American, 1848 - 1907

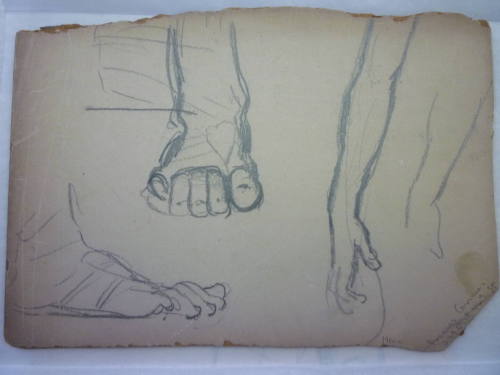

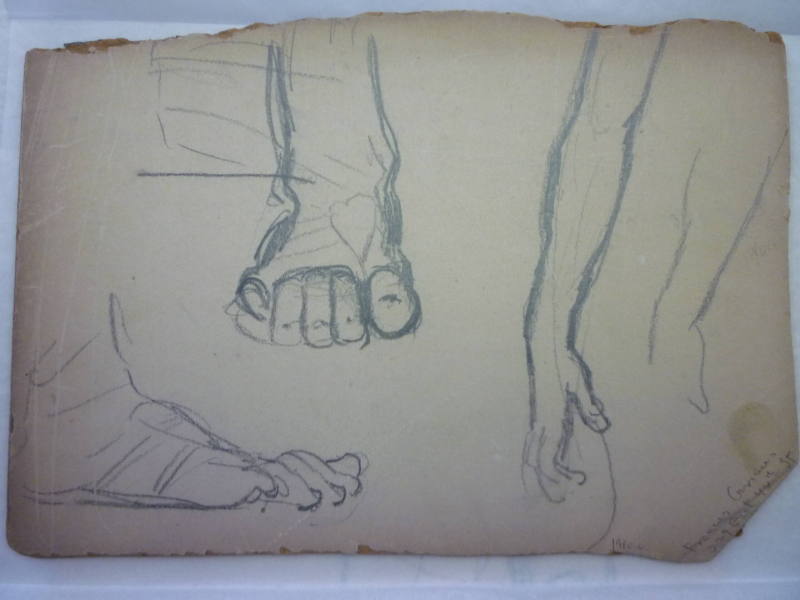

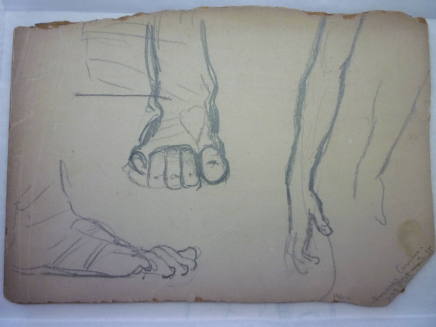

Saint-Gaudens was not a year old when his parents emigrated to America. He was raised and educated in New York. He was first apprenticed to Louis Avet, a cameo cutter, in 1861, but several years later changed apprentice masters, but not craft, joining Jules Le Brethon. He attended the Academy school's antique class from 1863 to 1867, and its life class in 1866 and 1867, and recalled these years in his reminiscences:

Shortly after beginning with Le Brethon, I also entered the National Academy of Design, the picturesque Italian Doge's palace on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Twenty-third Street. . . . This studying in the Academy at nights was very dream-like and in the surrounding quiet, broken only by the little shrill whistle of an ill-burning gas jet, I first felt my God-like indifference and scorn of all other would-be artists. Here too, came my appreciation of the antique and my earliest attempts to draw from the nude with the advise of Mr. Huntington and Mr. Leutze. . . .

The young sculptor went to Paris in 1867 and studied at the Petit Ecole, and in the atelier of Francois Jouffroy. In 1870 he went to Rome where he began to work independently. With the exception of about a year bridging 1872-73 spent in New York, Saint-Gaudens remained in Rome into 1875, and it was in Rome that he received his first commissions from Americans. On his return to New York in the early spring of 1875, he met John La Farge, the painter, and architects, Stanford White and Charles McKim. The careers of the four would be linked for a number of years in friendship as well as in jointly conceived and executed projects, among which were: Trinity Church, Boston; the Boston Public Library; and the creation of the Columbian Exposition's "White City" in Chicago. In 1875 Saint-Gaudens worked for Tiffany Studios, and showed for the first time in an Academy annual exhibition. The next year he received his first major public commission, the monument to Admiral David Farragut for Madison Square in New York, which established his reputation when unveiled in 1881. Over the remaining twenty-five years of his life the importance of his commissions, as well as the creativity, grace, and power with which he fulfilled them, would steadily increase; his fame and honors grew in proportion.

