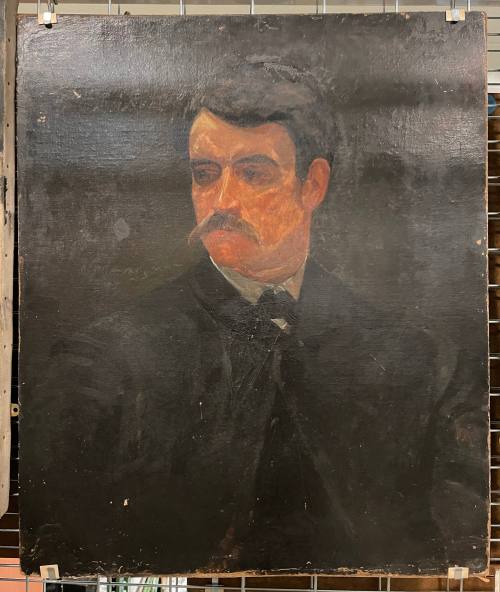

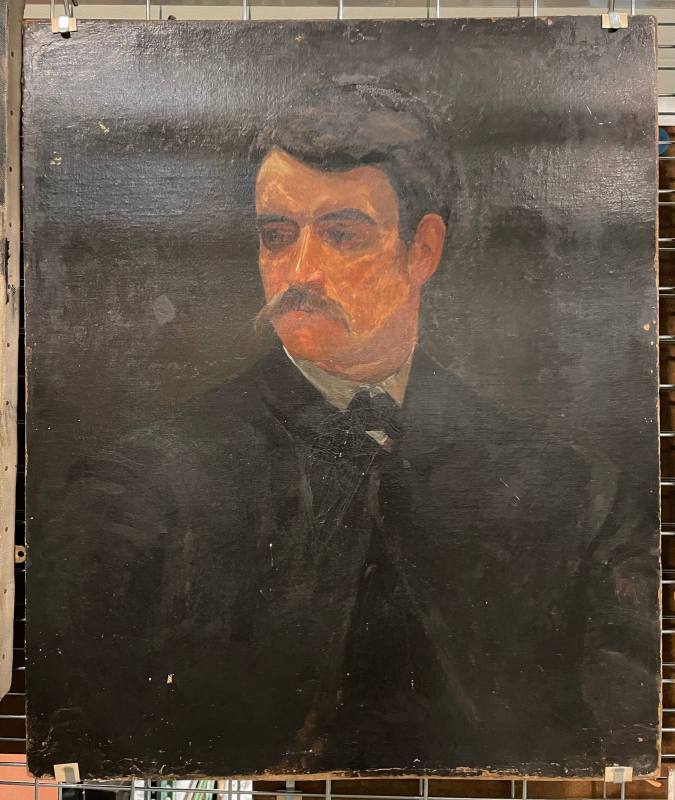

American, 1836 - 1910

Although Winslow Homer's father has been described as a well-to-do importer of hardware, it is difficult to link him to any steady employment following his return in 1851 from an unsuccessful venture in California. Homer's mother, a devoted amateur watercolorist, doubtless had the greater influence on his development. The family moved from Boston to the then-country town of Cambridge when Homer was six years old. He showed both interest and talent in art from childhood and was encouraged by his parents.

In 1855, when he was nineteen, he was apprenticed at John H. Bufford's, the dominant lithography firm in Boston. He worked there for two years, designing sheet-music covers and other popular illustrations. Homer hated the work. On his twenty-first birthday, February 24, 1857, when the apprenticeship contract expired, he left Bufford's, vowing never again to be anyone's employee. He immediately set up a studio and began working as a freelance illustrator. Over the next two years his designs, rendered into wood engravings by technicians, were seen in Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, published in Boston, and in the newly established New York periodical Harper's Weekly. In the autumn of 1859, having attained some little success, and some standing with Harper's, Homer moved to New York. He is said to have determined to become a painter while still an apprentice lithographer, and, since Boston lacked any opportunity for advanced training at the time, it is likely that New York's primary lure was the National Academy school.

Homer registered in the school for the 1859-60 academic season, being allowed the unusual privilege of entering the life class directly without first proving his attainments in the antique class. He registered again in the Academy's life class for 1860-61 and 1863-64 and received some private instruction in painting from Frederic Rondel in 1861. He simultaneously sustained his successful freelance-illustrating career. Harper's was his principal employer, but his work was seen in a number of popular periodicals. Ever practical about financial matters, Homer continued to assure his living through illustration until 1875, though his overriding intention was to become a painter.

