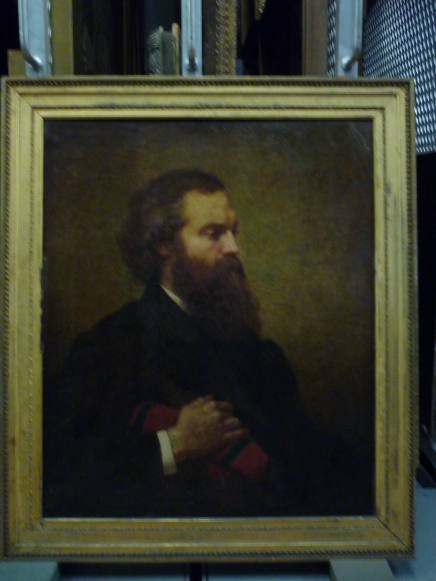

American, 1856 - 1919

Born into a family of intellectuals, Kenyon Cox spent much of his early career convincing his parents that painting was an advantageous and profitable profession. Between ages nine and thirteen, he spent most of his time in bed, the result of a serious tumorous growth on his chin. It was at this time that he took up drawing. In 1869, after a series of successful operations, he continued his studies. Cox spent four years at the McMicken School of Design, Cincinnati, and supplemented his studies with night work at the University of Cincinnati. In 1874 Frank Duveneck returned to Cincinnati to open a life class at the [Unanswered query: correct name, no punctuation?:] Ohio Mechanics Institute, which Cox attended. His fellow students included Robert Blum and John H. Twachtman.

Along with Blum, Cox spent part of 1876 studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, under Christian Schussele. Blum and Cox disliked their teacher and dreamed of traveling to Europe to study the work of their idols, Giovanni Boldini and Mariano Fortuny. Japan was also of great interest to the two students, particularly after they visited that country's exhibits at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

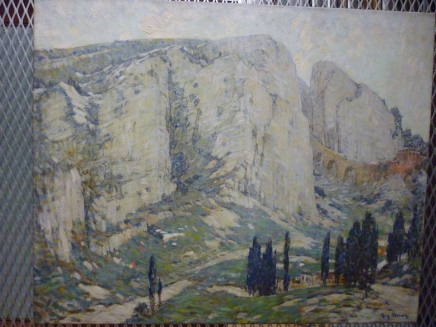

Cox left for France in 1877, visiting Rouen before arriving in Paris. That winter, he entered the atelier of Emile Carolus-Duran, and he made his first visit to the town of Grez-sur-Loing, near Fontainebleau, which would become his favorite vacation spot. Cox must have impressed his teacher, for by 1878 he was assisting him with his painting Apotheosis of Marie de Medici (Luxembourg Palace). However, Cox grew disenchanted with Carolus-Duran's lax methods, especially after he failed to be admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in March 1878. To add academic rigor to his training, he took a class taught by Alexandre Cabanel. After a summer in Rouen, Grez, and Italy, he also began attending the Académie Julian, where he excelled. In March 1879 he finally was admitted to the Ecole, to work under Jean-Léon Gérôme, with whom he remained until 1882. During these years he also was painting portraits and spending time in Grez, London, and Brussels, where he worked briefly on a large panorama before quitting because of his employers' refusal to provide costumed models.

Returning first to Cincinnati in 1882 and then to New York in 1883, Cox was almost immediately elected to the Society of American Artists, an organization in which he played a prominent role for over two decades. Permanently marked by his academic training abroad, he began exhibiting "academies," or large-scale nude studies, which stirred considerable controversy in the American art world. His work was not well received, and for fifteen years he struggled to live on his portrait and landscape work. Cox had begun writing criticism while abroad; now, to supplement his income, he turned seriously to literary work, launching a long career as a critic, author, and lecturer. His initial job was with the Nation, but he was soon writing for other periodicals as well. He also did illustration work for Century and other magazines. In 1886, after Thomas Wilmer Dewing and Will Low had declined the job offer and recommended Cox, Dodd, Mead and Company engaged him to illustrate Dante Gabriel Rossetti's book of poetry Blessed Damozel for fifteen hundred dollars. Another source of income for him was teaching at the Art Students League; there he met the student Louise Howland King, who became his wife in 1892.

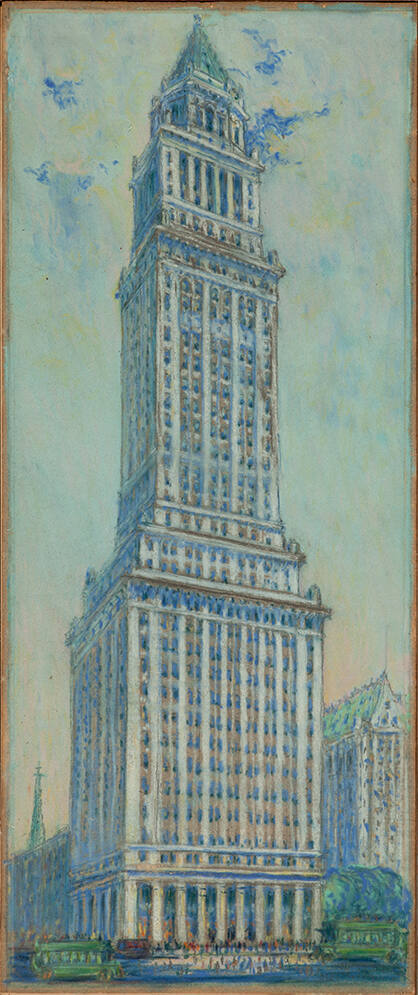

In the 1890s Cox's career was on the upswing, thanks to his experimentation in decorative murals. Over the years he executed important works in the Iowa and Minnesota state capitols; the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.; the Appellate Court Building, New York; the Essex County Courthouse, Newark, New Jersey; the Citizens Bank, Cleveland, Ohio; and the Walker Art Building at Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine. He was active in the Society of Mural Painters, serving as its first vice-president.

