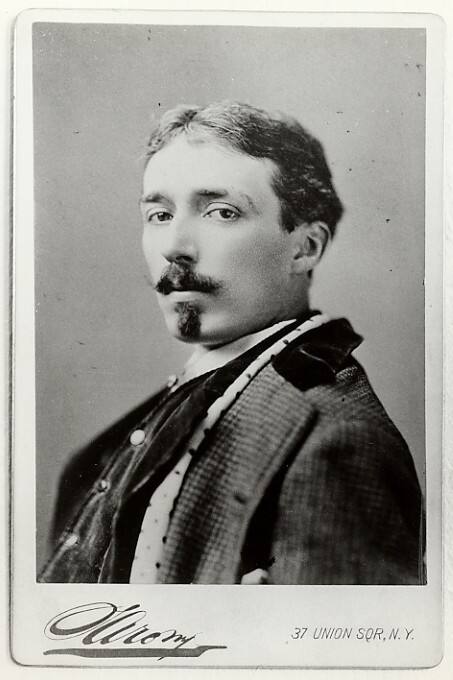

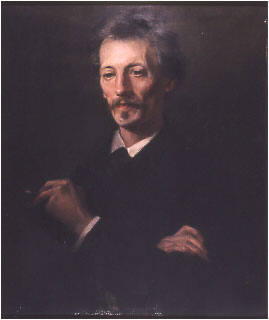

American, 1852 - 1917

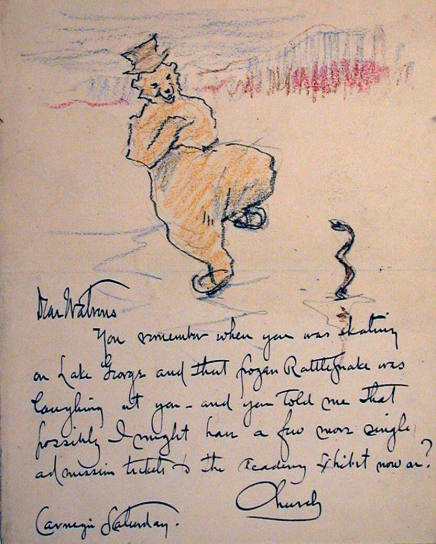

Beckwith's artistic education began in Chicago, where his family had moved while he was still a baby. At his father's insistence, he briefly attended several New York and Ohio military academies, however the nine-year-old boy was miserable and had to be withdrawn more than once for severe inflammatory rheumatism. Beckwith's constitution was delicate, and ill health plagued him the throughout his life. Back in Chicago, he began drawing by age twelve. Some years later, he was enrolled at the Chicago Academy of Design where he and his friend Frederick Stuart Church drew from the antique under Conrad Diehl.

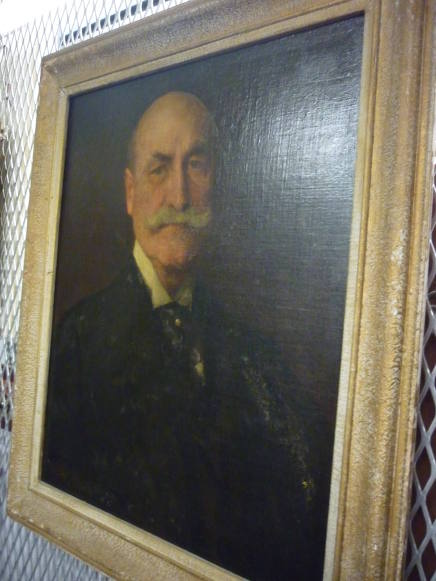

The 1871 Chicago fire left his merchant father without a home or business. This family setback was the impetus for Beckwith to move to New York where he enrolled in the antique class of the National Academy School for the 1871-72 season, the first full year the school was under direction of Lemuel Wilmarth. His poor health, however, made his attendance irregular. Wilmarth's encouragements helped him through this difficult time, and the following year he was admitted to the life class. During this period, he received support from his wealthy uncle, art patron John H. Sherwood.

On October 3, 1873, Beckwith sailed for England. It was a difficult decision, as he was plagued by self-doubt and financial woes. Once in Europe, however, he stayed for five years. Upon arriving, he reacted badly to the English climate, and despite an admiration for the pictures of Landseer, he quickly went on to Paris and entered the studio of Emile Auguste Carolus-Duran. "Then," he later wrote in "Souveniers and Reminiscences," "I think my real Art life began."