Harper's had sent Homer to Washington, D.C., in the autumn of 1861 to report on General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac, which was encamped all around the city. However, in the spring of 1862, when McClellan finally embarked on a campaign to take Richmond, it was on his own initiative that Homer spent five weeks traveling with the army. He would again visit the front in the spring of 1864, but the 1862 experience was his most sustained exposure to military life, and it formed the subject of his first serious work in oil. Homer made his debut as a painter in the Academy's annual exhibition of 1863 with two Civil War subjects; the following year he showed two more war-related scenes. The annual exhibition of 1865 had special significance, as it inaugurated the Academy's impressive new building at Twenty-third Street and Fourth Avenue; Homer again was principally represented by scenes of army camp life, one being his most ambitious work up to that time, Pitching Quoits (1865, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Homer's career developed successfully over the next fifteen years. His subjects were genre scenes drawn from visits to popular eastern summer resorts in pursuit of subjects for his illustrations, and from summer vacations spent hunting and fishing in the Adirondacks and visiting friends on their farms in upstate New York. Other than the sporting pictures, his favored themes were children and young people as well as winsome young country and city women. A visit to France from late 1866 to the autumn of 1867 seemed to have no significant influence on the character of his work. A small group of paintings of blacks, based on probably just two visits to the South in 1876 and 1877, enjoyed particular critical success. In Gloucester, Massachusetts, during the summer of 1873, Homer began working in watercolor. Throughout the following years he would expand the supposed limitations of the medium in increasingly bold and colorful paintings.

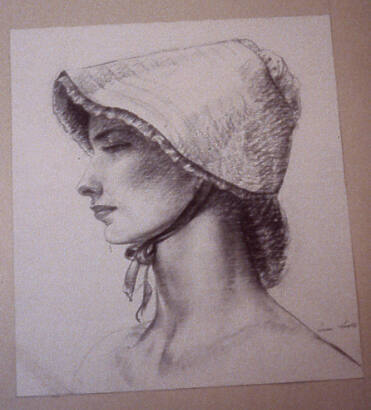

In the spring of 1881 Homer left New York for a two-year stay in England, settling in the small fishing village of Cullercoats on the northeastern coast. Unlike his previous sojourn abroad, this period of intense work, in which he used the stalwart fisherfolk as subjects, brought about a metamorphosis in his art. His figures became monumental, but more significantly, the expressive content of his paintings turned from the transitory moments of day-to-day life to the eternal tension between man and the elements-especially the dominating power of the sea over those who lived and worked in close relationship with it. He returned to New York in November 1882. Much of that winter was presumably occupied with completion of a major oil on a Cullercoats subject, The Coming Away of the Gale (1883/93, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts, as The Gale) for the Academy annual of 1883; it was not well received.

While he had been in England, Homer's brothers had begun to invest in land in Prout's Neck, Maine, intending to develop the community into a summer resort. Homer made his first extended stay in Prout's Neck in the summer of 1883. Also that summer he visited Atlantic City, New Jersey, to observe the well-known shipwreck-rescue teams operating there. Two major oil paintings were the result. The first to be completed was The Life Line (1884, Philadelphia Museum of Art), which, when shown in the Academy annual of 1884, reversed the previous year's negative reactions to Homer's newly powerful manner of painting. Catherine Lorillard Wolfe's purchase of The Life Line for the handsome sum of $2,500 during the exhibition-preview reception made headlines. The fact that Homer's painting was the first American work to enter Miss Wolfe's famous collection did not go unnoticed. (The second major oil to result from Homer's observations of the rescue operations was Undertow [1886, Stirling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts]; it was also a huge success when shown at the Academy in 1887.)

Homer's parents had been living in New York since the winter of 1872-73. Several weeks after his triumph at the 1884 Academy annual, his mother died. She was buried in Boston, and with his father Homer went on immediately to Prout's Neck. His father did not return to New York that autumn, thereafter spending winters in a Boston hotel and summers in Prout's Neck. Homer no longer needed to be in New York, either to advance his professional reputation or tend to family interests. He was now free to indulge what apparently was a deeply felt need to work in privacy and isolation. Although he visited New York and Boston frequently, starting in late 1884 Homer made his home in his Prout's Neck studio.

Over the next twenty-three years, until ill health diminished his capacity for work, Homer painted ever more monumental images of the sea and the men who earn their livings from it. Winter trips to Florida, the Caribbean, and Bermuda as well as summer and autumn hunting trips to the Adirondacks and Canada were the sources of a great body of fully mature watercolors. One of his most powerful images, The Gulf Stream (1899), came from his experience of the southern seas. This painting, first shown in 1899, was included in the Academy's winter exhibition of 1906. The jury took the extraordinary action of writing the Metropolitan Museum of Art, strongly advising it to purchase The Gulf Stream immediately, before the exhibition opened, when a private buyer might acquire the work. The Metropolitan did so, and the painting remains in its collection.

