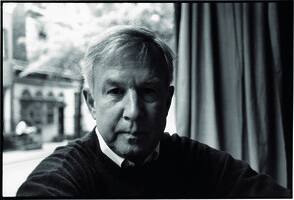

American, 1893 - 1959

Grosz pursued classical art study at the Royal Saxon Academy of the Fine Arts in Dresden, Germany, from 1909 to 1912, when he continued his training at the Royal Arts and Crafts School, Berlin, which he attended, intermittantly into 1916. By 1910, however, he was selling his topical drawings to German humor magazines. He had already been introduced to modernist art by an exhibition of Italian Futurist art seen in Berlin by 1913 when he was in Paris for six months' study at the Academie Colarossi. The ferment of new art movements experienced there reinforced his inclination to rebellion against his traditional training.

Grosz served as a common soldier in the German army in World War I from 1914 to early 1916, and again in 1917-18. The experience unleashed his fierce rejection of contemporary life and the values on which it was based. Initially he expressed his disillusion through the artistic philosophy of Dada, and was a founder of the Berlin Dada movement. He soon turned away from the nihilism of Dada to an active, especially virulent attack on the depravity of post-war German society, and then the evil evidence of fascism through his satiric drawings--drawings, which even in their Bosch-like distortions of the human figure, revealed his thorough academic training. Grosz was three times arrested as a menace to the established order, yet his work only became more aggressive in its ruthless exposure of the sickness in the German state. Thirteen volumes of his drawings were published in these years, the most famous being the suppressed Ecce Homo of 1923.

In 1931 Grosz received the Watson F. Blair prize of the Art Institute of Chicago annual exhibition; his first American one-man show, including watercolors and drawings was presented at the Weyhe Gallery in New York, the same year. The following year, at the invitation of John Sloan, he came to New York to teach at the Art Students League. After a brief return to Germany in 1933, he returned to America, bringing his family to establish permanent residence. Grosz became an American citizen in 1938.

In New York in 1933 he founded, with Maurice Sterne,the Sterne-Grosz School, which continued, without Sterne, to 1937. Grosz continued to teach at the Art Students League to 1936, rejoining its faculty for the seasons of 1940-42, 1943-44, and 1950-55. In America, Grosz's artistic expression inevitably was considerably altered. Working in oil and watercolor, he turned to more conventional subjects, especially related to his summer stays on Massachusetts's Cape Cod in the 1940s. In these years an alternate to his classical nudes in the Cape Cod dunes were dark, fearsome images on the universal theme of war and death.

Paintings by Grosz were awarded the Carlo H. Beck Medal by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and another Blair Prize by the Art Institute of Chicago, both in 1940. In 1945 he received a second prize in the Carnegie Art Institute, Pittsburgh, International.

In the 1950s Grosz began visiting Europe: Switzerland, Italy France, Holland, and in Germany, Munich and Berlin. He designed costumes for a Berlin theatrical production in 1954; in 1958 he was elected to the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts. In the spring of 1959 Grosz returned to Berlin to live, saying "every stone, every house and every tree in Berlin makes me feel at home." He died three months later.

Grosz served as a common soldier in the German army in World War I from 1914 to early 1916, and again in 1917-18. The experience unleashed his fierce rejection of contemporary life and the values on which it was based. Initially he expressed his disillusion through the artistic philosophy of Dada, and was a founder of the Berlin Dada movement. He soon turned away from the nihilism of Dada to an active, especially virulent attack on the depravity of post-war German society, and then the evil evidence of fascism through his satiric drawings--drawings, which even in their Bosch-like distortions of the human figure, revealed his thorough academic training. Grosz was three times arrested as a menace to the established order, yet his work only became more aggressive in its ruthless exposure of the sickness in the German state. Thirteen volumes of his drawings were published in these years, the most famous being the suppressed Ecce Homo of 1923.

In 1931 Grosz received the Watson F. Blair prize of the Art Institute of Chicago annual exhibition; his first American one-man show, including watercolors and drawings was presented at the Weyhe Gallery in New York, the same year. The following year, at the invitation of John Sloan, he came to New York to teach at the Art Students League. After a brief return to Germany in 1933, he returned to America, bringing his family to establish permanent residence. Grosz became an American citizen in 1938.

In New York in 1933 he founded, with Maurice Sterne,the Sterne-Grosz School, which continued, without Sterne, to 1937. Grosz continued to teach at the Art Students League to 1936, rejoining its faculty for the seasons of 1940-42, 1943-44, and 1950-55. In America, Grosz's artistic expression inevitably was considerably altered. Working in oil and watercolor, he turned to more conventional subjects, especially related to his summer stays on Massachusetts's Cape Cod in the 1940s. In these years an alternate to his classical nudes in the Cape Cod dunes were dark, fearsome images on the universal theme of war and death.

Paintings by Grosz were awarded the Carlo H. Beck Medal by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and another Blair Prize by the Art Institute of Chicago, both in 1940. In 1945 he received a second prize in the Carnegie Art Institute, Pittsburgh, International.

In the 1950s Grosz began visiting Europe: Switzerland, Italy France, Holland, and in Germany, Munich and Berlin. He designed costumes for a Berlin theatrical production in 1954; in 1958 he was elected to the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts. In the spring of 1959 Grosz returned to Berlin to live, saying "every stone, every house and every tree in Berlin makes me feel at home." He died three months later.