American, b. 1948

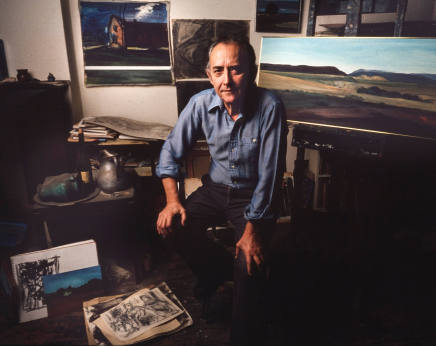

Judith Shea has been a notable presence in the New York art world since the 1970s. Trained as a designer at Parsons, she soon found the fashion industry too restrictive and abandoned it in favor of making art. Her early work referenced clothing and its construction, first as flat, minimalist pattern and later as molded draping over implied, absent figures.

In the 1981 Whitney Biennial, Shea showed three simple forms that evoked iconic clothes of the 1950s and 60s—the overcoat and the simple sheath dress—which hung from the wall as if on hangers. These works evoke human presence, felt as absence, as if the clothes were placeholders for missing persons. Thinking about her earlier clothes-based works, Shea has said that she “was looking for characters, for personae, really, to occupy them. I used clothes as stand-ins for people.”

With the support of NEA grants, Shea began to learn bronze casting, and she was able to also spend time in Paris studying the statuary of its parks and gardens. This research led to several hollow-figure compositions from the 1980s that were designed to be sited in public spaces. In the 1990s, after a residency at Chesterwood—the site of Daniel Chester French’s studio in Stockbridge—Shea began to use woodcarving to make monumental public sculpture.

Following several periods abroad, including in Bellagio as a Rockefeller Foundation Resident, in Rome as a Fellow at the American Academy, and in Oaxaca as a winner of the Lila Wallace–Reader’s Digest Artist’s Award, Shea began a group of works in 2000 that deal with the figure imagined as character and icon. This work set the stage for the evolution of her next major body of work, which she titled Judith Shea: Legacy Collection. The direct source of the Legacy Collection was the artist’s experience of 9/11: Shea’s home was, and still is, near Ground Zero. In this very personal response, Shea fashioned a group of mannequin-like figures looking skyward, elegant in gray felt, dusted by debris.

Shea is the recipient of numerous fellowships and awards; recent honors include the Anonymous Was a Woman Award, in 2011, and the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, in 2012.

In the 1981 Whitney Biennial, Shea showed three simple forms that evoked iconic clothes of the 1950s and 60s—the overcoat and the simple sheath dress—which hung from the wall as if on hangers. These works evoke human presence, felt as absence, as if the clothes were placeholders for missing persons. Thinking about her earlier clothes-based works, Shea has said that she “was looking for characters, for personae, really, to occupy them. I used clothes as stand-ins for people.”

With the support of NEA grants, Shea began to learn bronze casting, and she was able to also spend time in Paris studying the statuary of its parks and gardens. This research led to several hollow-figure compositions from the 1980s that were designed to be sited in public spaces. In the 1990s, after a residency at Chesterwood—the site of Daniel Chester French’s studio in Stockbridge—Shea began to use woodcarving to make monumental public sculpture.

Following several periods abroad, including in Bellagio as a Rockefeller Foundation Resident, in Rome as a Fellow at the American Academy, and in Oaxaca as a winner of the Lila Wallace–Reader’s Digest Artist’s Award, Shea began a group of works in 2000 that deal with the figure imagined as character and icon. This work set the stage for the evolution of her next major body of work, which she titled Judith Shea: Legacy Collection. The direct source of the Legacy Collection was the artist’s experience of 9/11: Shea’s home was, and still is, near Ground Zero. In this very personal response, Shea fashioned a group of mannequin-like figures looking skyward, elegant in gray felt, dusted by debris.

Shea is the recipient of numerous fellowships and awards; recent honors include the Anonymous Was a Woman Award, in 2011, and the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, in 2012.