1885 - 1966

Manship began his career as an illustrator or painter but, on discovering that he was color-blind, turned to sculpting. He studied both painting and sculpture at the Saint Paul Institute School of Art from 1892 to 1903. After a period of work as a designer and illustrator in Saint Paul, he went East in 1905 to continue his training, first at the Art Students League, New York, and then, beginning in 1907, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, where he studied under Charles Grafly. According to his son, John, Manship was influenced during these years by the work of Solon Borglum for whom he served as assistant in New York. After a brief trip to Spain in the summer of 1908, he returned to New York to work in the studio of Isidore Konti who encouraged him to apply for a scholarship to the American Academy in Rome, an honor he won in 1909. His going to Rome instead of Paris was responsible for Manship's introduction to classical art which was to have a lasting influence on his art.

Manship returned to New York in 1912, and enjoyed immediate professional success. He became friends with the painter John LaFarge and the sculptor Daniel Chester French, both of whom helped Manship get commissions, and he was given several important exhibitions, notably that held at the Architectural League in 1913. Two years later, forty of his sculptures made a tour of major museums throughout the country, and in 1916 a large collection of his casts was shown at the Berlin Photographic Company, New York. Meanwhile, major American museums began to acquire his works. The Metropolitan Museum acquired the Centaur and Dryad in 1914, and in 1916, a portrait of Pauline Frances Manship, daughter of the sculptor and his wife, Isabel McIlwaine, whom he had married in 1913. Among important commissions awarded to Manship during these years were several from architects. For Grant La Farge he executed sculptures for the Blessed Sacrament Church, Providence, Rhode Island; for Welles Bosworth, a number of works for the American Telephone and Telegraph Building, New York; and many garden sculptures for Charles Platt.

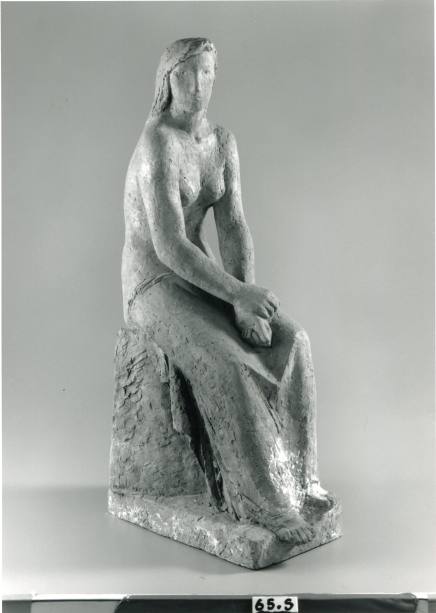

Following World War I, during which Manship served with the Red Cross in Italy, he and his family lived in London and then in Paris, returning to the United States in 1927. Many of his best known works date from these years, works such as the Diana and Actaeon, 1925, and Indian Hunter and His Dog, 1926, both of which reflect the artist's gift for transforming classical motifs into a modernist idiom. Manship also received a large number of major commissions during the years between the wars and kept studios in both New York and Paris to handle the work. Among the most monumental, as well as widely recognized of Manship's commissions in this period are the decorative scheme for the western terminus of Rockefeller Center Plaza, centered on the Prometheus, 1934; and sculptures for the 1939 New York World's Fair.

The situation changed, however, following World War II, when critical appreciation of Manship's work lessened. Some important commissions nevertheless continued to come to him: a statue of John Hancock in 1948, and of Theodore Roosevelt in 1967, both for Boston, and an armillary sphere for the New York World's Fair of 1964. His creative powers did not retreat as his age advanced and he remained an active and interesting artist until his death at the age of eighty.

Manship first exhibited at the Academy in 1907 and continued to do so sporadically into the 1960s. Two of his most successful early works received the Academy's Helen Foster Barnett Prize, Centaur and Dryad in the winter exhibition of 1913, and Dancer and Gazelles in the winter exhibition of 1917. In the annual exhibition of 1963, he was award the Academy's Saltus Medal.