In 1877, when he next submitted for the Academy annual, the jury rejected his work. As an exemplar of the new generation of French-trained artists he was not alone in finding less than a warm welcome at America's preeminent, but conservative, exhibition event. The most conspicuous response to the situation was the founding, with Saint-Gaudens's active participation, of the Society of American Artists. Past experience, and his active role in the Society's operation--he was its president in 1881--may have had some bearing on his absence from Academy exhibitions, however, it could just as well have reflected the difficulty of so thoroughly employed an artist as Saint-Gaudens, finding the time to prepare new and unique work for both the Academy's and the Society's annual shows. The only further instances of Saint Gaudens exhibiting in Academy annuals were 1888 and 1889, that is, the years coinciding with his elections to membership. Considering the Academy rule limiting nominations to membership to current exhibitors, this suggests some unofficial maneuvering, and a desire held mutually by artist and Academy that he be counted in their number.

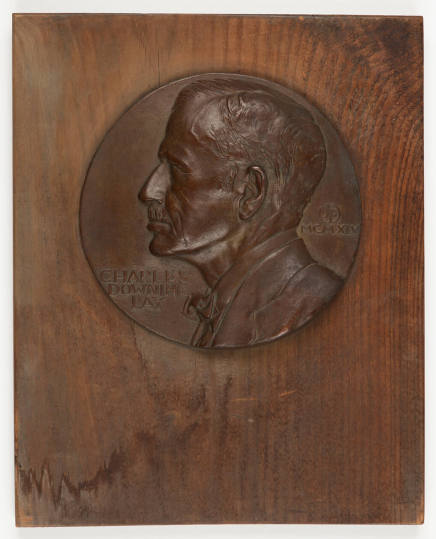

Saint-Gaudens was arguably America's most significant and most celebrated sculptor of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. From medals to the monumental his works set the American standard. Among his most well-known are the relief Robert Gould Shaw Memorial for the Boston Common, 1884-97; the allegorical figure on the grave of Marion Hooper, wife of Henry Adams, in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, 1886-91; the Diana, 1892-94 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), which once graced the top of the old Madison Square Garden, New York; and the William Tecumseh Sherman monument in Grand Army Plaza, New York, 1892-1903. Saint-Gaudens's infulence on contemporary art and artists was tremendous, primarily by the example of his works, but also as a teacher at the Art Students League, 1888-97, and as a founder of the National Sculture Society in 1893, and of the American Academy in Rome, in 1897.

Despite his early rebellion against the Academy, Saint-Gaudens's death brought a warm tribute from the Academy's president, Frederick Dielman, to be recorded in minutes:

His death, at an age when it might reasonably have been thought that he had many years before him to add to the noble sequence of works, by which he had won a position at the head of his profession in this country, and a notable place among the sculptors of the world and of all time, creates a void in the ranks of the National Academy of Design which the future alone may hope to repair. . . . The loss of the man, who in all his personal relations with his fellow-artists, was as modest and fraternal as his art was unusual and distinguished, is peculiarly our own and its sorrow can only be lightened by the memory of the privilege of his presence, and the pride of association with the maker of his noble work.

During his long and courageous struggle against relentless physical ills in the last decade, his artistic fire has never burned less brightly and, working to the last, his example is one by which all artists may profit. . . .

In 1885 Saint-Gaudens began summering in Cornish, New Hampshire, the center of an especially sophisticated summer colony of artist, writers and intellectuals. He purchased a substantial home there in 1891, and in 1900 established his studio on his extensive grounds. The property, with the studio and many models and examples of his sculpture became the Saint-Gaudens Memorial Trust, and is operated by the United States National Park Service.