The Academy first honored Cox in 1889 with a Julius Hallgarten Prize. But perhaps because of his conflicting work as a critic, coupled with his conspicuous attachment to the Society of American Artists, eleven years passed before he was elected an Associate. Advancement to Academician came more promptly, and at the earliest constitutionally permitted opportunity thereafter he was elected to the Council, beginning a thirteen-year period of active involvement in the management of Academy affairs. Cox served on the Council from 1904 to 1907. He was then elected recording secretary, a post he held until 1910, when he returned to the Council for a three-year term. Following the obligatory year off Council, he was elected to another three-year term in 1914 and again reelected in 1918, but this time served only one year. He was a frequent lecturer in the Academy school from 1900 to 1917 and was on the school faculty, teaching composition, for the seasons of 1913-14 through 1917-18. The second and final award given Cox for work in Academy exhibitions was an Isidor Gold Medal, presented in the winter exhibition of 1910.

Still plagued with money problems late in life, he continued writing and lecturing. In 1905 he began publishing a series of volumes of his essays, the most enduring of which was The Classic Point of View (1911). Ironically, although Cox's own career had been hindered by his progressive views of the 1880s, he became ultraconservative toward the end of his life, vehemently attacking exhibitions such as the 1913 Armory Show.

In 1959 Cox's children presented the Academy with a number of his drawings, sketchbooks, and oil sketches, most of which the Academy distributed to museums throughout the country.

Along with Blum, Cox spent part of 1876 studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, under Christian Schussele. Blum and Cox disliked their teacher and dreamed of traveling to Europe to study the work of their idols, Giovanni Boldini and Mariano Fortuny. Japan was also of great interest to the two students, particularly after they visited that country's exhibits at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

Cox left for France in 1877, visiting Rouen before arriving in Paris. That winter, he entered the atelier of Emile Carolus-Duran, and he made his first visit to the town of Grez-sur-Loing, near Fontainebleau, which would become his favorite vacation spot. Cox must have impressed his teacher, for by 1878 he was assisting him with his painting Apotheosis of Marie de Medici (Luxembourg Palace). However, Cox grew disenchanted with Carolus-Duran's lax methods, especially after he failed to be admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in March 1878. To add academic rigor to his training, he took a class taught by Alexandre Cabanel. After a summer in Rouen, Grez, and Italy, he also began attending the Académie Julian, where he excelled. In March 1879 he finally was admitted to the Ecole, to work under Jean-Léon Gérôme, with whom he remained until 1882. During these years he also was painting portraits and spending time in Grez, London, and Brussels, where he worked briefly on a large panorama before quitting because of his employers' refusal to provide costumed models.

Returning first to Cincinnati in 1882 and then to New York in 1883, Cox was almost immediately elected to the Society of American Artists, an organization in which he played a prominent role for over two decades. Permanently marked by his academic training abroad, he began exhibiting "academies," or large-scale nude studies, which stirred considerable controversy in the American art world. His work was not well received, and for fifteen years he struggled to live on his portrait and landscape work. Cox had begun writing criticism while abroad; now, to supplement his income, he turned seriously to literary work, launching a long career as a critic, author, and lecturer. His initial job was with the Nation, but he was soon writing for other periodicals as well. He also did illustration work for Century and other magazines. In 1886, after Thomas Wilmer Dewing and Will Low had declined the job offer and recommended Cox, Dodd, Mead and Company engaged him to illustrate Dante Gabriel Rossetti's book of poetry Blessed Damozel for fifteen hundred dollars. Another source of income for him was teaching at the Art Students League; there he met the student Louise Howland King, who became his wife in 1892.

In the 1890s Cox's career was on the upswing, thanks to his experimentation in decorative murals. Over the years he executed important works in the Iowa and Minnesota state capitols; the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.; the Appellate Court Building, New York; the Essex County Courthouse, Newark, New Jersey; the Citizens Bank, Cleveland, Ohio; and the Walker Art Building at Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine. He was active in the Society of Mural Painters, serving as its first vice-president.

The Academy first honored Cox in 1889 with a Julius Hallgarten Prize. But perhaps because of his conflicting work as a critic, coupled with his conspicuous attachment to the Society of American Artists, eleven years passed before he was elected an Associate. Advancement to Academician came more promptly, and at the earliest constitutionally permitted opportunity thereafter he was elected to the Council, beginning a thirteen-year period of active involvement in the management of Academy affairs. Cox served on the Council from 1904 to 1907. He was then elected recording secretary, a post he held until 1910, when he returned to the Council for a three-year term. Following the obligatory year off Council, he was elected to another three-year term in 1914 and again reelected in 1918, but this time served only one year. He was a frequent lecturer in the Academy school from 1900 to 1917 and was on the school faculty, teaching composition, for the seasons of 1913-14 through 1917-18. The second and final award given Cox for work in Academy exhibitions was an Isidor Gold Medal, presented in the winter exhibition of 1910.

Still plagued with money problems late in life, he continued writing and lecturing. In 1905 he began publishing a series of volumes of his essays, the most enduring of which was The Classic Point of View (1911). Ironically, although Cox's own career had been hindered by his progressive views of the 1880s, he became ultraconservative toward the end of his life, vehemently attacking exhibitions such as the 1913 Armory Show.

In 1959 Cox's children presented the Academy with a number of his drawings, sketchbooks, and oil sketches, most of which the Academy distributed to museums throughout the country.