Awards, honors, and professional acknowledgment came early and in quantity to Manship. Along with the great volume of his sculptural work, he undertook an exceptional range of administrative responsibilities in organizations in which he might have remained simply a member. From 1939 to 1942 he served as president of the National Sculpture Society; elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1920, and to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1932, he served as president of the latter from 1948 to 1952; from 1942 to 1948, as second vice president of the National Academy, he was a member of it Council; from 1950 to 1954 he was president of New York's Century Association; and from 1936 to 1966 he chaired the Smithsonian Institution's Fine Arts Commission, the oversight body of the National Collection of Fine Arts (now National Museum of American Art).

According to Manship's wishes, at his death the contents of his studio were divided between the National Museum of American Art, and the museum of his native city, the Minnesota Museum of Art.

In 1913 when he was vice president of the Academy, Herbert Adams in a letter to Grant La Farge, essentially recommending the technical and aesthetic excellence of the young Manship's work about to be shown in the winter exhibition, aptly predicted his future: "It seems to me that here is a man who, if given a chance to work out his natural bent, may do American art an incalcuable good."

Manship returned to New York in 1912, and enjoyed immediate professional success. He became friends with the painter John LaFarge and the sculptor Daniel Chester French, both of whom helped Manship get commissions, and he was given several important exhibitions, notably that held at the Architectural League in 1913. Two years later, forty of his sculptures made a tour of major museums throughout the country, and in 1916 a large collection of his casts was shown at the Berlin Photographic Company, New York. Meanwhile, major American museums began to acquire his works. The Metropolitan Museum acquired the Centaur and Dryad in 1914, and in 1916, a portrait of Pauline Frances Manship, daughter of the sculptor and his wife, Isabel McIlwaine, whom he had married in 1913. Among important commissions awarded to Manship during these years were several from architects. For Grant La Farge he executed sculptures for the Blessed Sacrament Church, Providence, Rhode Island; for Welles Bosworth, a number of works for the American Telephone and Telegraph Building, New York; and many garden sculptures for Charles Platt.

Following World War I, during which Manship served with the Red Cross in Italy, he and his family lived in London and then in Paris, returning to the United States in 1927. Many of his best known works date from these years, works such as the Diana and Actaeon, 1925, and Indian Hunter and His Dog, 1926, both of which reflect the artist's gift for transforming classical motifs into a modernist idiom. Manship also received a large number of major commissions during the years between the wars and kept studios in both New York and Paris to handle the work. Among the most monumental, as well as widely recognized of Manship's commissions in this period are the decorative scheme for the western terminus of Rockefeller Center Plaza, centered on the Prometheus, 1934; and sculptures for the 1939 New York World's Fair.

The situation changed, however, following World War II, when critical appreciation of Manship's work lessened. Some important commissions nevertheless continued to come to him: a statue of John Hancock in 1948, and of Theodore Roosevelt in 1967, both for Boston, and an armillary sphere for the New York World's Fair of 1964. His creative powers did not retreat as his age advanced and he remained an active and interesting artist until his death at the age of eighty.

Manship first exhibited at the Academy in 1907 and continued to do so sporadically into the 1960s. Two of his most successful early works received the Academy's Helen Foster Barnett Prize, Centaur and Dryad in the winter exhibition of 1913, and Dancer and Gazelles in the winter exhibition of 1917. In the annual exhibition of 1963, he was award the Academy's Saltus Medal.

Awards, honors, and professional acknowledgment came early and in quantity to Manship. Along with the great volume of his sculptural work, he undertook an exceptional range of administrative responsibilities in organizations in which he might have remained simply a member. From 1939 to 1942 he served as president of the National Sculpture Society; elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1920, and to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1932, he served as president of the latter from 1948 to 1952; from 1942 to 1948, as second vice president of the National Academy, he was a member of it Council; from 1950 to 1954 he was president of New York's Century Association; and from 1936 to 1966 he chaired the Smithsonian Institution's Fine Arts Commission, the oversight body of the National Collection of Fine Arts (now National Museum of American Art).

According to Manship's wishes, at his death the contents of his studio were divided between the National Museum of American Art, and the museum of his native city, the Minnesota Museum of Art.

In 1913 when he was vice president of the Academy, Herbert Adams in a letter to Grant La Farge, essentially recommending the technical and aesthetic excellence of the young Manship's work about to be shown in the winter exhibition, aptly predicted his future: "It seems to me that here is a man who, if given a chance to work out his natural bent, may do American art an incalcuable good."