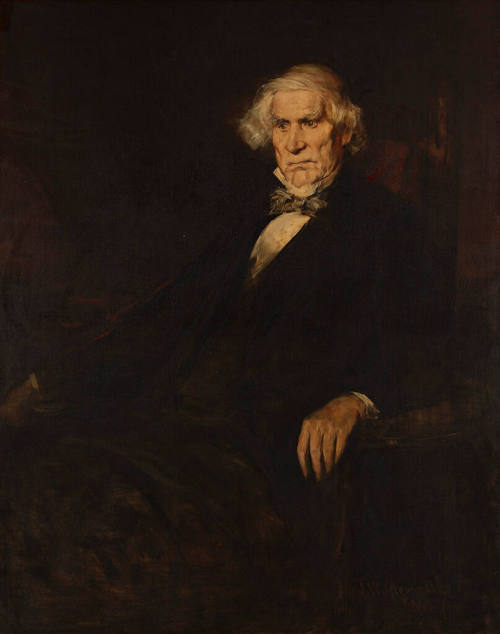

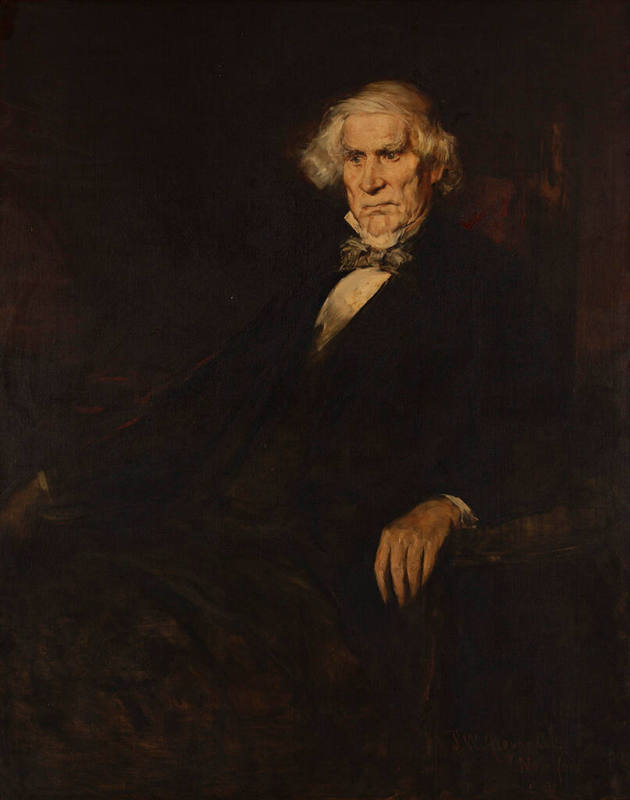

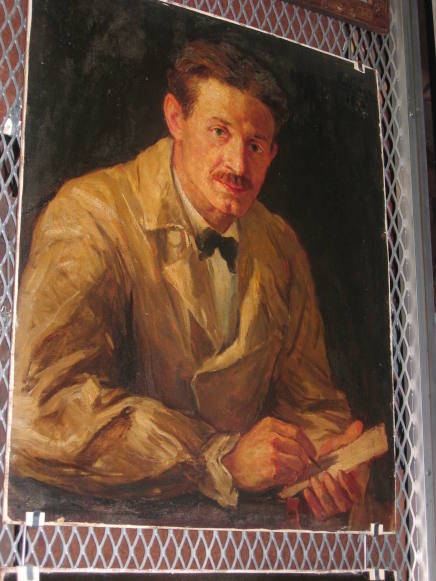

TitleThurlow Weed

Artist

John White Alexander

(American, 1856 - 1915)

Date1881-1882

MediumOil on canvas

DimensionsUnframed: 50 × 40 in.

Framed: 53 3/8 × 43 3/8 × 2 3/8 in.