Homer's work was subtle and sophisticated in formal design and expressive content yet also accessible to a popular audience. By the end of the century he was arguably the nation's best-known and most highly respected artist. Internationally, as an American artist, his reputation was exceeded only by those of John Singer Sargent and James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

Until his return from England and withdrawal from New York and, thereby, from the accepted career arena of American artists, Homer pursued a fairly active role in the community of his peers. He had a studio in the New York University building from 1861 until early in 1872, when he moved to the Tenth Street Studio Building, the preeminent artists' address of that period. He remained there until shortly before his departure for England. Elected to membership in the Century Association in 1865, he was consistently represented in its monthly exhibitions and served a one-year term on its art committee in 1873. He did similar service with the Palette Club in 1874.

Late in 1869 the Academy planned a major change in the operation of its school by seeking a full-time supervising instructor; exploratory overtures were made to Homer and George Cochran Lambdin. Although it was reported to the Council that both men were willing to take the job, the painter Lemuel Wilmarth was hired. At the Academy's annual meeting of 1872 Homer was elected to the hanging committee for the following season, receiving the most votes of any of the candidates. At the next year's meeting he was elected to the Council for the 1873-74 term. He contributed to every Academy annual from 1863 through 1888, excepting only 1871; 1873, when he was a member of the hanging committee (the jury that selected and mounted the works in the exhibition); and 1881 and 1882, when he was in England. As the quantity of his oil paintings decreased and opportunities for them to be exhibited increased, his participation in Academy shows became less vital.

Homer died in September 1910. The Academy included five of his major canvases in its winter exhibition that opened that December. By the early twentieth century, the Academy had given up its practice of reading extensive eulogies on deceased members into the minutes at annual meetings. However, the Council's expression of respect, though succinct, exactly summarized Homer's achievement: "Resolved that in the death of Winslow Homer the National Academy of Design has lost one of its most honored members, America a National glory, and the World one of the most powerful and original artists of the Nineteenth Century."

In 1855, when he was nineteen, he was apprenticed at John H. Bufford's, the dominant lithography firm in Boston. He worked there for two years, designing sheet-music covers and other popular illustrations. Homer hated the work. On his twenty-first birthday, February 24, 1857, when the apprenticeship contract expired, he left Bufford's, vowing never again to be anyone's employee. He immediately set up a studio and began working as a freelance illustrator. Over the next two years his designs, rendered into wood engravings by technicians, were seen in Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, published in Boston, and in the newly established New York periodical Harper's Weekly. In the autumn of 1859, having attained some little success, and some standing with Harper's, Homer moved to New York. He is said to have determined to become a painter while still an apprentice lithographer, and, since Boston lacked any opportunity for advanced training at the time, it is likely that New York's primary lure was the National Academy school.

Homer registered in the school for the 1859-60 academic season, being allowed the unusual privilege of entering the life class directly without first proving his attainments in the antique class. He registered again in the Academy's life class for 1860-61 and 1863-64 and received some private instruction in painting from Frederic Rondel in 1861. He simultaneously sustained his successful freelance-illustrating career. Harper's was his principal employer, but his work was seen in a number of popular periodicals. Ever practical about financial matters, Homer continued to assure his living through illustration until 1875, though his overriding intention was to become a painter.

Harper's had sent Homer to Washington, D.C., in the autumn of 1861 to report on General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac, which was encamped all around the city. However, in the spring of 1862, when McClellan finally embarked on a campaign to take Richmond, it was on his own initiative that Homer spent five weeks traveling with the army. He would again visit the front in the spring of 1864, but the 1862 experience was his most sustained exposure to military life, and it formed the subject of his first serious work in oil. Homer made his debut as a painter in the Academy's annual exhibition of 1863 with two Civil War subjects; the following year he showed two more war-related scenes. The annual exhibition of 1865 had special significance, as it inaugurated the Academy's impressive new building at Twenty-third Street and Fourth Avenue; Homer again was principally represented by scenes of army camp life, one being his most ambitious work up to that time, Pitching Quoits (1865, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Homer's career developed successfully over the next fifteen years. His subjects were genre scenes drawn from visits to popular eastern summer resorts in pursuit of subjects for his illustrations, and from summer vacations spent hunting and fishing in the Adirondacks and visiting friends on their farms in upstate New York. Other than the sporting pictures, his favored themes were children and young people as well as winsome young country and city women. A visit to France from late 1866 to the autumn of 1867 seemed to have no significant influence on the character of his work. A small group of paintings of blacks, based on probably just two visits to the South in 1876 and 1877, enjoyed particular critical success. In Gloucester, Massachusetts, during the summer of 1873, Homer began working in watercolor. Throughout the following years he would expand the supposed limitations of the medium in increasingly bold and colorful paintings.