Carolus-Duran, then only thirty-five, was known for his flashy portraits and vigorous paint application. In time, Beckwith became a favorite of the master, working as his chief assistant both privately and in the school. In 1875, he and fellow students John Singer Sargent and Frank Fowler helped Carolus-Duran with his large ceiling decoration, The Apotheosis of Marie de Medici, in the Luxembourg Palace. It is perhaps surprising that Beckwith became so devoted to a teacher whose technique differed considerably from his own careful work. He recognized the shortcomings of Carolus-Duran's method, however, and to prepare to compete for the concours to enter the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he sought additional training in drawing at the Acad‚mie Suisse. He also worked in Joseph-Florentin-L‚on Bonnat's studio at night. After one unsuccessful attempt, he was admitted to the Ecole in February 1875. Nonetheless, he continued to work primarily with Carolus-Duran.

The American students of Carolus-Duran were sometimes considered renegades by the other Parisian studios, and they

often banded together while traveling during the summer. Beckwith spent the warm months variously in Fontainebleau, Italy,

and Germany. It was in Munich in 1875 that he met William Merritt Chase. At the time, he thought Chase the greatest American student in Europe.

When he and Chase returned to New York in 1878, they were immediately hired as instructors at the Art Students League. It was hoped that Beckwith's demanding drawing course would invigorate the League's curriculum. Chase's freer painting class was seen as a foil to the rigor of Beckwith's method. "Becky" became a familiar fixture at the League, teaching there for almost twenty years. Known throughout New York as an important pedagogue, he gave additional classes at the Brooklyn Art Guild and the Cooper-Union school.

Beckwith's main concern, however, was his own work. After his return from France, he began painting portraits and ideal female figures. He moved into his uncle's Sherwood Studio Building at Fifty-seventh Street and Sixth Avenue soon after it was completed in 1880. There he produced most of his work until his move to Italy in 1910.

He began showing regularly at the Academy in 1877 and continued to exhibit in the annuals until his death. Other organizations in which he was active include the Society of American Artists which he served as treasurer from 1881 to 1887 and remained a member of its governing board to 1892; the Society of Painters in Pastel; and the American Water Color Society. In 1884, with Chase, he organized the exhibition to raise funds to construct the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty pedestal. He served on the Council from 1895 to 1901, holding the position of corresponding secretary from 1896 to 1898. In this same period he chaired the Academy's "Ways and Means Committee" in its vain effort to raise fund to erect a new building.

In spite of his activities and the recognition he received by such commissions as the murals for the dome of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Beckwith remained insecure about his abilities. His diaries attest to continued anxieties well into middle age.

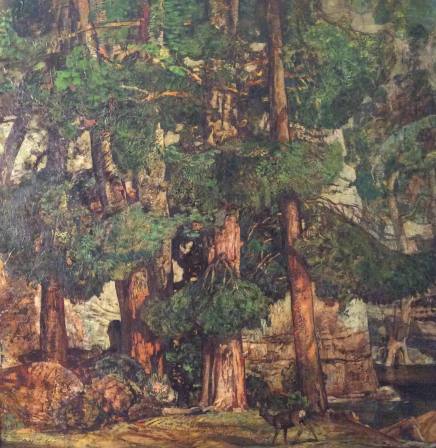

In 1910, after a somewhat disappointing public sale of his studio contents, he and his wife Bertha left for Italy. There the artist concentrated on small landscape sketches. By 1912, he was again at work in New York, often exhibiting small drawings and pastels. His work, however, was increasingly out of step with the times. He reacted strongly against the change of taste away from academic painting and was a vocal crusader against the "new art."

In 1917, while visiting with the eighty-year-old Thomas Moran in California, he began writing his autobiography, "Souvenirs and Reminiscences," and continued work on it at his summer home in Onteora, New York, but he died soon after, leaving the manuscript incomplete.

In the minds of his fellow artists, the name of J. Carroll Beckwith always stood for an unwavering commitment to the highest ideals of academic art. Throughout his career, Beckwith remained true to his French training, first as a young portrait painter fresh from years of Parisian study, then as an influential teacher of careful, accurate drawing, and finally as an uncompromising conservative bemoaning the state of early twentieth-century art.

At the death of Bertha H. Beckwith in 1925, the manuscript "Souveniers and Reminiscences," forty-one of his yearly diaries covering the period 1871 through 1917, photographs, and other memorabilia passed to the Academy by her bequest.