SignedSigned lower right: "J. W. Alexander / New York"

Credit LineNational Academy of Design, New York, NY, Gift of Mrs. John White Alexander

Object number23-P

Label TextIn 1881, Alexander received a commission from Harper's to execute a portrait drawing of Thurlow Weed (1797-1882). The artist was so taken by the older man's personality and appearance that he asked for sittings to paint an oil portrait. Thurlow Weed, a Rochester and Albany newspaper editor and publisher, had played an active part in national politics from the 1840s to the close of the Civil War. Initially as a member of the Whig party, and then as a Republican, he successfully advanced the careers of several presidential candidates. Known as a shrewd manipulator who would employ any method to achieve his aims, Weed lost political clout forever after supporting Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction policies in 1866. His stories must have entertained Alexander, for in 1881 he wrote to his friend, Ed Phelps, "Really I am very busy--painting several portraits--one of Thurlow Weed--who is certainly the most interesting sitter imaginable. I would not be surprised if he were to tell me he had been personally acquainted with Adam and Eve. Have the head finished and believe it about the best thing I have done."Alexander, newly returned from Europe, sought to establish his reputation by exhibiting the portrait in the 1882 Academy Annual. William Laurel Harris later called Thurlow Weed his "first success," and it is undeniable that the portrait received much press attention. It was not universally praised, however. Clarence Cook, writing in Art Amateur, called it "ghastly," and the reviewer of The Critic, although admitting that Alexander showed promise, criticized his "hardness of modeling and defective adjustment of flesh and cloth textures." In the spirit of his Munich teachers, Alexander had built up Weed's face with thick impasto.

Apparently, no attempt was made to sell the work until after Alexander's death. His widow conducted brief negotiations with the Weed family, but failed to reach an agreement. After an extended loan to the Brooklyn Museum, Mrs. Alexander gave the work to the Academy, emphasizing in a letter to President Hobart Nichols the painting's importance as "very typical of the earlier portraits painted by Mr. Alexander."

In 1881 Alexander received a commission from Harper's to execute a portrait drawing of Thurlow Weed (1797-1882). The artist was so taken by the older man's personality and appearance that he asked for sittings to paint an oil portrait. Weed, a Rochester and Albany newspaper editor and publisher, had played an active part in national politics from the 1840s to the close of the Civil War. Initially as a member of the Whig party and then as a Republican, he successfully advanced the careers of several presidential candidates, such as Henry Clay and William Henry Harrison. Known as a shrewd manipulator who would employ any method to achieve his aims, Weed lost political clout permanently after supporting Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction policies in 1866. His stories must have entertained Alexander, who in 1881 wrote to his friend Ed Phelps: "Really I am very busy-painting several portraits-one of Thurlow Weed-who is certainly the most interesting sitter imaginable. I would not be surprised if he were to tell me he had been personally acquainted with Adam and Eve. Have the head finished and believe it about the best thing I have done."

Newly returned from Europe, Alexander sought to establish his reputation by exhibiting the portrait in the 1882 Academy annual. William Laurel Harris later called Thurlow Weed the painter's "first success," and it is undeniable that the portrait received much press attention. It was not universally praised, however. Clarence Cook, writing in Art Amateur, called it "ghastly," and the reviewer for the Critic, although admitting that Alexander showed promise, criticized his "hardness of modeling and defective adjustment of flesh and cloth textures." In the spirit of his Munich teachers, Alexander has built up Weed's face with thick impasto. His harsh lighting emphasizes the brilliant flesh tones and the flurry of white hair, while leaving the rest of the canvas in darkness.

Apparently, no attempt was made to sell the work until after Alexander's death. His widow conducted brief negotiations with the Weed family but failed to reach an agreement. After an extended loan to the Brooklyn Museum, she gave the work to the Academy, emphasizing in a letter to President Hobart Nichols the painting's importance as "very typical of the earlier portraits painted by Mr. Alexander."