Frank Duveneck is the painter most often cited as head of the Munich School of American painting. In 1861 he began working under Johann Schmitt in Covington, painting and carving church altarpieces and decorations. In 1868 he became an apprentice to the Munich-trained Wilhelm Lamprecht and traveled with him, assisting in his work painting murals in churches. It is believed that it was Lamprecht who encouraged Duveneck to go to Munich for training; he sailed for Europe late in 1869 and enrolled in the Royal Academy on January 1870. His primary teacher was Wilhelm von Diez, who guided him to appreciate the dark, strongly brushed styles of the Dutch and Spanish Old Masters. However, the stronger influence on his development in Munich was surely his association with Wilhelm Leibl, then the leader of the realist movement in Germany. Duveneck's two years in Munich were extraordinarily successful: he received the Royal Academy's major prizes, was granted free use of a studio and models, and attracted the favorable attention of leading figures in the German artistic community.

Duveneck made his first trip to Venice before returning to America late in 1873. He taught at the Ohio Mechanics Institute in the autumn of 1874. [Cincinnati?] Robert Blum and John Twachtman were among his students. This success [what success? Author deletions have eliminated reference point] was bolstered when a selection of his work was shown in New York.

Late in the summer of 1875 he returned to Europe, accompanied by Twachtman. They traveled in France and the Low Countries, and in 1876 Duveneck returned to Munich. He spent much of the next year in Venice but in 1878 was back in Munich, summering in the Bavarian village of Polling. There he and Frank Currier began a painting class, which continued in Munich. Among his students were Twachtman, Otto Bacher, Joseph DeCamp, Walter McEwen, and Julius Rolshoven. Duveneck had a natural gift for teaching, and his students shared his interest in direct painting with a bravura stroke. In 1879, when at the invitation of Elizabeth Boott he left to teach in Florence, most of his Munich students, who were already known as the "Duveneck Boys," followed.

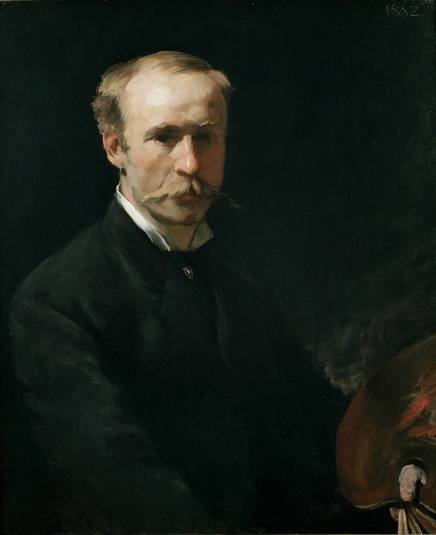

Over the next several years Duveneck worked in Florence, Polling, and especially in Venice. In 1880 he began exploring the etching medium. In 1882 he was briefly back in America. In 1885 he was studying in Paris. The next year, after a long courtship, he and Elizabeth Boott were married. They lived in Florence with her father, a wealthy expatriate Bostonian. Her sudden death just a few days before their second wedding anniversary, wrought a marked change in Duveneck's life and pattern of work.

In 1889, after making arrangements for the future of their infant son and for his wife's tomb in Florence, Duveneck returned permanently to the United States. After a stay in Boston, he settled in his family home in Covington and established a professional association with Cincinnati, largely as a teacher, that was sustained for the remainder of his life. Although he began teaching at the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1890, his immediate major preoccupation was with sculpting a monument to his wife; it was a life-size figure of remarkable somber power. In 1891 he returned to Florence to oversee its installation on her grave. He spent much of the rest of the decade traveling in Europe and in America, interspersed with periods of teaching. In 1898 he made the first of his thereafter yearly summer visits to Gloucester, Massachusetts. In 1900 he joined the faculty of the Cincinnati Art Academy and three years later was made its chairman, a post he held until his death.

Duveneck continued to paint and showed an increasing interest in sculpture. His work was included in major international and national exhibitions but not in the Academy annuals, in which he was represented only in 1877, 1879, and 1888. He was a favored choice for jury member for the art sections in several of the great international expositions. However, during his lifetime he did not attain the preeminent national recognition that might have been his had he not made his base of activity so far from New York.

A sign of the recognition that his work would receive-and a reflection of the profound influence on American art that his teaching had exerted-came late in his life: at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915 a full gallery was devoted to a small retrospective of Duveneck's paintings, etchings, and sculptures. He was awarded a special gold medal in recognition of his achievements.