Lorado Taft was raised in an academic environment and, in fact, lived in one for most of his life. His father was the principal of several schools in central Illinois as well as professor of natural sciences at the University of Illinois. In the art museum of the latter institution, the younger Taft helped to repair recently purchased but damaged antique cast collection. Thereby began his interest in sculpture.

After receiving a graduate degree from the University of Illinois in 1880, Taft studied for three years in Paris at the Ecole-des-Beaux-Arts under Augustin Dumont, J.M.B. Bonnaissieux, and Jules Thomas. He was at the top of his class and exhibited several times at the Salon. After a year spent at home in America, he returned to Paris for two more years of independent work. On his final return to the United States in 1886, he settled permanently in Chicago where he became an instructor in sculpture at the Art Institute, a position he held for twenty-two years. He revolutionized the teaching of sculpture there by insisting that students carve directly in the marble and not simply work in clay and plaster as was the tradition. Later, he lectured on art at the University of Chicago where he was made a professorial lecturer in 1909. He was named a non-resident professor at the Univeristy of Illinois in 1919.

Taft's most important early commission was for decorative sculpture for the Horticulture Building at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It brought him national recognition and he received a designer's medal for the project.

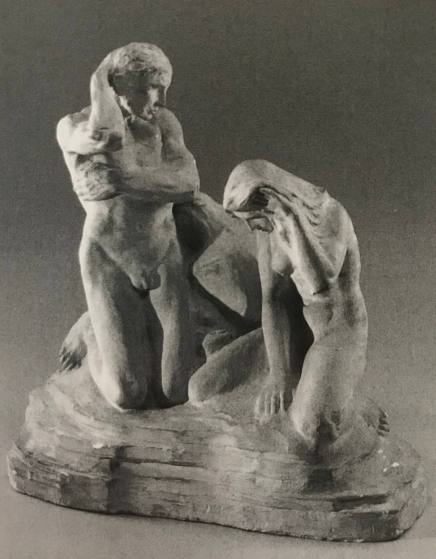

Taft's reputation rose gradually but steadily and by 1900 he had developed his own personal, and rather heroic style, characterized by a poetic and allegorical nature. This was realized, as Allen Weller has pointed out, through an increasing interest in depicting the complex interaction of figures. Among Taft's works from these years are Solitude of the Soul (1901, Chicago Art Institute) and The Blind (1908, University of Illinois), the latter of which was shown at the winter exhibition of the National Academy in 1908 (catalogue no. 373). These were supplemented by those staples of artistic survival, portrait busts and medallions. During the 1910s and '20s Taft produced many his mature work, particularly monumental sculptures such as Black Hawk (1911, Oregon, Illinois) and Lincoln, the Young Lawyer (1927, Urbana, Illinois). He also designed several complicated fountain projects such as The Great Lakes which was erected on the south side of the Chicago Art Institute in 1913. In 1906, Taft established a studio on the Midway in Chicago which became famous as the site of creation for these large and complicated conceptions.

Taft is best remembered today for his seminal History of American Sculpture, published in 1903 and still a standard, if somewhat dated, reference. A sequel, Modern Tendencies in Sculpture, in which he wrote of his contemporaries, came out in 1921. While his his sculptures are in many collections across the nation, perhaps Taft's most significant and impressive contribution was his energetic teaching of art history and his many attempts to bring art to the public, especially to young people. He styled himself an "art missionary" and spent most of his adult life living up to the claim. His most widel publicized lecture, known as "the clay talk," which he delivered many times, featured an on-stage demonstration of the modeling of the bust of a female subject who "changed from glamorous youth and beauty to haggard and shrunken old age" before the eyes of the mesmerized audience.

Among Taft's awards were the Palette and Chisel Club Prize at the Chicago Art Institute in 1899, a silver medal at the Buffalo exposition in 1901, a gold medal at the St. Louis exposition in 1904, the Art Institute's Montgomery Ward Prize in 1906, and a silver medal at the Panama-Pacific exposition in San Francisco in 1915. He was a member of the National Academy of Arts and Letters, the National Sculpture Society, and the American Institute of Architects.