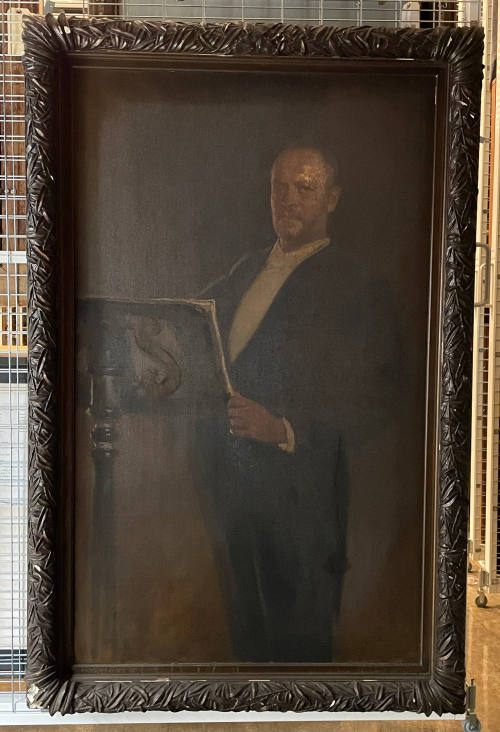

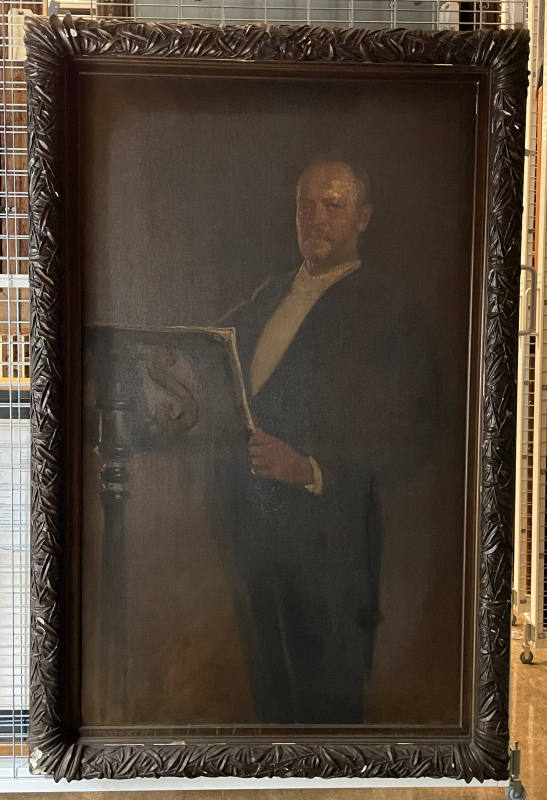

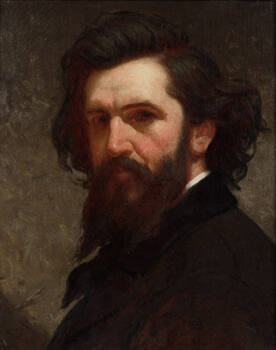

American, 1856 - 1915

At the time of his death, Alexander was one of the most celebrated and respected names in the American art world. He began his life less auspiciously, an an impoverished orphan raised in the strict Presbyterian household of his maternal grandparents. By age twelve, he had quit school to work as a messenger at the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company, Pittsburgh, but he was pursuaded by the firm's president, Edward J. Allen--who became Alexander's guardian--to return and finish high school.

Determined to embark on an artistic career, Alexander came to New York and took a job as an office boy at Harper Brothers. Eight months later, he was promoted to the illustration department, his first signed drawing appearing in late 1875. When he left for Europe two years later, Alexander continued to supply Harper's with illustrations.

After a brief and disappointing stay in Paris (the Ecole des Beaux-Arts was closed), he went to Munich where he studied for several months at the Academy of Fine Arts. Soon, however, he joined fellow Americans Frank Duveneck, Walter Shirlaw, and Joseph de Camp at the artists' colony in the Holy Cross Monastery at Polling, Bavaria. There he began painting in the dark, thickly impastoed style favored by Duveneck. He traveled with Duveneck to Italy in 1879, dividing his time between Venice, where he became acquainted with Whistler, and Florence, where he taught some small classes.

Returning to New York in 1881, Alexander established a studio in the German Bank Building, supporting himself through portrait commissions from Harper's and the Century Magazine, and his salary as a drawing instructor at Princeton University. He traveled often: to the American West in 1883, to Europe and North Africa in 1884, to England in 1886. In 1887, he married Elizabeth Alexander (no relation), a writer and socialite who would later make their Parisian residence into an artistic and intellectual salon.