Shortly after beginning with Le Brethon, I also entered the National Academy of Design, the picturesque Italian Doge's palace on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Twenty-third Street. . . . This studying in the Academy at nights was very dream-like and in the surrounding quiet, broken only by the little shrill whistle of an ill-burning gas jet, I first felt my God-like indifference and scorn of all other would-be artists. Here too, came my appreciation of the antique and my earliest attempts to draw from the nude with the advise of Mr. Huntington and Mr. Leutze. . . .

The young sculptor went to Paris in 1867 and studied at the Petit Ecole, and in the atelier of Francois Jouffroy. In 1870 he went to Rome where he began to work independently. With the exception of about a year bridging 1872-73 spent in New York, Saint-Gaudens remained in Rome into 1875, and it was in Rome that he received his first commissions from Americans. On his return to New York in the early spring of 1875, he met John La Farge, the painter, and architects, Stanford White and Charles McKim. The careers of the four would be linked for a number of years in friendship as well as in jointly conceived and executed projects, among which were: Trinity Church, Boston; the Boston Public Library; and the creation of the Columbian Exposition's "White City" in Chicago. In 1875 Saint-Gaudens worked for Tiffany Studios, and showed for the first time in an Academy annual exhibition. The next year he received his first major public commission, the monument to Admiral David Farragut for Madison Square in New York, which established his reputation when unveiled in 1881. Over the remaining twenty-five years of his life the importance of his commissions, as well as the creativity, grace, and power with which he fulfilled them, would steadily increase; his fame and honors grew in proportion.

In 1877, when he next submitted for the Academy annual, the jury rejected his work. As an exemplar of the new generation of French-trained artists he was not alone in finding less than a warm welcome at America's preeminent, but conservative, exhibition event. The most conspicuous response to the situation was the founding, with Saint-Gaudens's active participation, of the Society of American Artists. Past experience, and his active role in the Society's operation--he was its president in 1881--may have had some bearing on his absence from Academy exhibitions, however, it could just as well have reflected the difficulty of so thoroughly employed an artist as Saint-Gaudens, finding the time to prepare new and unique work for both the Academy's and the Society's annual shows. The only further instances of Saint Gaudens exhibiting in Academy annuals were 1888 and 1889, that is, the years coinciding with his elections to membership. Considering the Academy rule limiting nominations to membership to current exhibitors, this suggests some unofficial maneuvering, and a desire held mutually by artist and Academy that he be counted in their number.

Saint-Gaudens was arguably America's most significant and most celebrated sculptor of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. From medals to the monumental his works set the American standard. Among his most well-known are the relief Robert Gould Shaw Memorial for the Boston Common, 1884-97; the allegorical figure on the grave of Marion Hooper, wife of Henry Adams, in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, 1886-91; the Diana, 1892-94 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), which once graced the top of the old Madison Square Garden, New York; and the William Tecumseh Sherman monument in Grand Army Plaza, New York, 1892-1903. Saint-Gaudens's infulence on contemporary art and artists was tremendous, primarily by the example of his works, but also as a teacher at the Art Students League, 1888-97, and as a founder of the National Sculture Society in 1893, and of the American Academy in Rome, in 1897.

Despite his early rebellion against the Academy, Saint-Gaudens's death brought a warm tribute from the Academy's president, Frederick Dielman, to be recorded in minutes:

His death, at an age when it might reasonably have been thought that he had many years before him to add to the noble sequence of works, by which he had won a position at the head of his profession in this country, and a notable place among the sculptors of the world and of all time, creates a void in the ranks of the National Academy of Design which the future alone may hope to repair. . . . The loss of the man, who in all his personal relations with his fellow-artists, was as modest and fraternal as his art was unusual and distinguished, is peculiarly our own and its sorrow can only be lightened by the memory of the privilege of his presence, and the pride of association with the maker of his noble work.

During his long and courageous struggle against relentless physical ills in the last decade, his artistic fire has never burned less brightly and, working to the last, his example is one by which all artists may profit. . . .

In 1885 Saint-Gaudens began summering in Cornish, New Hampshire, the center of an especially sophisticated summer colony of artist, writers and intellectuals. He purchased a substantial home there in 1891, and in 1900 established his studio on his extensive grounds. The property, with the studio and many models and examples of his sculpture became the Saint-Gaudens Memorial Trust, and is operated by the United States National Park Service.