TitleA Magdalen

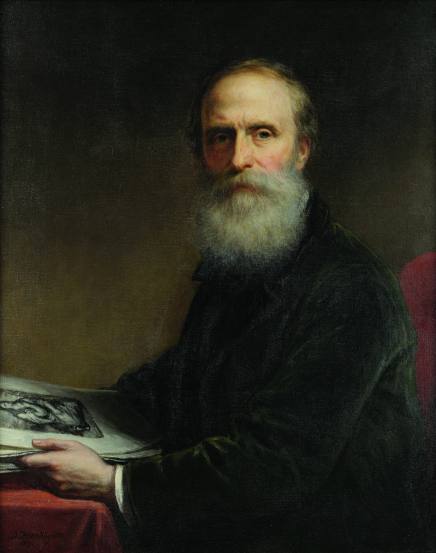

Artist

Daniel Huntington

(American, 1816 - 1906)

Date1852-1853

MediumOil on canvas

DimensionsUnframed: 50 × 39 3/4 in.

Framed: 61 5/8 × 51 1/2 × 5 1/2 in.

SignedSigned lower right: "D. Huntington/1853"; inside oval: "Huntington/London/1852?"

Credit LineNational Academy of Design, New York, Gift of the Overbrook Foundation, 1986

Object number1986.212

Label TextDaniel Huntington made several stays abroad in the 1850s. He visited London and Paris in 1852-53, and it was in London in the summer of 1853 that he completed A Magdalen. Seven figure and drapery studies for the painting survive (Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York). Huntington originally composed the image for the rectangular format of the canvas but painted out the corners and recomposed the foreground drapery to accommodate the elaborate oval-within-rectangle frame; he probably then added the second signature within the oval opening. According to an inscription on the back of the canvas, Huntington touched up the picture in about 1883, possibly to correct an earlier, unsuccessful attempt to repair severe surface cracking. He recorded in his "Inventory" that the cracking had been caused by an excessive use of megilp, a substance employed to impart a warm "Titianesque" glow to a canvas.According to Huntington's "Inventory," "A Magdalen" was acquired by Charles Augustus Lewis for $400, a price that included the frame. Lewis owned the painting by the time it was shown in the Academy annual of 1855. Lewis, who had graduated from Yale College, was a prosperous citizen of his hometown, New London, Connecticut. On his mother's side he was a first cousin of Harriet Sophia Richards, Huntington's wife, and was also distantly related to the artist himself. Lewis had commissioned a posthumous portrait of his son George in 1848, and Huntington painted two landscapes for him in 1856. His younger brother George Richards Lewis was one of Huntington's early patrons, buying his Italy (1843, unlocated) and other works. Huntington did a posthumous portrait of George Lewis for his widow in 1853, the year he died.

The precise significance of the Magdalen for Huntington is unclear. For an ambitious figure painter her characteristic flowing hair, emotional expression, and seminudity afforded an ideal vehicle. For the Victorian public, sympathetic to the theme of the fallen woman redeemed by religious faith, Mary Magdalen's symbolic penitence sanitized and sanctified her sensuality. Thus, despite her Catholic associations, she was a popular subject among Protestant Americans. "We are tired of Magdalens," complained the Knickerbocker critic who reviewed "A Magdalen" at the Academy. Proliferating Magdalens at that time included two by Huntington's former students Henry Peters Gray and Edward Harrison May. Both had been exhibited at the American Art-Union in 1848 and may have prompted Huntington to paint "Three Marys" of the next year.

Completed two years after his "Lecture on Christian Art," "A Magdalen" sums up Huntington's ideal of religious art. His hostility toward Catholicism was tempered by his admiration for its great artistic tradition. "Thousands will turn from the teaching of words," he wrote to Cornelius Ver Bryck in 1843, "but every eye is arrested by the picture." But, he went on to warn, "the higher and better the gift, the more base & perfidious is its abuse.-Miserable then is the wretch who impiously perverts the Divine art of painting to unholy uses." Even some of the great masters-Guido Reni, Veronese, Rubens, and Titian-he thought, sometimes painted too much for the senses, whereas "To form a completely satisfactory Christian picture the spiritual element should prevail, should be supreme." In engaging the tradition of the seminude penitent Magdalen, Huntington thus set himself the extra challenge of realizing a high-minded religious and moral message through the medium of sensual physicality.