Several years after the marriage, the frail Alexander suffered a violent flu attack and a nervous breakdown. The couple and their young son left for France in 1891 so that the artist might recuperate. Their "temporary" visit lasted a decade. His first paintings after a several years withdrawal from work, where shown at the Salon of 1893. These works, three portraits, were an immediate success, and he soon achieved a degree of fame which far outshone his moderately successful New York career.

In the experimental atmosphere of Paris, Alexander's art underwent a change. His palette lightened and thinned; his figures, formed in long, sweeping lines, projected a new decorative, rather two-dimensional character. Although never a part of the symbolist movement, he knew many symbolist artists and poets and was sympathetic to their use of color and mood to create meaning. The emphatic curves of the art nouveau style were also influential. Rapidly achieving prominence in European cultured circles, Alexander was elected to both the Vienna and Munich Secessions in 1897. Patrons in the United States also took note. In 1895 he received a commission of a series of murals, The Evolution of the Book, for the Library of Congress.

Upon returning permanently to New York in 1901, Alexander was immediately elected an associate and then full member of the National Academy. He became quite active in Academy affairs, serving on the Council from 1903 to 1906 and 1908/09, and as president of the Academy from 1909 to 1915. Although he was always busy with portraits, figures subjects, and mural projects (the most important of which were left unfinished at his death), Alexander also found time to experiment in theatre design, and to take an active role in many civic and professional organizations. Three of these in addition to the NAD--the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the School Art League, and the MacDowell Club--elected him to their presidencies. During the last years of his life, Alexander was the impassioned and highly visible spokesperson for the movement to construct a municipal arts building and a permanent home for the National Academy.

JD

Determined to embark on an artistic career, Alexander came to New York and took a job as an office boy at Harper Brothers. Eight months later, he was promoted to the illustration department, his first signed drawing appearing in late 1875. When he left for Europe two years later, Alexander continued to supply Harper's with illustrations.

After a brief and disappointing stay in Paris (the Ecole des Beaux-Arts was closed), he went to Munich where he studied for several months at the Academy of Fine Arts. Soon, however, he joined fellow Americans Frank Duveneck, Walter Shirlaw, and Joseph de Camp at the artists' colony in the Holy Cross Monastery at Polling, Bavaria. There he began painting in the dark, thickly impastoed style favored by Duveneck. He traveled with Duveneck to Italy in 1879, dividing his time between Venice, where he became acquainted with Whistler, and Florence, where he taught some small classes.

Returning to New York in 1881, Alexander established a studio in the German Bank Building, supporting himself through portrait commissions from Harper's and the Century Magazine, and his salary as a drawing instructor at Princeton University. He traveled often: to the American West in 1883, to Europe and North Africa in 1884, to England in 1886. In 1887, he married Elizabeth Alexander (no relation), a writer and socialite who would later make their Parisian residence into an artistic and intellectual salon.

Several years after the marriage, the frail Alexander suffered a violent flu attack and a nervous breakdown. The couple and their young son left for France in 1891 so that the artist might recuperate. Their "temporary" visit lasted a decade. His first paintings after a several years withdrawal from work, where shown at the Salon of 1893. These works, three portraits, were an immediate success, and he soon achieved a degree of fame which far outshone his moderately successful New York career.

In the experimental atmosphere of Paris, Alexander's art underwent a change. His palette lightened and thinned; his figures, formed in long, sweeping lines, projected a new decorative, rather two-dimensional character. Although never a part of the symbolist movement, he knew many symbolist artists and poets and was sympathetic to their use of color and mood to create meaning. The emphatic curves of the art nouveau style were also influential. Rapidly achieving prominence in European cultured circles, Alexander was elected to both the Vienna and Munich Secessions in 1897. Patrons in the United States also took note. In 1895 he received a commission of a series of murals, The Evolution of the Book, for the Library of Congress.

Upon returning permanently to New York in 1901, Alexander was immediately elected an associate and then full member of the National Academy. He became quite active in Academy affairs, serving on the Council from 1903 to 1906 and 1908/09, and as president of the Academy from 1909 to 1915. Although he was always busy with portraits, figures subjects, and mural projects (the most important of which were left unfinished at his death), Alexander also found time to experiment in theatre design, and to take an active role in many civic and professional organizations. Three of these in addition to the NAD--the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the School Art League, and the MacDowell Club--elected him to their presidencies. During the last years of his life, Alexander was the impassioned and highly visible spokesperson for the movement to construct a municipal arts building and a permanent home for the National Academy.

JD