In the spring of 1881 Homer left New York for a two-year stay in England, settling in the small fishing village of Cullercoats on the northeastern coast. Unlike his previous sojourn abroad, this period of intense work, in which he used the stalwart fisherfolk as subjects, brought about a metamorphosis in his art. His figures became monumental, but more significantly, the expressive content of his paintings turned from the transitory moments of day-to-day life to the eternal tension between man and the elements-especially the dominating power of the sea over those who lived and worked in close relationship with it. He returned to New York in November 1882. Much of that winter was presumably occupied with completion of a major oil on a Cullercoats subject, The Coming Away of the Gale (1883/93, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts, as The Gale) for the Academy annual of 1883; it was not well received.

While he had been in England, Homer's brothers had begun to invest in land in Prout's Neck, Maine, intending to develop the community into a summer resort. Homer made his first extended stay in Prout's Neck in the summer of 1883. Also that summer he visited Atlantic City, New Jersey, to observe the well-known shipwreck-rescue teams operating there. Two major oil paintings were the result. The first to be completed was The Life Line (1884, Philadelphia Museum of Art), which, when shown in the Academy annual of 1884, reversed the previous year's negative reactions to Homer's newly powerful manner of painting. Catherine Lorillard Wolfe's purchase of The Life Line for the handsome sum of $2,500 during the exhibition-preview reception made headlines. The fact that Homer's painting was the first American work to enter Miss Wolfe's famous collection did not go unnoticed. (The second major oil to result from Homer's observations of the rescue operations was Undertow [1886, Stirling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts]; it was also a huge success when shown at the Academy in 1887.)

Homer's parents had been living in New York since the winter of 1872-73. Several weeks after his triumph at the 1884 Academy annual, his mother died. She was buried in Boston, and with his father Homer went on immediately to Prout's Neck. His father did not return to New York that autumn, thereafter spending winters in a Boston hotel and summers in Prout's Neck. Homer no longer needed to be in New York, either to advance his professional reputation or tend to family interests. He was now free to indulge what apparently was a deeply felt need to work in privacy and isolation. Although he visited New York and Boston frequently, starting in late 1884 Homer made his home in his Prout's Neck studio.

Over the next twenty-three years, until ill health diminished his capacity for work, Homer painted ever more monumental images of the sea and the men who earn their livings from it. Winter trips to Florida, the Caribbean, and Bermuda as well as summer and autumn hunting trips to the Adirondacks and Canada were the sources of a great body of fully mature watercolors. One of his most powerful images, The Gulf Stream (1899), came from his experience of the southern seas. This painting, first shown in 1899, was included in the Academy's winter exhibition of 1906. The jury took the extraordinary action of writing the Metropolitan Museum of Art, strongly advising it to purchase The Gulf Stream immediately, before the exhibition opened, when a private buyer might acquire the work. The Metropolitan did so, and the painting remains in its collection.

Homer's work was subtle and sophisticated in formal design and expressive content yet also accessible to a popular audience. By the end of the century he was arguably the nation's best-known and most highly respected artist. Internationally, as an American artist, his reputation was exceeded only by those of John Singer Sargent and James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

Until his return from England and withdrawal from New York and, thereby, from the accepted career arena of American artists, Homer pursued a fairly active role in the community of his peers. He had a studio in the New York University building from 1861 until early in 1872, when he moved to the Tenth Street Studio Building, the preeminent artists' address of that period. He remained there until shortly before his departure for England. Elected to membership in the Century Association in 1865, he was consistently represented in its monthly exhibitions and served a one-year term on its art committee in 1873. He did similar service with the Palette Club in 1874.

Late in 1869 the Academy planned a major change in the operation of its school by seeking a full-time supervising instructor; exploratory overtures were made to Homer and George Cochran Lambdin. Although it was reported to the Council that both men were willing to take the job, the painter Lemuel Wilmarth was hired. At the Academy's annual meeting of 1872 Homer was elected to the hanging committee for the following season, receiving the most votes of any of the candidates. At the next year's meeting he was elected to the Council for the 1873-74 term. He contributed to every Academy annual from 1863 through 1888, excepting only 1871; 1873, when he was a member of the hanging committee (the jury that selected and mounted the works in the exhibition); and 1881 and 1882, when he was in England. As the quantity of his oil paintings decreased and opportunities for them to be exhibited increased, his participation in Academy shows became less vital.

Homer died in September 1910. The Academy included five of his major canvases in its winter exhibition that opened that December. By the early twentieth century, the Academy had given up its practice of reading extensive eulogies on deceased members into the minutes at annual meetings. However, the Council's expression of respect, though succinct, exactly summarized Homer's achievement: "Resolved that in the death of Winslow Homer the National Academy of Design has lost one of its most honored members, America a National glory, and the World one of the most powerful and original artists of the Nineteenth Century."