America in 1834, he settled in New York. It was not until 1838 that his work appeared in an Academy annual exhibition.

In 1839 Cranch became a follower of the Swedenborgian faith, based on the teachings of the Swedish scientist, philosopher, and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. The artists William Page and Hiram Powers also were drawn to this sect. Cranch was represented in that year's Academy annual by a portrait of a child, a study of an old man "painted at Rome," and a picture of great importance to him, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, which was inspired by the Twenty-third Psalm and meant to be inspirational. Only one reviewer, a writer for the New York Literary Gazette, noticed the painting. While admitting that it was "well-imagined," he observed that "the execution is inferior to the conception. Its faults . . . are obvious to the commonest apprehension; those rocks, like cakes of soap; . . . the ludicrous is not far removed from the terrible."

That autumn Cranch left New York for Cincinnati, Ohio. He was active in the art community there, serving as president of the Fine Arts Section of the Hamilton County Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. After marrying in 1845 he moved to Boston, exhibiting at the Boston Athenaeum the following year. In 1848 he was again in New York. From 1849 to 1852 his studio was in the New York University Building. In 1853 and 1854 he had a studio at 806 Broadway that he shared for the first year with his brother Christopher. In both these years he exhibited in the Academy annuals. But despite finally being elected to the Academy, his prospects must have seemed unpromising, for in 1855 he moved yet again-this time back to Washington, D.C.

There he soon became involved with the newly formed Washington Art Association, serving as a director and later as corresponding secretary. He exhibited at the National Academy for a final time in 1858 (again showing The Valley of the Shadow of Death). That year was also the last one in which he was listed as an artist in the Washington, D.C., city directory; thereafter his profession was given as "postal clerk." Cranch left Washington in 1878. Nothing is known of his whereabouts until about 1885, when he was again working as a portraitist in Urbana, Illinois. His son-in-law was serving president of Urbana University, the small Swedenborgian college there.

Despite the fact that Cranch's connections with the Academy were minimal and long in the past, the memorial entered into Council minutes on January 12, 1891, gently characterized him "as a frequent contributor to the Exhibitions of meritorious works in portrait and genre. . . . In temperament and critical knowledge he was an artist of the truest feeling and his personal life and character were singularly blameless and lovable."