The 1871 Chicago fire left his merchant father without a home or business. This family setback was the impetus for Beckwith to move to New York where he enrolled in the antique class of the National Academy School for the 1871-72 season, the first full year the school was under direction of Lemuel Wilmarth. His poor health, however, made his attendance irregular. Wilmarth's encouragements helped him through this difficult time, and the following year he was admitted to the life class. During this period, he received support from his wealthy uncle, art patron John H. Sherwood.

On October 3, 1873, Beckwith sailed for England. It was a difficult decision, as he was plagued by self-doubt and financial woes. Once in Europe, however, he stayed for five years. Upon arriving, he reacted badly to the English climate, and despite an admiration for the pictures of Landseer, he quickly went on to Paris and entered the studio of Emile Auguste Carolus-Duran. "Then," he later wrote in "Souveniers and Reminiscences," "I think my real Art life began."

Carolus-Duran, then only thirty-five, was known for his flashy portraits and vigorous paint application. In time, Beckwith became a favorite of the master, working as his chief assistant both privately and in the school. In 1875, he and fellow students John Singer Sargent and Frank Fowler helped Carolus-Duran with his large ceiling decoration, The Apotheosis of Marie de Medici, in the Luxembourg Palace. It is perhaps surprising that Beckwith became so devoted to a teacher whose technique differed considerably from his own careful work. He recognized the shortcomings of Carolus-Duran's method, however, and to prepare to compete for the concours to enter the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he sought additional training in drawing at the Acad‚mie Suisse. He also worked in Joseph-Florentin-L‚on Bonnat's studio at night. After one unsuccessful attempt, he was admitted to the Ecole in February 1875. Nonetheless, he continued to work primarily with Carolus-Duran.

The American students of Carolus-Duran were sometimes considered renegades by the other Parisian studios, and they

often banded together while traveling during the summer. Beckwith spent the warm months variously in Fontainebleau, Italy,

and Germany. It was in Munich in 1875 that he met William Merritt Chase. At the time, he thought Chase the greatest American student in Europe.

When he and Chase returned to New York in 1878, they were immediately hired as instructors at the Art Students League. It was hoped that Beckwith's demanding drawing course would invigorate the League's curriculum. Chase's freer painting class was seen as a foil to the rigor of Beckwith's method. "Becky" became a familiar fixture at the League, teaching there for almost twenty years. Known throughout New York as an important pedagogue, he gave additional classes at the Brooklyn Art Guild and the Cooper-Union school.

Beckwith's main concern, however, was his own work. After his return from France, he began painting portraits and ideal female figures. He moved into his uncle's Sherwood Studio Building at Fifty-seventh Street and Sixth Avenue soon after it was completed in 1880. There he produced most of his work until his move to Italy in 1910.

He began showing regularly at the Academy in 1877 and continued to exhibit in the annuals until his death. Other organizations in which he was active include the Society of American Artists which he served as treasurer from 1881 to 1887 and remained a member of its governing board to 1892; the Society of Painters in Pastel; and the American Water Color Society. In 1884, with Chase, he organized the exhibition to raise funds to construct the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty pedestal. He served on the Council from 1895 to 1901, holding the position of corresponding secretary from 1896 to 1898. In this same period he chaired the Academy's "Ways and Means Committee" in its vain effort to raise fund to erect a new building.

In spite of his activities and the recognition he received by such commissions as the murals for the dome of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Beckwith remained insecure about his abilities. His diaries attest to continued anxieties well into middle age.

In 1910, after a somewhat disappointing public sale of his studio contents, he and his wife Bertha left for Italy. There the artist concentrated on small landscape sketches. By 1912, he was again at work in New York, often exhibiting small drawings and pastels. His work, however, was increasingly out of step with the times. He reacted strongly against the change of taste away from academic painting and was a vocal crusader against the "new art."

In 1917, while visiting with the eighty-year-old Thomas Moran in California, he began writing his autobiography, "Souvenirs and Reminiscences," and continued work on it at his summer home in Onteora, New York, but he died soon after, leaving the manuscript incomplete.

In the minds of his fellow artists, the name of J. Carroll Beckwith always stood for an unwavering commitment to the highest ideals of academic art. Throughout his career, Beckwith remained true to his French training, first as a young portrait painter fresh from years of Parisian study, then as an influential teacher of careful, accurate drawing, and finally as an uncompromising conservative bemoaning the state of early twentieth-century art.

At the death of Bertha H. Beckwith in 1925, the manuscript "Souveniers and Reminiscences," forty-one of his yearly diaries covering the period 1871 through 1917, photographs, and other memorabilia passed to the Academy by her bequest.