American, 1825 - 1888

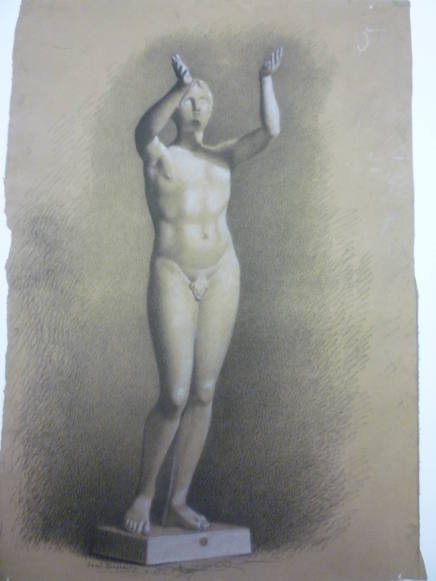

When Vincent Colyer was only seven his father died of cholera. As a result he spent much of his youth working as an errand-boy in order to help support his impoverished family. His duties, however, did not suppress his interests in art. In 1844, acting on the advice of the artist Edward Mooney, he began studying drawing under John Rubens Smith. These studies led to his admission in 1846 to the Academy antique class. He attended the class for three years. In 1848-49 he was in the life class as well, and he spent his fourth and final year in the school in the life class only. He first exhibited portrait drawings in an Academy annual exhibition in 1848 and remained a near-constant exhibitor. The only extended absence of his work was from 1868 through 1872. Colyer achieved a strong reputation for his likenesses, and even his crayon portraits were in demand.

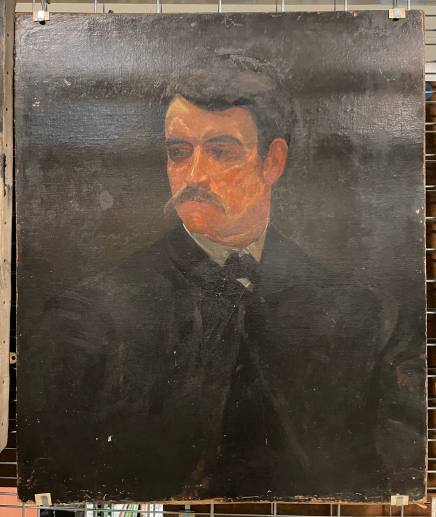

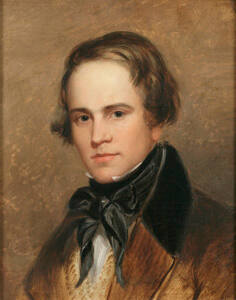

Colyer was initially elected an Associate in 1849 but did not qualify. That is, he did not submit a diploma portrait within a year of being elected. In May 1850, when his year had already expired, he notified the Council specifically declining the election, apparently because the hanging committee for that year's annual exhibition had failed to find room for drawings of his that the jury had accepted. His resentment over this incident seems not to have abated by the time he was again elected an Associate, at the annual meeting of 1851; this point was somehow made to the Council, for in April 1852 it entered a resolution of apology to "Mr. Colyer and his Friends" into the minutes. Once this resolution was communicated to the artist, he replied graciously, accepting his election and offering as his diploma presentation the portrait of him by Thomas Hicks then on view in the annual exhibition. A month later, at its annual meeting, the Academy made a further gesture of conciliation-and perhaps laid

groundwork for teaching Colyer a lesson in tolerance-by naming him to the hanging committee for the annual exhibition of 1853.

Throughout his life Colyer was a committed citizen. During the Civil War he nursed the ill and wounded, representing the New York YMCA, of which he was later president. His service generally stemmed from the philanthropic impulse to assist the unfortunate; thus it is not surprising that he was instrumental in the founding of the Artists' Fund Society in 1859 and was its first secretary. He also proved an effective politician. His dedication to public service and apparent facility with the ways of legislatures probably prompted the Council to send him in the spring of 1866 to Albany to lobby on behalf of a bill to secure tax-exempt status for the Academy; the measure passed.

In 1866 Colyer established residence near Darien, Connecticut, though he maintained a New York studio for approximately the next ten years. In the late 1860s he was elected to the Connecticut legislature. In the post-Civil War years, too, he served on the U.S. Indian Commission. This work took him frequently to the West, notably to Alaska, where he carefully recorded the landscape in his work.

