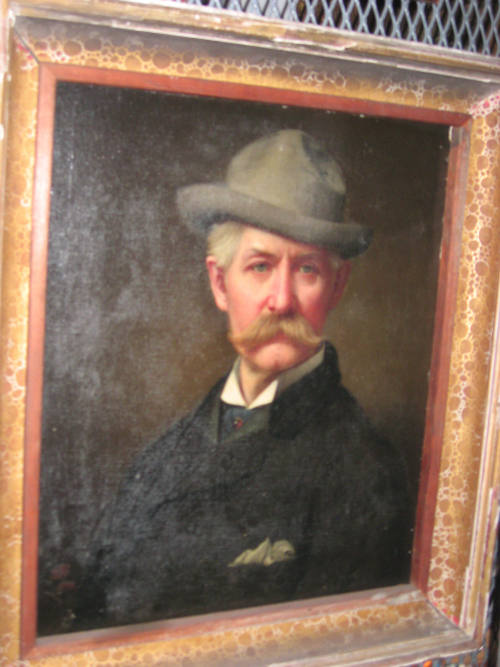

1827 - 1908

Like many aspects of his biography, the artistic education of David Johnson has not been precisely documented. Contrary to the hypothesis that he received no formal academic instruction, however, NAD records show that the teenage student was registered for two seasons (1845-7) at the Academy's Antique School where his classmates included future landscape colleagues Frederic Church, Sanford R. Gifford, and George Inness. Later he is known to have received advice from John F. Kensett, John W. Casilear, and Jasper Cropsey. He was studying the scenery of Upstate New York by 1849, the year of his first Academy exhibition, and three years later, he began appearing as an artist in the New York City directory.

Johnson's considered New York and New Hampshire views won him a respectable place within the Academy's hierarchy of landscape painters. He became involved in controversy briefly in 1874 when he served with John Beaufain Irving and Carl Ludwig Brandt on the Hanging Committee to select works for the Annual Exhibition. They rejected several paintings by John La Farge, who, insulted, pressed for the rights of Academicians to guaranteed acceptance. The conservative backlash to this discussion was one of a series of events which led to the founding of the Society of American Artists by disgruntled younger artists (NAD minutes, April 20 & 27, and May 13, 1874; Clark, 96-9; Fink, 73-9).

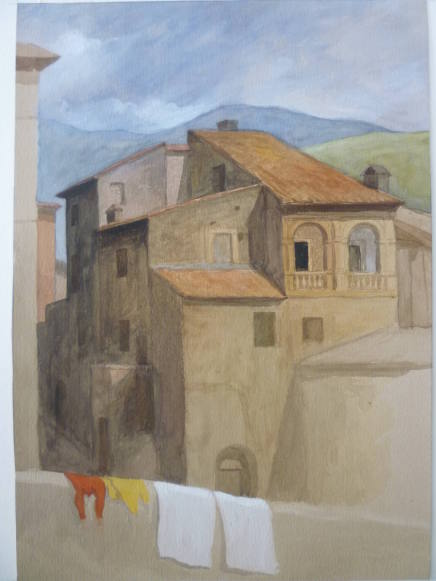

The paintings of Johnson were never immensely popular, and an 1890 sale of his work at the Fifth Avenue Galleries appears to indicate a certain financial duress. In 1894, following a thirteen-year period without a contribution to an NAD Annual, he gave up the YMCA studio he had occupied for over two decades. Ten years later, he retired to Walden, New York. Sixteen years after his death, the Academy received a letter from a Walden grocer who knew Johnson's widow explaining that she was penniless and unable to sell any of his pictures. The correspondent, J.S. Walker, mentioned works by Europeans for sale which Johnson had purchased abroad. The letter not only offers clues to Johnson's tastes (he owned works by Emile Charles Lambinet, Timol‚on Marie Lobrichon, Albert Arnz, F‚lix F.G.P. Ziem, and either Th‚odore or Philippe Rousseau, among others) but also appears both to settle the uncertain question of his having traveled to Europe and to explain what influences may have inspired his occasional departures from his normally meticulous naturalism for a broader Barbizon style.

Johnson's considered New York and New Hampshire views won him a respectable place within the Academy's hierarchy of landscape painters. He became involved in controversy briefly in 1874 when he served with John Beaufain Irving and Carl Ludwig Brandt on the Hanging Committee to select works for the Annual Exhibition. They rejected several paintings by John La Farge, who, insulted, pressed for the rights of Academicians to guaranteed acceptance. The conservative backlash to this discussion was one of a series of events which led to the founding of the Society of American Artists by disgruntled younger artists (NAD minutes, April 20 & 27, and May 13, 1874; Clark, 96-9; Fink, 73-9).

The paintings of Johnson were never immensely popular, and an 1890 sale of his work at the Fifth Avenue Galleries appears to indicate a certain financial duress. In 1894, following a thirteen-year period without a contribution to an NAD Annual, he gave up the YMCA studio he had occupied for over two decades. Ten years later, he retired to Walden, New York. Sixteen years after his death, the Academy received a letter from a Walden grocer who knew Johnson's widow explaining that she was penniless and unable to sell any of his pictures. The correspondent, J.S. Walker, mentioned works by Europeans for sale which Johnson had purchased abroad. The letter not only offers clues to Johnson's tastes (he owned works by Emile Charles Lambinet, Timol‚on Marie Lobrichon, Albert Arnz, F‚lix F.G.P. Ziem, and either Th‚odore or Philippe Rousseau, among others) but also appears both to settle the uncertain question of his having traveled to Europe and to explain what influences may have inspired his occasional departures from his normally meticulous naturalism for a broader Barbizon style.