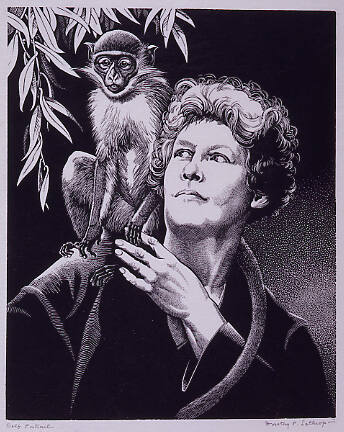

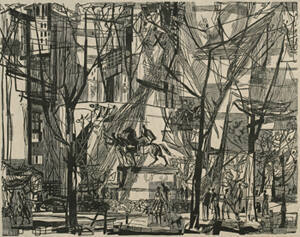

TitleSelf-Portrait

Artist

Dorothy Pulis Lathrop

(1891-1980)

Date1952

MediumWood engraving on thin cream laid paper

DimensionsSheet size: 13 × 9 7/16 in.

Image size: 9 15/16 × 8 in.

Mat size: 19 3/8 × 15 1/2 in.

SignedSigned in graphite at LR: "Dorothy P. Lathrop-"

SubmissionANA diploma presentation, April 7, 1952

Credit LineNational Academy of Design, New York, NY

Object number1982.1002

Label TextDPL's grandfather owned a bookstore. Her mother Ida Pulis Lathrop, (1859-1937) was a painter and her sister Gertrude Lathrop was a sculptor and member of the National Academy. Her work has been exhibited with theirs. She studied with Arthur Wesley Dow and Teachers College, Columbia, with Henry McCarter at the Pennsylvania Academy and F. Luis Mora at the Art Students League.DPL became an award-winning illustrator of children's books. In 1938, she was honored as the very first recipient of the Caldecott Medal for her work on "The Animal of the Bible," (1937) by Helen Dean Fish. The Caldecott Medal was named in honor of nineteenth-century English illustrator Randolph Caldecott. It is awarded annually by the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association, to the artist with the most distinguished American picture book for children. Arguably her most famous works were the illustrations for Rachel Field's, "Hitty, Her First Hundred Years," the story of a doll. The book was awarded the Newbery Medal in 1930; a new edition was published in December 1999.

Dorothy Pulis Lathrop was best known for her depictions of animals, her favorite subject. She liked to have animals before her when she drew, but relied upon photographs to represent those that she could not find in zoos. She had an intense desire to present the particular personalities and ways of animals, which she shared with her sister, Gertrude Lathrop. whose bronze sculpture Silver Marten Rabbit is in this exhibition.

In her Caldecott acceptance speech DPL said, "I can't help wishing that just now all of you were animals. Of course, technically you are, but if only I could look down into a sea of furry faces, I would know better what to say." This statement belies her eloquence. Later in the speech she says:

"What we love, we gloat over and feast our eyes upon. And when we look again and again at any living creature, we cannot help but perceive its subtlety of line, its exquisite patterning and all its unbelievable intricacy and beauty. The artist who draws what he does not love, draws from a superficial concept. But the one who loves what he draws is very humble trying to translate into an alien medium life itself, and it is his joy and his pain that he knows that life to be matchless."

She goes on to say how no one more than the artist is "convinced of the unity of all life..., who sits before its different phases so long and silently, seeing them in a great intimacy." She believed that the artist observing another creature "becomes that creature. Or, as the eastern philosophers put it, he "sees all creatures in himself, himself in all creatures."