These demands on Colyer's time and attention surely explain why he did not submit paintings to Academy annuals in the late 1860s and early 1870s. It is also likely that his residence outside New York, frequent extended travels, and compelling extra-artistic preoccupations collectively account for the fact that he did not advance to Academician. However, there may have been another contributing factor. In response to a general appeal the Council made to members in 1874 to give the Academy greater support-especially in helping ensure the quality of submissions to the exhibitions-Colyer organized a gathering of Associates at his studio to pursue "a clearer idea of their general views concerning their relations to the Academy." (Prior to a constitutional revision of 1906, Associates had no role in the management of Academy affairs, all powers being vested in the Academicians.) The outcome of the meeting, attended by about twenty long-standing Associates, was a fairly inflammatory "memorial," drafted by a committee of three (including Colyer), recommending abolition of the membership "caste system." A second meeting, held about a week later, was substantially concerned with second thoughts; the memorial was withdrawn, but the full proceedings of both meetings were published in a pamphlet, doubtless causing the Academicians some discomfort.

During the later part of his life Colyer worked increasingly as a landscape painter. The Academy exhibited his views of the West as well as of rural Connecticut. The eulogy prepared by the Academy when he died paid tribute not only to his career as a portrait and landscape painter but also to his interest in public affairs and concern for social reform.

Colyer was initially elected an Associate in 1849 but did not qualify. That is, he did not submit a diploma portrait within a year of being elected. In May 1850, when his year had already expired, he notified the Council specifically declining the election, apparently because the hanging committee for that year's annual exhibition had failed to find room for drawings of his that the jury had accepted. His resentment over this incident seems not to have abated by the time he was again elected an Associate, at the annual meeting of 1851; this point was somehow made to the Council, for in April 1852 it entered a resolution of apology to "Mr. Colyer and his Friends" into the minutes. Once this resolution was communicated to the artist, he replied graciously, accepting his election and offering as his diploma presentation the portrait of him by Thomas Hicks then on view in the annual exhibition. A month later, at its annual meeting, the Academy made a further gesture of conciliation-and perhaps laid

groundwork for teaching Colyer a lesson in tolerance-by naming him to the hanging committee for the annual exhibition of 1853.

Throughout his life Colyer was a committed citizen. During the Civil War he nursed the ill and wounded, representing the New York YMCA, of which he was later president. His service generally stemmed from the philanthropic impulse to assist the unfortunate; thus it is not surprising that he was instrumental in the founding of the Artists' Fund Society in 1859 and was its first secretary. He also proved an effective politician. His dedication to public service and apparent facility with the ways of legislatures probably prompted the Council to send him in the spring of 1866 to Albany to lobby on behalf of a bill to secure tax-exempt status for the Academy; the measure passed.

In 1866 Colyer established residence near Darien, Connecticut, though he maintained a New York studio for approximately the next ten years. In the late 1860s he was elected to the Connecticut legislature. In the post-Civil War years, too, he served on the U.S. Indian Commission. This work took him frequently to the West, notably to Alaska, where he carefully recorded the landscape in his work.

These demands on Colyer's time and attention surely explain why he did not submit paintings to Academy annuals in the late 1860s and early 1870s. It is also likely that his residence outside New York, frequent extended travels, and compelling extra-artistic preoccupations collectively account for the fact that he did not advance to Academician. However, there may have been another contributing factor. In response to a general appeal the Council made to members in 1874 to give the Academy greater support-especially in helping ensure the quality of submissions to the exhibitions-Colyer organized a gathering of Associates at his studio to pursue "a clearer idea of their general views concerning their relations to the Academy." (Prior to a constitutional revision of 1906, Associates had no role in the management of Academy affairs, all powers being vested in the Academicians.) The outcome of the meeting, attended by about twenty long-standing Associates, was a fairly inflammatory "memorial," drafted by a committee of three (including Colyer), recommending abolition of the membership "caste system." A second meeting, held about a week later, was substantially concerned with second thoughts; the memorial was withdrawn, but the full proceedings of both meetings were published in a pamphlet, doubtless causing the Academicians some discomfort.

During the later part of his life Colyer worked increasingly as a landscape painter. The Academy exhibited his views of the West as well as of rural Connecticut. The eulogy prepared by the Academy when he died paid tribute not only to his career as a portrait and landscape painter but also to his interest in public affairs and concern for social reform.